R. G. Dun & Company and the Business of Information in Gowanus

It was one of the first companies to give its subscribers business information, and helped create the modern business world.

Editor’s note: This story is an update of one that ran in 2015. Read the original here.

R. G. Dun & Company was founded in 1841 as the Mercantile Agency by Brooklyn Heights merchant and financier Lewis Tappan. He established the company as a network of correspondents who would be reputable, reliable and neutral reporters of companies and their credit worthiness.

It was one of the first companies to give its subscribers business information, and helped create the modern business world. In 1849, Tappan turned the company over to his clerk, Benjamin Douglass. He capitalized on the telegraph and other modern means of transportation and information gathering, and was able to greatly expand the company across the country.

He created the profession of credit reporters, who were skilled in interpreting and reporting on financial measures. Four of Douglass’ many reporters went on to have impressive careers as presidents of the United States. They were Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Grover Cleveland and William McKinley.

In 1859, Douglass turned the business over to his brother-in-law, Robert Graham Dun. He changed the name to R. G. Dun & Company, and further expanded the company during the Civil War and beyond, so that by the 20th century, R. G. Dun was one of the most respected national and international credit reporting firms.

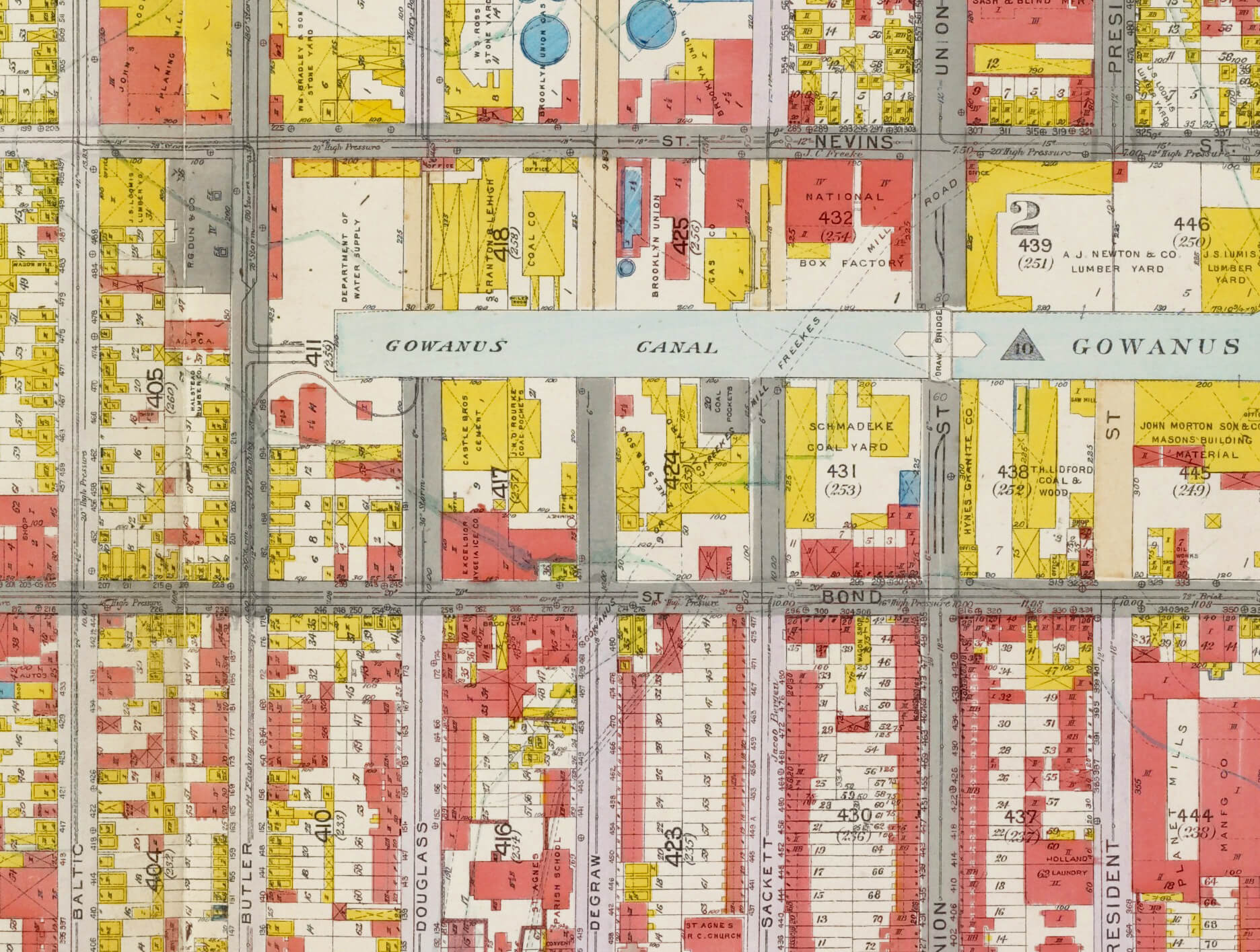

In 1913, R. G. Dun & Company had its offices at 290 Broadway, in Manhattan. But they needed outside room for their printing operations, and so purchased a large empty lot on Nevins and Butler streets in Gowanus that had been used by the Halstead Company as a lumber yard. They hired the venerable firm of Renwick, Aspinwall & Tucker to design a printing factory. The factory was constructed in the new “fireproof” reinforced concrete, and was built so that more floors could be added later, if necessary. Like most buildings of this type, it had banks of large windows running along the two street facing sides, allowing the maximum amount of natural light and air.

The architectural firm was the successor to James Renwick, one of the most important architects in Brooklyn and New York in the mid-19th century. The Renwick in the firm now was William Whetton Renwick, a nephew of James. He joined his uncle’s firm in 1883, when the firm was Renwick, Aspinwall and Russell. When the senior Renwick died in 1895, James Lawrence Aspinwall became the senior partner. Several partners later, they became Renwick, Aspinwall & Tucker. We know next to nothing about Mr. Tucker.

Renwick had inherited the design stylings of the Gothic Revival that had propelled his uncle into the forefront of American architecture. Most of his work for the firm, like the Community House for Grace Church, was in this vein. Aspinwall designed many of their other buildings, most notably the landmarked American Express Building in the Wall Street area. Perhaps both of them had a hand in this factory, which has very, very vague Gothic styling in the form of the top floor windows.

The factory at 255 Butler Street was designed to hold R. G. Dun’s publishing arm. They printed the company’s reports and other publications here. In 1933 R. G. Dun merged with their chief rivals, the John M. Bradstreet Company, forming Dun & Bradstreet, today synonymous with financial reporting and business credit reports.

Dun & Bradstreet eventually sold the building, moving their publishing and headquarters out of state. The factory became home to various kinds of manufacturing over the years. Then that too ended and it was bricked up and abandoned. In 2013, a development group led by Sam Boymelgreen, son of controversial developer Shaya Boymelgreen, purchased a long time lease on the building, intending to turn it into a luxury hotel.

The building is still owned by Nathan and Solmi Accad, who bought it in 2004. The plans for a 162 room hotel never moved forward. In 2015 new plans were filed to convert the former factory into an office complex.

The building is on a list of potential landmarks proposed by the Gowanus Landmarking Coalition. While the Landmarks Preservation Commission recently calendared five of the buildings on the list, the Dun building is not one of them. The building is included in the Gowanus Canal Historic District, which was declared eligible, but not ultimately listed on the National Register.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- LPC Calendars Five Historic Industrial Buildings in Gowanus, Says Public Hearings Coming Soon

- A Gowanus Shelter for the Animals of Brooklyn

- An Industrial Building, the Gowanus Station, Surprises With Terra-Cotta Flourishes

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

Where can I find more historical information about this building? I’m hoping to find floor plans to use for an architecture thesis project

Some possibilities if you are looking for historic floor plans: You may want to hunt through architectural and engineering publications of the period (Architectural Record etc.) to see if plans for the building were published. Your school may have access to the Avery Index to Architectural periodicals which can help with this kind of hunt in addition to a google book hunt. Alternatively, you could make a request for the folder of historic materials from the Brooklyn Department of Buildings to see if the plans are still within the folder. This doesn’t always work, but I have had some luck over the years. Good luck!