Warming Up in Brooklyn: The Art of the Fireplace

Most people love fireplaces. Fires are romantic, nostalgic and memory invoking.

A circa 1880s trade card for the Brooklyn firm Lang & Nau. Image via Brooklyn Museum

Editor’s note: This is an update of a series that ran in 2010. Read the originals here: Part 1 and Part 2.

Most people love fireplaces. Perhaps it’s the primal quality of fire, or the novelty of a heating source of choice rather than necessity. Fires are romantic, nostalgic and memory invoking.

When our homes in Brooklyn were first being built, back in the 1600s, there was no nostalgia. A fireplace was a necessity for heat and cooking.

Early hearths were large to accommodate a variety of cooking jobs, as well as to provide heat for the main room of the house. Federal and Georgian homes often have very formal paneled walls with a large fireplace in the middle.

There was no mantel shelf, but paneled insets perfect for paintings. Pediments often crowned the wall, framing the fireplace.

By the time the 1830s rolled around and our earliest neighborhoods, such as Brooklyn Heights, were being settled, the fireplace and mantel had simplified into a frame with a mantel shelf, a frieze panel below it, and pilaster trim or colonettes, which are small slender columns, to the side.

Trim was used for the first time, and could be classic egg and dart molding, or carved swags, sunbursts or garlands. The mantels were usually pine and were painted. It was also popular to faux paint them to resemble better wood, or marble.

The Greek Revival, Italianate, and some Neo-Grec row houses began to forgo wood for marble. White marble was the most popular, and the richer the house, the more ornate the carving and the larger the fireplace.

The parlors in Greek Revival houses often had large black marble mantlepieces with prominent veins of white or gold, with relatively simple lines, and large pilasters, although white was very popular as well.

Gothic Revival homes tended to have white marble mantles with simple lines in order to accommodate Gothic trefoils, quadrefoils and other ornamentation.

The iron inserts were also decorated with Gothic imagery and shapes. In both styles, lesser rooms could have white or grey marble, slate, or wood.

Starting in the 1840s and by the dawn of the Civil War, central heating began to appear in fine homes, according to the row-house history book “Bricks and Brownstone.” The fireplace was beginning to be seen more as a focal point of a room, from a decorative sense, rather than the source of heat.

Wood and coal furnaces in the cellar could now deliver hot air through ducts and vents throughout the house, sometimes through the vent in the fireplace itself.

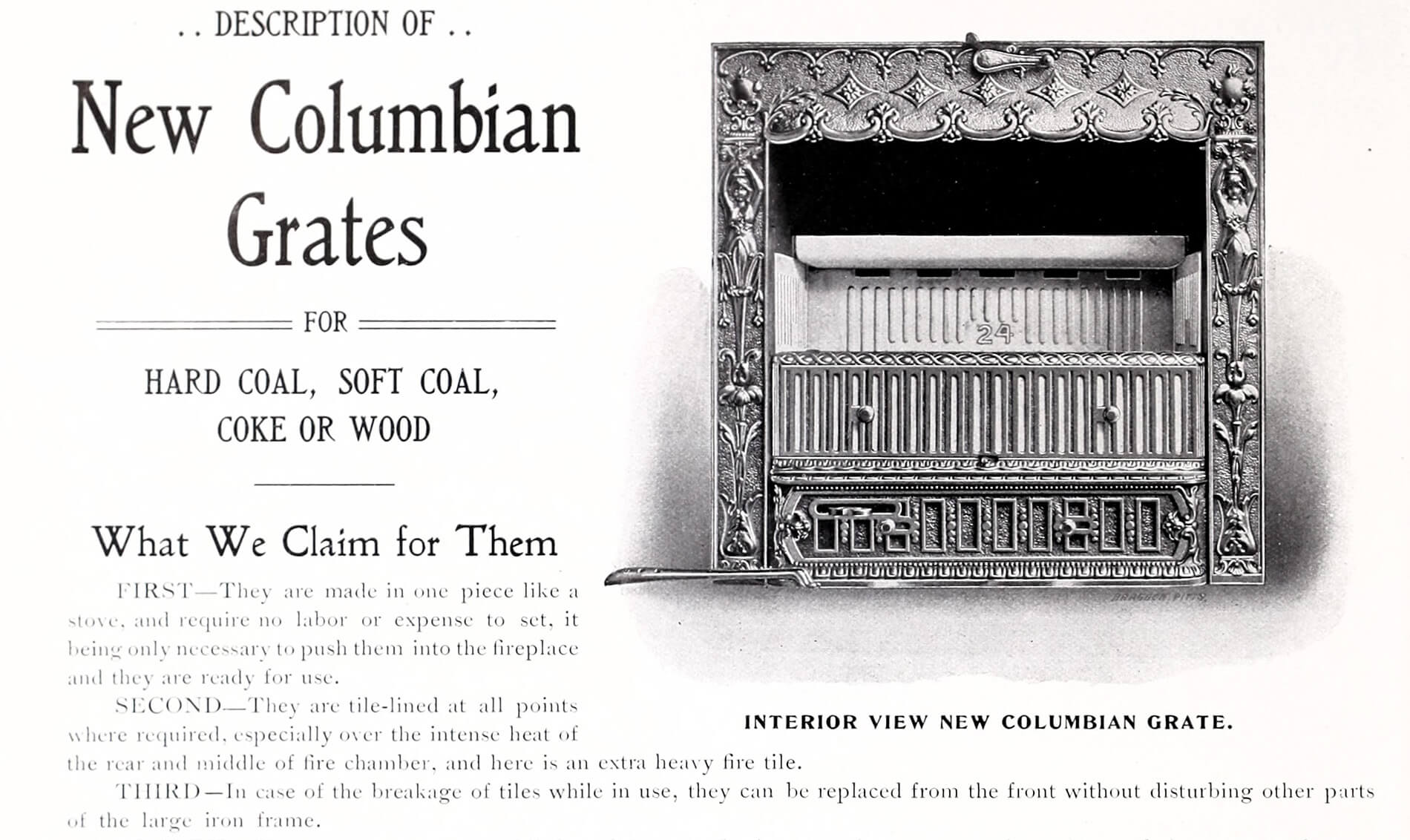

Some fireplaces were still functional, but by this period, coal was the preferred fuel, and a coal firebox was considerably smaller and narrower than a wood box.

Marble was the material of choice, and the mid 19th century was the period of the classic brownstone white marble fireplace with the scalloped mantel shelf, decorative keystone, and arched opening with its iron firebox and screen.

The most expensive homes had pure white marble mantels, often with elaborately carved figures called caryatids, woman’s figures carrying the mantel shelf on their heads.

The rest of the mantel could be carved with floral decoration, and perhaps an exquisitely carved bust for the keystone. Less expensive mantels were made of a lower grade white marble with a lot of grey in it and duller than higher grade marble. Sometimes other colors of marble, such as black, pink or green would be used, sometimes as a decorative insert.

Upper floors or more humble homes might also have slate mantels faux painted to look like marble. Slate was very easy to cut and carve, and cost much less.

Wood mantels faux painted to look like marble were also popular at this time. Often the paint jobs were so good, one couldn’t tell it wasn’t marble.

Regardless of the material, most of the mantelpieces of this time were made in pieces and assembled on site, with a bonding agent such as mortar holding together the various elements and holding the mantel to the wall.

Very few of the marble surrounds were one piece of marble, as the cost for that would be astronomical.

Factories had advanced by this time to the point that each component of the mantelpiece was cut from the larger marble slab by machine and shaped and polished by machine, with only the keystone and fancier decorative elements polished by hand.

A marble mantelpiece could then be affordable in every major room in the house. Another important decorative element in the fireplace, which appears around this time, is the large over-the-mantel mirror.

A separate element from the fireplace, these mirrors were usually gilded or painted gold, and could be oversized to take up three or four feet of space above the mantel, or continue to the ceiling, with an ornate frame.

My first home in Brooklyn, a small 1870s Neo-Grec, in Bed Stuy, had marble mantelpieces. I had five fireplaces in the house.

They all had eight layers of paint on them. Even though I was renting, I couldn’t stand the painted fireplaces and spent a lot of time stripping the mantelpieces.

The ground floor had a very grey/white marble mantelpiece, without much decorative carving. My forced air heat came up through the fireplace, so the iron grate in the center had louvers to adjust the openings, as did all of the fireplaces.

The two fireplaces on the bedroom floor were also the same greyish/white marble, but the two on the parlor floor were a better grade of white marble, and both had reddish/rose colored marble inserts on the side pilasters.

They were all beautiful, and worth every minute to strip, even though I was only renting. The many previous owners had painted over both the marble and the iron grate.

After stripping the marble with chemical stripper, plastic scrapers, toothbrushes and dental tools, I ended up making a poultice of bleach and baking soda to leech out the last of the brown paint residue from the very porous marble. Please don’t EVER paint marble fireplaces.

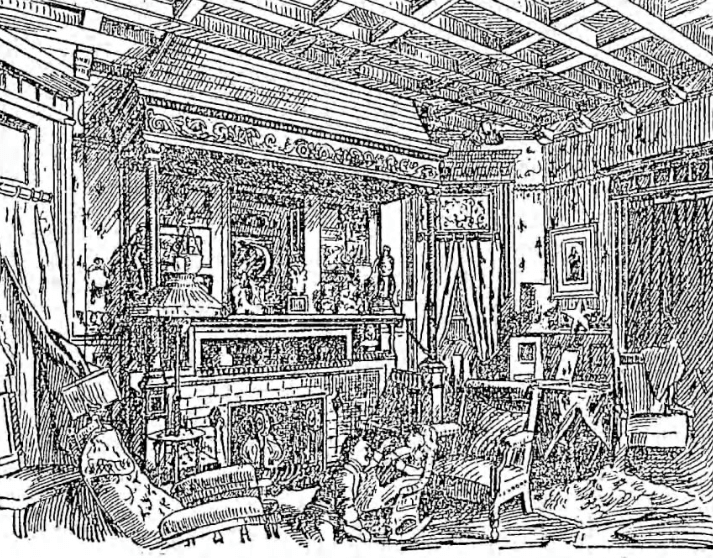

As the Neo-Grec, Romanesque Revival and Queen Anne styles gained popularity in the late 1870s through the 1890s, marble gave way to wood.

This is the age of Eastlake and the Aesthetic Movement, and the age of beautiful and natural woodwork and trim. The fireplace, as the focal point, became the most elaborate and decorated piece in a room.

Gas would replace coal as fuel, with fake logs and flames imitating the wood fire of old. This was pure decoration, at this point, with plumbing, central heating and, by the end of the century, electricity in most homes.

A fireplace helped warm a room, but few townhouse occupants depended on it as their only source of heat. But what decoration they had!

Fine woods, elaborate over-mantels with shelves often rising to the top of tall mirrors, turned wood and carved elements are common during this period.

Unlike earlier fireplace mirrors, the mirrors are now a part of the mantel, not just hanging above it. Carved lions and other animals often bared their teeth on upper and lower shelves, and bright ceramic tiles adorned the fireplace during this period.

In more expensive homes, tiles by Minton and other famous tile companies formed the surround. These tiles usually had floral and animal themes, human portraits, or referred to famous events or tales.

Beautiful tinted glazes gave the fireplace a burst of color, while sometimes the tile even told a story, or immortalized family members or famous people or events.

Hunting scenes were popular, as were blue and white Delft tiles, and classical swags and bouquets. The fireplace was truly a thing of beauty during this period, echoing the Aesthetic and high Victorian mode of surface decoration wherever possible.

As the focal point of the room, the mantel with its shelves and nooks could hold many of the popular decorative objects so loved by the Victorians such as picture frames, vases, statues, figurines and other manner of bric-a-brac.

When the gas was not in use, the mantel shelf could also be finished with a fabric cover, often with fringed edges, tassels, scalloped or dagged edges, with gold couching and embroidery. Remember, for a middle and upper class fascinated with buying the multitude of decorative goods available, more is more.

Just when you think the architects of the day couldn’t do anything more with the classic mantel, having shelved and mirrored and over designed the fireplace into something totally unrecognizable as an enclosed pit for fire, some architects in higher end homes began to play with the fireplaces themselves.

We find the fireplace placed diagonally in corners, back to back in parlors or transformed them into inglenooks, a very popular arrangement for those adhering to Englishman William Morris’ Arts and Crafts philosophies.

Since our row houses often didn’t have room for all of that, a popular nod to the inglenook was the roofed mantel. This was a favorite in Montrose Morris’ decor, as well as Magnus Dahlander and others, and was a precursor of the American Arts and Crafts movement, which was gaining popularity towards the end of the century.

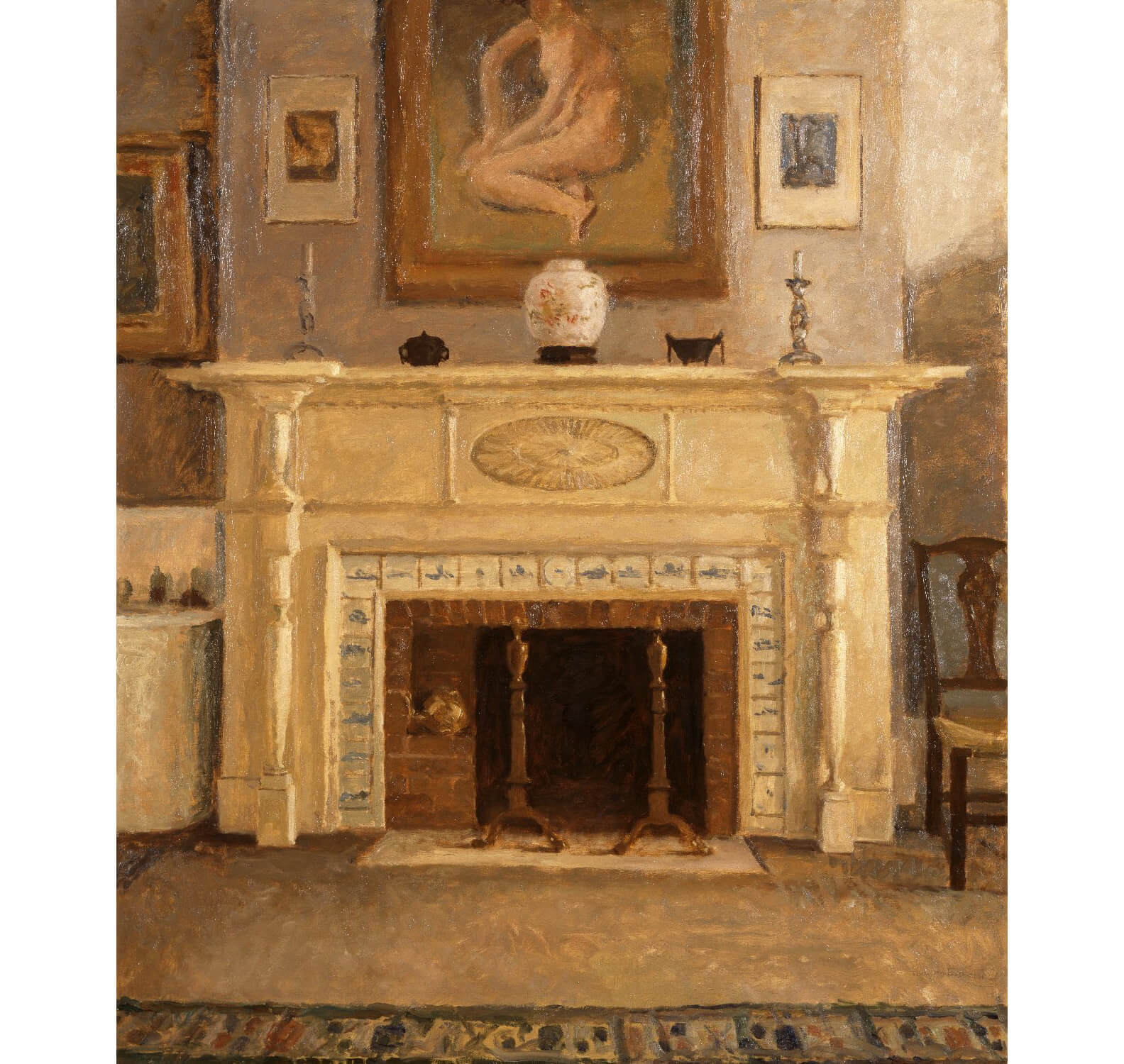

The turn of the century brought changes to the fireplace. The Renaissance Revival style, ushered in by the return to the Classical mode by the White Cities movement begun in the early part of the 1890s, meant the end of the overly carved and ornamented fireplace.

Many Renaissance Revival homes have the beginnings of Colonial Revival interiors, with very classic lines and lots of columns, even on the fireplace mantels.

Axel Hedman’s homes in Prospect Lefferts Gardens, Park Slope and Crown Heights come to mind. Columns are a must for this style, and oak and other woods were used to form all kinds of mantelpieces. Tall columns rose to support the mirror frame, often oval in shape, or shorter, squat columns supported the mantel shelf.

Natural and painted wood were both used. Compo, a sawdust and resin material that could be pressed into molds, was used extensively.

Most of the decorative carved garlands and swags, Classical urns and vines that adorn not only fireplaces, but door frames and other woodwork in houses of this period are actually compo components glued to the wood.

Compo is available today, in the same shapes and patterns, often from the same companies that produced the material 100 years ago.

Tile work became much plainer, with glazed 1 by 4 tiles the norm, covering below the mantel shelf and around the opening of the fireplace.

Patterned tiles are out of fashion, and these tiles are glazed in beautiful shades of the same color, like a deep maroon, Kelly green, or mauve pink. Sometimes a mottled pastel glaze in green and pink was used, as well.

Occasionally, an even smaller half inch by five inch tile shows up on surrounds of this period. These fireplaces are usually gas, usually with a free standing iron basket with ceramic logs that produced flame-like patterns.

The hearth is decorative, and usually has the same tile work on the floor of the fireplace, with a cast iron fire back. Highly decoratively carved cast iron covers are used to cover the opening when the fireplace is not is use.

Today these are highly prized, and expensive to buy in salvage markets.

The Arts and Crafts movement was also happening at this time, and it is interesting to see how the two styles, Arts and Crafts and Colonial Revival, are mixed in Brooklyn homes.

Pure Arts and Crafts lines are found in the two-family Kinkos houses of Crown Heights North and Park Slope, and also in some of Axel Hedman’s houses of the turn of the century, such as in several of his Ocean on the Park houses.

Many homes in Victorian Flatbush have Arts and Crafts interiors, with large 4-by-4-inch tilework in the fireplaces, hand forged hardware, and simple mantelpieces held to the wall with simply shaped brackets.

The Arts and Crafts movement was all about the simpler past, so we find a lot of wood burning fireplaces again. What I find most interesting are the houses that incorporate elements of the Colonial Revival with Arts and Crafts, resulting in an Arts and Crafts tile surround and hardware within a mantel that is more Colonial Revival, or seems to be at first glance.

A Magnus Dahlander home in Crown Heights is a perfect example, with large tiles, classic Craftsman detailing in the surround in an upstairs fireplace, while in the parlor, a classic Colonial Revival fireplace takes pride of place.

As the 20th century progresses, fireplaces began to disappear in New York. Floor and wall space began to be more important to buyers than decorative and unused fireplaces.

Developers who specialized in the large middle and upper middle class apartment buildings of the 1920s and 30s often put their fireplaces not in the apartments but in the lobbies of their buildings, thereby showing class, but not wasting space.

If there was a fireplace in the apartment, it was in the dining room or study rather than in every major room. Apartments for the rich still had fireplaces, but they were amenities that waxed and waned in popularity.

For everyone who loved a fireplace, there would be someone who found them archaic and un-modern. The modernists and builders of Art Deco apartment buildings in all the boroughs did not design fireplaces.

Today, they are undergoing a comeback. For some, the ability to have a roaring fire in the winter is worth any expense. For others, the decorative mantelpieces and the fireplace itself as a decorative element and a period detail are important to the old house experience.

And for some, the opportunity to use the fireplace, whether wood, gas, coal or a stove surround, is a chance to reduce high heating bills and live in simpler times. And some people love the exposed brick, no mantelpiece at all, plain fire box as a minimalist element.

Whatever the look or the reason, the fireplace, and the mantelpiece, are as popular as ever.

Related Stories

- History Underfoot: Flooring in the 19th Century Home

- From Pakistan to Brooklyn: A Quick History of the Bathroom

- From Open Hearths to Open Plan: 350 Telling Years of Kitchen History

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment