Despite Building Boom, Housing in Brooklyn Is Not Getting More Affordable

A startling number of affordable units have monthly rents close to those of market-rate units, and often in the same building.

Construction in Greenpoint. Photo by Susan De Vries

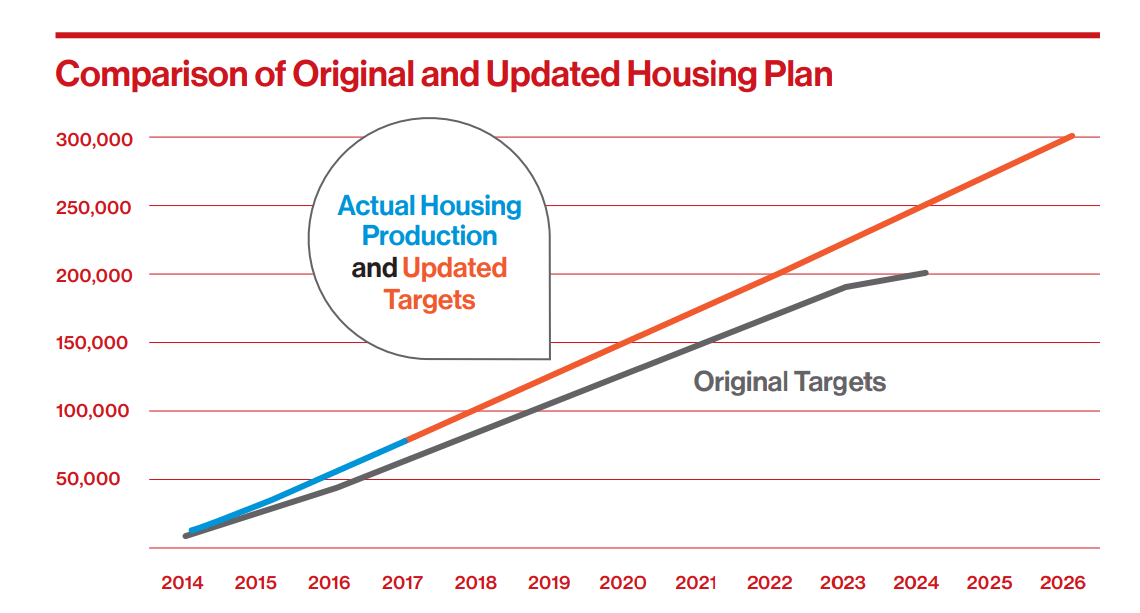

In October 2017, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced his reformed affordable housing strategy. Titled “Housing New York 2.0” (a sequel to the original “Housing New York”), it was meant to be a cause for celebration. His stated plan to build or preserve 200,000 units of affordable housing in 2014 would be achieved by 2022, the city said. So they were expanding on their initial goal, making a commitment to build or preserve 300,000 units by 2026.

This sounds like a success story. The mayor is close to reaching his stated goal, which, in many ways, is a remarkable feat. But in reality, only a small number of those units will help make the city more affordable. In Brooklyn, a quick look at the affordable housing options show that a startling number have monthly rents that are close to the current rents of market-rate units, and often in the same building.

“When the ads [for affordable housing] come out, there is no way for anybody in our neighborhoods to get one of those apartments,” said Jean Folkes, a resident of Flatbush and member of the Flatbush Tenant Coalition. “We don’t see any real affordable housing happening anywhere in Brooklyn.”

Affordability is an urgent issue. According to a report by New York University’s Furman Center published in 2017, the median monthly rents in New York have risen by about $300 since 2000, at the same time that the median income of a household has increased only by $145 per month. More recently, a report in the New York Times found that one out of every 10 children in New York City schools lived in “temporary” housing in the last year.

In other words, the need for affordable housing is real. Some claim it is being addressed: A building boom is reshaping Brooklyn and all of New York City, justified largely, in Brooklyn, by the much-needed affordable housing it will bring. But who benefits?

“This is ridiculous,” wrote one Brownstoner commenter on a recent story about an affordable housing lottery in Bushwick. “These rents are not ‘affordable,’ and if you make enough to qualify, you can afford a market-rate apartment in Bushwick/Ridgewood.”

There are many ways to build affordable housing in New York City. For example, the affordable housing created on city land by agencies and other nonprofits is often 100 percent and aimed at low-income populations; the same with affordable housing built under the Extremely Low & Low-Income Affordability (ELLA) program, which requires that 10 percent of the apartments in a project are set aside for formerly homeless households and an additional 30 percent of the apartments are affordable to what HPD defines as households with “extremely low and very low-incomes.”

But there are other ways as well. Some of the most egregious examples of units that stretch the definition of affordability occur in privately developed buildings that receive or are set to receive the 421a tax exemption. A tax incentive program that was created in 1971 to help promote new development during a housing crisis, 421a has gone through many iterations. The latest, passed by Governor Andrew Cuomo in 2017 — it has now been renamed Affordable New York — allows a percentage of the required affordable units to rent at 130 percent of the area median income.

Calculated annually by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the area median income for the New York City region is currently $93,900 for a three-person family. Which means that at 130 percent of the area median income, a family of three — two parents and a child, for example — must bring in $122,070 a year to qualify for a two-bedroom apartment.

In many communities, this is not feasible. Jose Lopez, Organizing Director for Make The Road, says that membership of the Bushwick-based community organization makes between $18,000 and $35,000 annually. “These are families with the biggest need and they are vastly ignored by new construction projects,” he said. “As a result, more and more of our members are fleeing the city altogether.”

This is not surprising. An affordable studio in the block-long development at 616-626 Bushwick Avenue called The Saint Marks rents for $2,013 a month, according to a lottery listing in July. A market-rate studio in the same complex rents for $2,150, a difference of $137.

Back in April, a lottery launched for 11 affordable units at 867 Dekalb Avenue in Bed Stuy, a few blocks from the busy Myrtle-Broadway intersection. Two of the units were set at 115 percent, five at 125 percent and the final four at 130 percent of the area median income, with rents starting at $2,163 and topping out at $2,716 per month. Market-rate rentals in the same building, which launched the prior month, were often cheaper than their affordable counterparts: one-bedrooms ranged from $2,100 to $2,500, two-bedrooms ranged from $2,290 to $2,865 and three-bedroom units from $2,740 to $3,300.

As of this writing, there are 709 affordable units available in Brooklyn through the lottery system. Of those units, 280 of them are set at an area median income of 130 percent, and 50, all located at the smaller tower that’s part of the controversial Pier 6 development, at 15 Bridge Park Drive in Brooklyn Bridge Park, are set at an area median income of 165 percent (the development is not part of any affordability program).

The mayor’s request for affordable housing on Pier 6 sparked a series of lawsuits from local residents over the nature and need for more housing in the park. The mayor’s vision ultimately prevailed, resulting in the building of an additional and affordable tower that does not contribute to the income of the park and is reserved for individuals and families earning between $100,000 and $200,000 a year.

Of the 100 units of affordable housing now available at Pier 6, only 25 are set at an area median income of 80 percent, with rents ranging from $1,394 to $2,075 a month. The highest affordable rents are set at 165 percent of the area median income, with a studio going for $2,947 a month, a one-bedroom for $3,147 and a three-bedroom apartment going for $4,380 a month.

“The way it’s played out hasn’t been positive,” said Councilmember Antonio Reynoso of 421a’s implementation in gentrifying communities. He added that Mandatory Inclusionary Housing, a program initiated by de Blasio in 2016 that requires developers who benefit from an upzoning to set aside a percentage of affordable units, with requirements that in its different options are all lower than 130 percent of the area median income, has been more beneficial than 421a.

Although, even here there are still problems: Because the affordability options under 421a almost match some of the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing options, developers can “double-dip,” meaning they get the benefit of a 35-year tax abatement — an extension of the previous 25 years required by 421a prior to 2017 — without having to change much from what they are already required to set aside via Mandatory Inclusionary Housing.

“It is quite absurd,” Lopez said.

Apartments built under the 421a program have benefits, such as their mandate to abide by the rent stabilization laws during the period. But in recent conversations with residents, local activists and city politicians, many said they feel the program needs to be drastically revised, and new and better ways to build affordable housing need to be developed.

“Our affordable housing crisis hits hard at every income level, from those facing extreme poverty to middle-class families made up of hard-working civil servants like teachers and firefighters,” said Borough President Eric Adams in a statement provided to Brownstoner. “The existing tax incentive programs are simply not enough to deal with the depth and breadth of this crisis.

“We need to be creating more affordable housing, at every income band, and we need to be doing it faster. We need to invest time and energy in establishing new initiatives that protect our existing affordable housing stock, including through technological advances that help hold bad-acting landlords accountable for destabilizing families and raising rents, and we need to explore how we can reinvigorate existing programs like Mitchell-Lama that have been so impactful for so many families.”

Reynoso thinks there is a brighter future. “When 421a gets renegotiated, we’re going to be in a different time in New York,” he says. “It’s going to be a more progressive city, and I can see it getting a lot more aggressive, a lot more beneficial to the communities that are being affected.”

But for those who most need affordable housing now, the options are grim. “It’s not really for us,” Folkes says about the bulk of affordable housing. “People who are working at McDonald’s, people working at Macy’s, they don’t make that kind of money. People who clean people’s homes, they need somewhere to live too.”

Related Stories

- Bushwick Community Plan Calls for More Affordability and Historic Districts

- Affordable Housing Lottery Opens for 30 Pricey Units in Converted Bushwick Church Complex

- Affordable Lottery Opens for 100 Units at Controversial Pier 6 Complex, Starting at $1,394

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment