Decorator William Payne and His Collection of Colonial-Era Lefferts Houses

Victorian decorator William Payne was an early enthusiast of New York’s Colonial past, whose efforts were well documented in photographs.

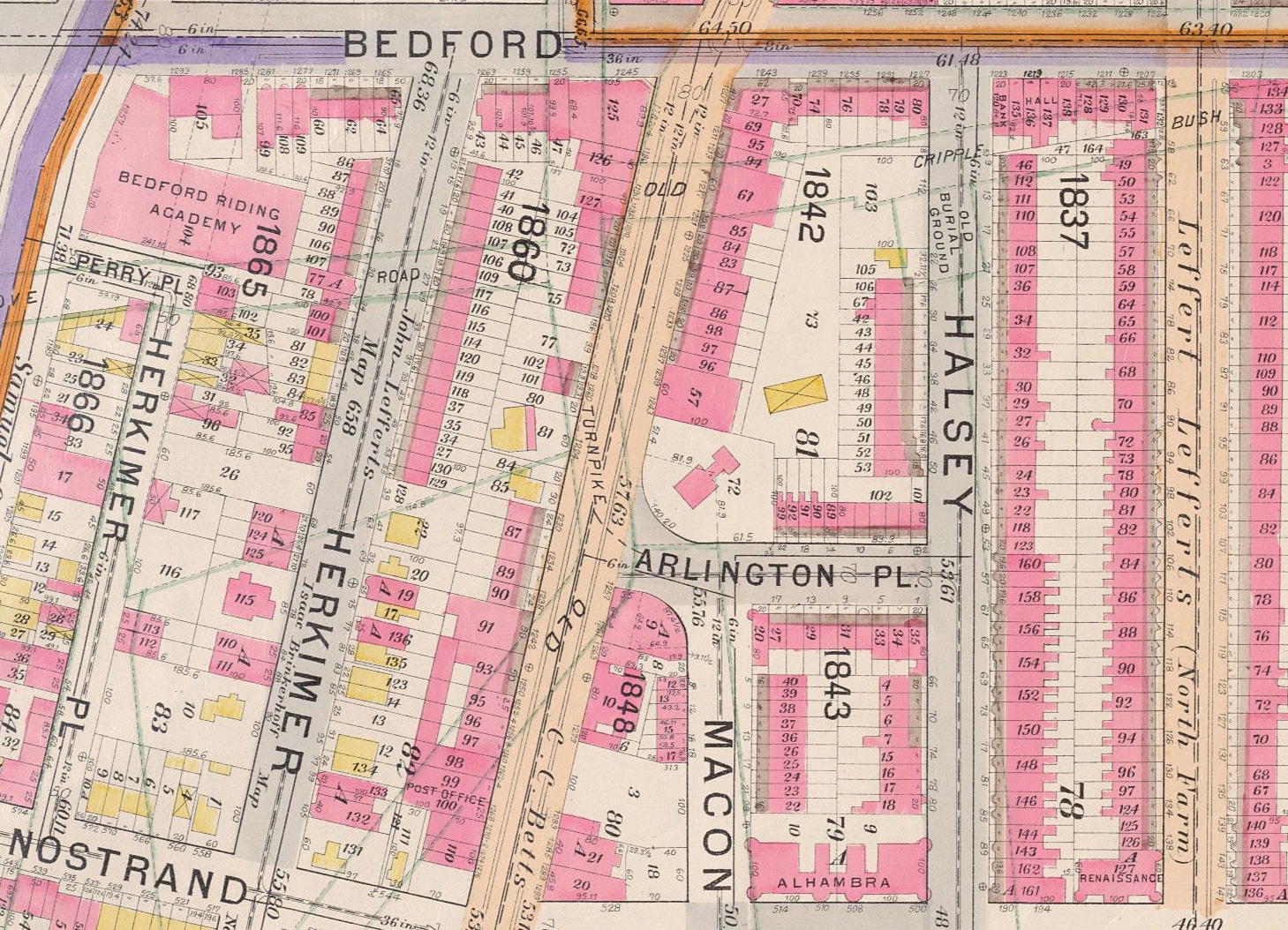

William Payne purchased a Lefferts family home on Halsey Street and leased another on Fulton Street. Portrait of William Payne via Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Map from 1880 by G.W. Bromley & Co. via New York Public Library

Explorer Henry Hudson landed on Coney Island in 1609 and reported back to his Dutch employers that he sailed up a wide river and saw a beautiful and bountiful land. The Dutch West India Company traded with the various Native Americans for New Amsterdam over the next few years and by the mid-1600s had “purchased” most of the land making up Brooklyn from the indigenous Lenape people. The company then began giving sizable land grants to settlers, effectively dividing up western Long Island into large farms, which were further subdivided among tenants. One of these settlers was Leffert Pietersen Van Haughwout, who arrived in New Amsterdam in 1660 to farm on a large expanse of land in Flatbush.

In 1700, he bought land from another farmer named Thomas Lambertse in the nearby town of Bedford Corners. He moved members of his family there, acquiring in the purchase Lambertse’s tavern and a lot of land. The large family would be split between the Flatbush and Bedford branches for the next few centuries.

Many European family names are derived from the area from which the person came or were taken from the first name of the family patriarch. Leffert Pietersen was from the Dutch town of Hoogwoud (the family name “Haughwout” was a variation on the spelling), but here in America, the family name became “Lefferts.” One of his 10 sons, Jacob Lefferts, settled happily in Bedford and through trade, outright purchases, and marriage soon had quite a large estate, worked by enslaved people and small tenant farmers.

Subsequent generations continued to grow their holdings and married into prominent families such as the Remsens, Suydams, Vanderbilts, and Lotts. By the beginning of the 19th century, the Lefferts family owned most of Wards 8 and 9, which today make up modern Bedford Stuyvesant and Crown Heights North.

The family seat was in the area bordered by today’s Bedford Avenue, Atlantic Avenue, Hancock Street, and Nostrand Avenue. There Jacob Lefferts built his home in the village of Bedford on what is now Arlington Place and Fulton Street. The old Clove Road passed in front of his house, which explains the dwelling’s odd orientation to the later streets. Other siblings and family members built or lived in houses within blocks of this house, creating a Lefferts compound in the center of the village. One house was just across the street on Fulton, while another was near the family cemetery near Bedford Avenue and Halsey Street, and yet another one on nearby Herkimer Street.

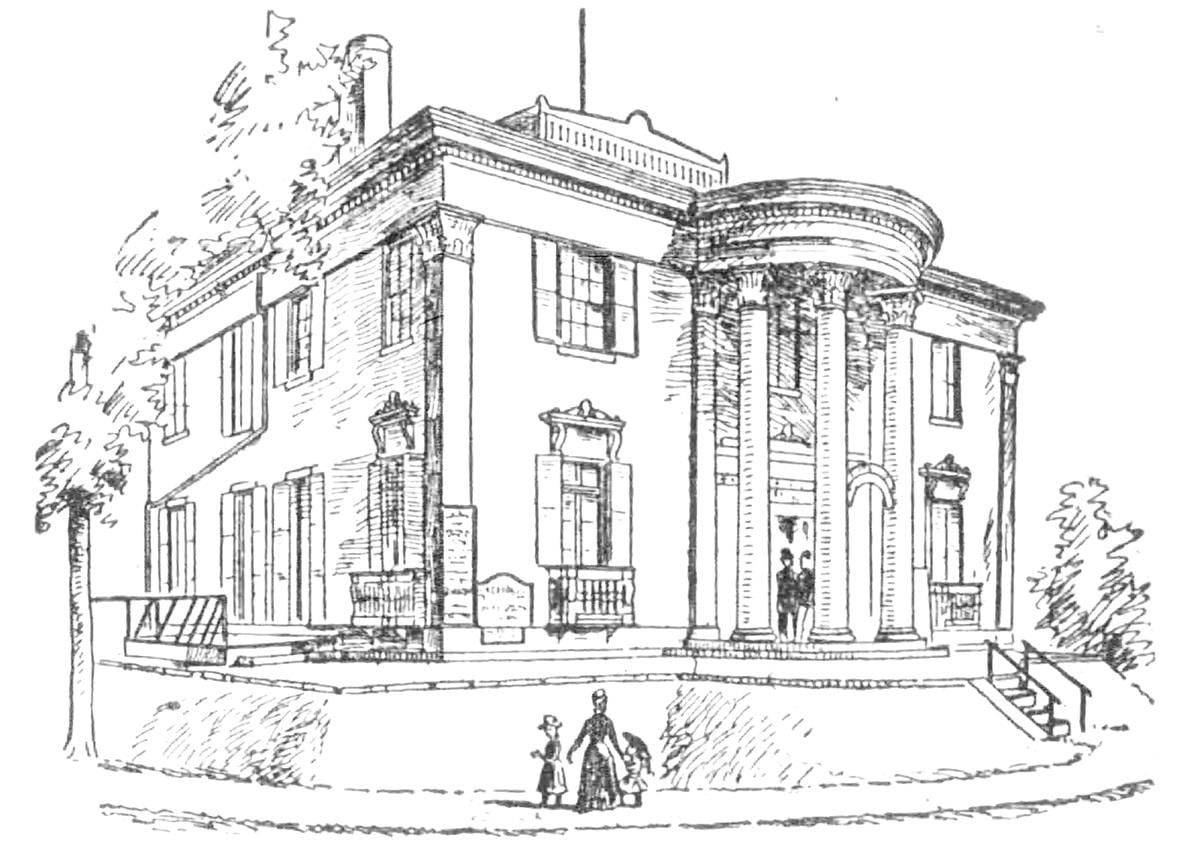

In 1834 the high lord of the manor was now lawyer Lefferts Lefferts Jr. He became Kings County’s first judge and was known by all for the rest of his life as Judge Lefferts. His uncle replaced the old family homestead with a much larger and fancier new mansion. It curved around the corner of Arlington and Fulton and was a grand villa with a huge columned portico and a commanding presence.

The grounds around it were quite large, taking up much of the block behind it. The house itself was said to have solid silver door knobs and huge fireplaces that a man could walk into. Judge Lefferts died in 1847, leaving the immense estate to his only daughter, Dorthea Lefferts Brevoort. By 1854, she and other relatives began selling large parcels of land for development. She already had a fine house nearby with husband Carson Brevoort and did not choose to live in this mansion.

Meanwhile, across the ocean in London, a 38-year-old Englishman named William Payne was building a fine career as an interior decorator. He was well known for his decor for public and private events held at the famous Crystal Palace. His reputation increased after arranging the drapery and funeral trappings for the Duke of Wellington’s funeral in 1852. In 1857 he decided to seek his fortune in America and after a year in the States, he settled in the Fort Greene section, buying a house near the corner of Fulton and South Portland streets. He sailed back to London and brought his wife, Elizabeth, and children over. Their new life in America was on its way.

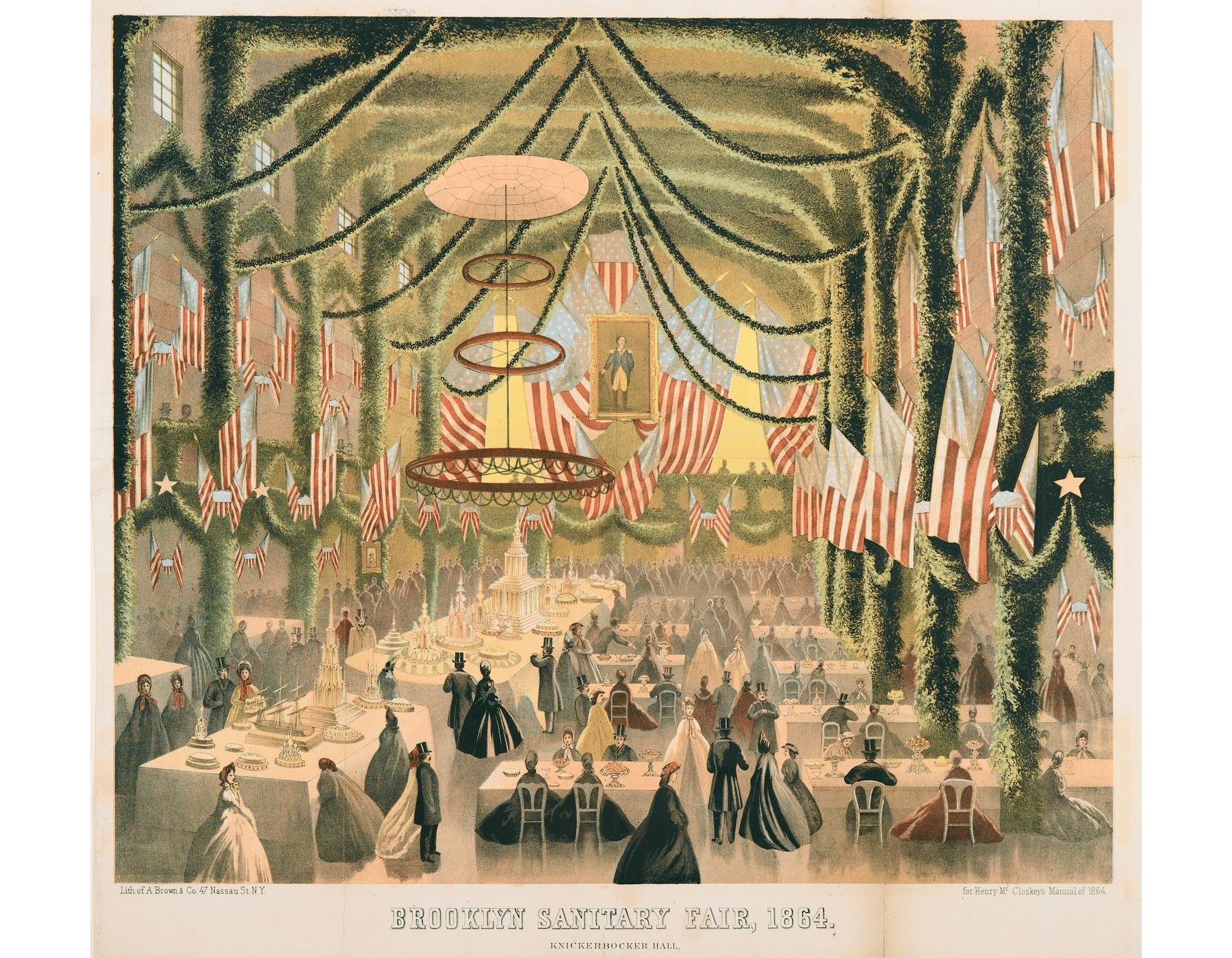

Payne made his first big splash in Brooklyn in 1864, designing the decor for the first Sanitary Fair held at the Brooklyn Academy of Music and adjoining buildings on Montague Street. The event was a fundraiser, with money raised buying medicine, bandages, and medical equipment for the Union Army towards the end of the Civil War. His reputation and business took off after that, enabling him to buy a property from Dorthea Lefferts Brevoort in 1867.

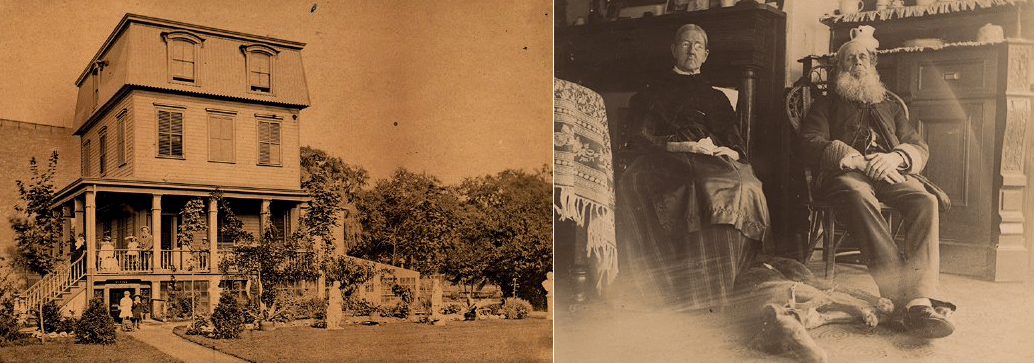

The house he purchased was one of the original Lefferts homesteads on Halsey Street, the one near the family cemetery. It was built when Bedford was still fields and farms. Payne later said that when he visited his new property there were only four or five houses in the neighborhood and the house was situated in the middle of a cornfield with land all around. At the time, the house faced Bedford Avenue, which was still a country lane lined with apple and cherry trees. On the property was a smokehouse said to be the oldest building in Brooklyn.

This land included everything from Fulton Street to Halsey Street and from Bedford to Nostrand. Payne later told reporters that he harvested hay on the site of Girls High School on Nostrand Avenue. He made improvements to the property, which became famous in the neighborhood for its many apple and pear trees and berry bushes, all of which yielded bushels of fruit. One of his pear trees was known to grow pears that weighed over a pound each.

The Payne family lived in the old farm house for over 35 years. In a stroke of rare fortune, William Payne’s home was well documented in photographs. The collection of more than a dozen photographs from 1860 to 1895 now belongs to the Center for Brooklyn History. It includes photos of the property, whose address eventually became 22 Halsey Street. There are also photos of the interior of the house, including one of Payne and his wife in their parlor.

Thanks to those photos, we can see that William made major changes to the house over the years. He reoriented it from Bedford Avenue to face Halsey Street, thinking correctly that Halsey would remain residential while Bedford would be a much busier mixed-use commercial street. He added a third story with a mansard roof, a wraparound porch, an extension on the back, and wings on the side, often using reclaimed elements from houses that were rapidly being replaced with brownstone rows.

His property included the adjacent lot where he had a small barn and a formal garden space with columns and a fountain. His front yard was quite spacious as well, with fruit trees, crops to the left, and room for a croquet court. He also built a greenhouse in the backyard with a pergola above it. Over the years he sold most of his adjoining land to developers at a good price as Bedford continued to develop as a middle and upper-middle class neighborhood.

As time passed, William Payne continued his decorating career, his carpet cleaning company, and gentleman farming while also cultivating his interest in history, especially that of the Bedford branch of the Lefferts family. He was, after all, living in one of their original homesteads. One account of his life stated that he was a friend of Lefferts family members. He was known as an avid collector of artifacts, art, and furniture from the Colonial era, and prized those pieces that once belonged to the Lefferts estate.

He would soon go on to lease another Lefferts property, Judge Lefferts’ grand manor on Arlington Place. The house had several owners before Payne, but no one had lived there for years. Payne rented the building for use as a storage space for his collections and as a business venue. The house was filled with original furnishings and interior details, artwork, and decorative items. The grounds included a stable and other outbuildings also full of interesting artifacts. For a man who loved both antiques and history, possessing the manor was a dream come true. He intended to make the most of it.

Over the years, much was written in local papers about both 22 Halsey and the Arlington Place manor house. A lot of it is contradictory. The Revolutionary War features prominently in the stories. When the British occupied Brooklyn for the length of the war, the Lefferts manor, the finest in Bedford, became both quarters and headquarters for Major John Andre, head of the invading forces. His officers occupied the homes of other prominent citizens, while the common British and Hessian soldiers bivouacked in rude makeshift trench cabins and lean-tos down the length of Franklin Avenue.

Major Andre did not stay in this house, unless he spent a lot of time in the back of the house and the kitchen, which is unlikely. That house, the original Lefferts manor house, was a classic Dutch gambrel roofed structure with added wings. In 1836, Barent Lefferts used the original house as a rear addition to the new Greek Revival main body of the house. But reporters claimed that the more recent structure was indeed the famous pre-Revolutionary War house.

A careful examination of the architecture and contemporary writings would belie that idea. Those who had been in the house and wrote about it could tell where the old and new were joined, as the older house had lower ceilings and other period-related features that the front did not have. A narrow hallway joined the two buildings, which were also not level with each other and required a short set of stairs.

The front wing of the house is much more indicative of the Greek Revival architecture of the 1830s, with the columned portico, the corner pilasters and capitals, and floor to ceiling parlor floor windows. By the end of the century, it too was “old,” but not that old. Up until the Lefferts abandoned the home, the older wing was used only by servants and held the kitchen.

Prior to Payne leasing the mansion, it was home to a girls’ school until 1869. Two years later, it was advertised as a county retreat for rent. Payne took over around 1876, when he advertised the location as a storage facility for items such as pianos, carpets, and other large valuables. He also allowed an exercise club to use the large parlor for classes. As an antiquarian of some note, he began to collect as many of the original Lefferts family artifacts as he could.

Payne opened the house and grounds up to visitors and reporters in 1891 on the 25th anniversary of his marriage to Lizzie McKensey. The day before the event, Payne gave a Brooklyn Times Union reporter a guided tour of the house. “The quaint old building, which standing apparently deserted with closed blinds in the centre of an immense plot of ground, in plain view of one of the city’s greatest thoroughfares, challenges the curiosity of passers-by,” the reporter wrote. “Within the dust covered portals of the old mansion, I stood stock still in the hallway and surveyed the surroundings with astonishment.”

The house was in good condition but looked like a dusty time capsule. The reporter noted that the coffered ceilings were oak, with brass chandeliers. The grand entry hallway was spacious, with a stairway made of red Spanish mahogany. Battle axes, swords, muskets, and other military arms were on the walls or stored in corners. A 16th century sideboard said to have been brought to America by Leffert Pietersen himself held pride of place in another room. Carved chests, wooden chests, and English spinning wheels were found in different rooms along with other furnishings.

In the carriage house they found the Mrs. Rem Lefferts’ family coach, which she used to make her formal calls and visits. She died 30 years before. The coach was square with plate glass sides and lined with white satin, now discolored by age. An antique sleigh was also found in the building. They also found a headstone from the Lefferts family graveyard, which had been removed when Halsey Street was cut and paved.

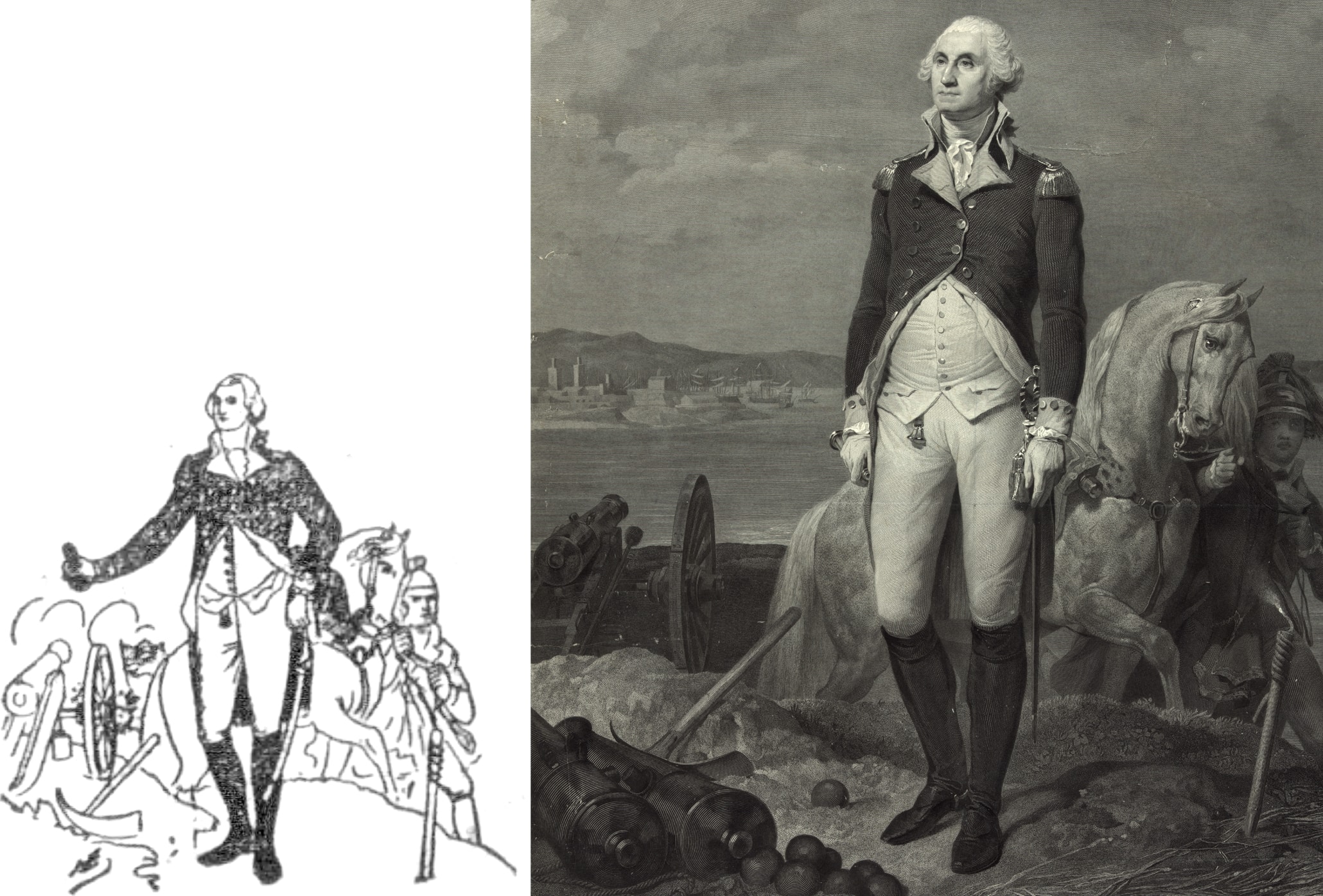

The most valuable item in the house was a large full-sized, full-body portrait of George Washington, which was originally placed in the entry hallway. It was 10 feet tall and 8 feet wide, and portrayed Washington in full military dress standing in a battlefield with cannon at his side and an aide holding his horse at the ready. Payne said the painting was by Gilbert Stuart, who also painted the famous portrait of Washington that is his official image. At the time, this portrait was said to be worth over $10,000, which would be more than $3 million today. Payne used it in his 1864 Sanitary Fair, where it was a great hit. Many museums and private collectors wanted the painting, but Payne would not sell.

Was this huge painting really by Stuart, and what happened to it? There are a great many contemporary paintings of the first president, half of which depict him in his uniform during battle. A similar painting by artist John Trumbull, painted in 1792, depicts Washington in the exact same pose, down to the stance, uniform, and the object in his right hand, but has a completely different background. That painting, which is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is also much, much smaller. Trumbull’s portrait also has a different face than the Lefferts painting.

It is very possible that the Lefferts painting was a copy and adaptation of both the Stuart painting (the face) and the Trumbull painting (the rest of his body and the background theme), with a slightly different background. Dorthea and other Lefferts family members may have known this, explaining why they left such a potentially valuable painting behind, or why they didn’t donate it to a museum or other institution. The location of the painting is now unknown.

Brooklyn at the turn of the 20th century was in a constant state of change. New transportation modes were making all of Brooklyn more accessible. Neighborhoods were being built out to capacity, as new neighborhoods were being created. The rumors and then the actuality of Brooklyn becoming a lesser borough of New York City gave many reporters and Brooklynites a newfound sense of history and nostalgia. Many articles about Brooklyn’s early history, the founding families, their vanishing homes, and the big changes taking place in Brooklyn inspired writers to head to Bedford to the Lefferts compound.

The announcement that the Arlington Place mansion was slated to be torn down first appeared in the Brooklyn papers in 1895. All of a sudden, everyone was interested in the old vacant mansion. By that time, Payne was no longer using the house for storage and as an event space and was planning to vacate at the end of his lease in a few months. The roof was leaking and the house was in disrepair. The current owner, a Mrs. Smith, refused to have the repairs done as she intended to sell it for teardown as soon as she could.

Payne took reporters on their final tours before quitting the house. Many of the valuables were removed for sale. The new owner of the property, a builder named John Moran, brought workmen in to demolish the house piece by piece. He intended to salvage the floors, mantels, and any other valuable parts of the house. In the process, the workmen uncovered flint arrowheads and 17th century gold coins in the original part of the house.

Reporters continued to cover the story, bemoaning the loss of this historic home and recounting its history. But there was no effort to save it, not this house nor any other historic homes that dated back to the early days of Brooklyn. If they stood in the path of “progress,” well, that was too bad. It would not be the only Bedford Lefferts house to be destroyed. Workmen completed the demolition of the manor two years later. The large empty lot was slated for residential and commercial development. It remained an empty fenced-in lot until several years after that, when a group of one- and two-story taxpayer buildings were erected on the site. Those buildings remain.

William Payne died of heart disease at the age of 80 in 1899. The papers referred to him as one of the oldest men in Brooklyn. The earlier death of his only son several years before dealt a blow to him from which he never really recovered. He retired from his businesses and spent his final years investigating and collecting things from his neighborhood’s Colonial past. He left behind his widow and five daughters. His funeral took place at 22 Halsey.

In 1905, the newspapers announced that Payne’s old home at 22 Halsey Street was also slated for demolition. The original part of that house also dated to Colonial years. Once again reporters recounted the history of the Lefferts family and early Bedford life, as well as the life and career of William Payne. They also bemoaned the loss of this historic building, around which so much of important Brooklyn history took place. But it came down, nonetheless. An eight-family flats building replaced it. The lesser-known Lefferts house on Herkimer Street had already been torn down.

The last house was the Rem Lefferts house on Fulton Street, within sight of the old manor. It was an antiques store for many years, independent of Mr. Payne, and had tenants. Stories and photographs filled local papers in 1909, again telling the history of Colonial Bedford and the Lefferts family. This building, probably the best preserved of them all, was torn down as well. Commercial buildings replaced it. It would, as the papers put it, “give way to the march of progress.”

Not everyone was happy about the loss of Brooklyn’s early history. In 1909, after observing the destruction of the Rem Lefferts house, an editor writing in a local paper called The Chat said, “The tearing down of another landmark only goes to show what to expect in the future. There will come a time when, like New York, Brooklyn will have stopped boasting of anything artistic and the one aim will be to get as near the skies in building as possible. It will no longer be the city of homes.”

The man was a prophet.

Related Stories

- Past and Present: The Other Lefferts House on Fulton Street

- The Pope’s Mr. Pope: The Rise and Fall of the Pope Family Mansion on Bushwick Avenue

- Our Beautiful Brooklyn Blocks

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

This was a great article thank you!

Will

This was great. When I discovered Payne it was like finding a gold nugget of the Bedford Stuyvesant history if he could only see what soulless buildings are on his old lot today.