'I Only Do Big Things': Woman, Architect, and Brooklynite Fay Kellogg

Although she designed many smaller structures during her career, Kellogg lived for the big projects, not afraid to go where no woman was allowed to go before.

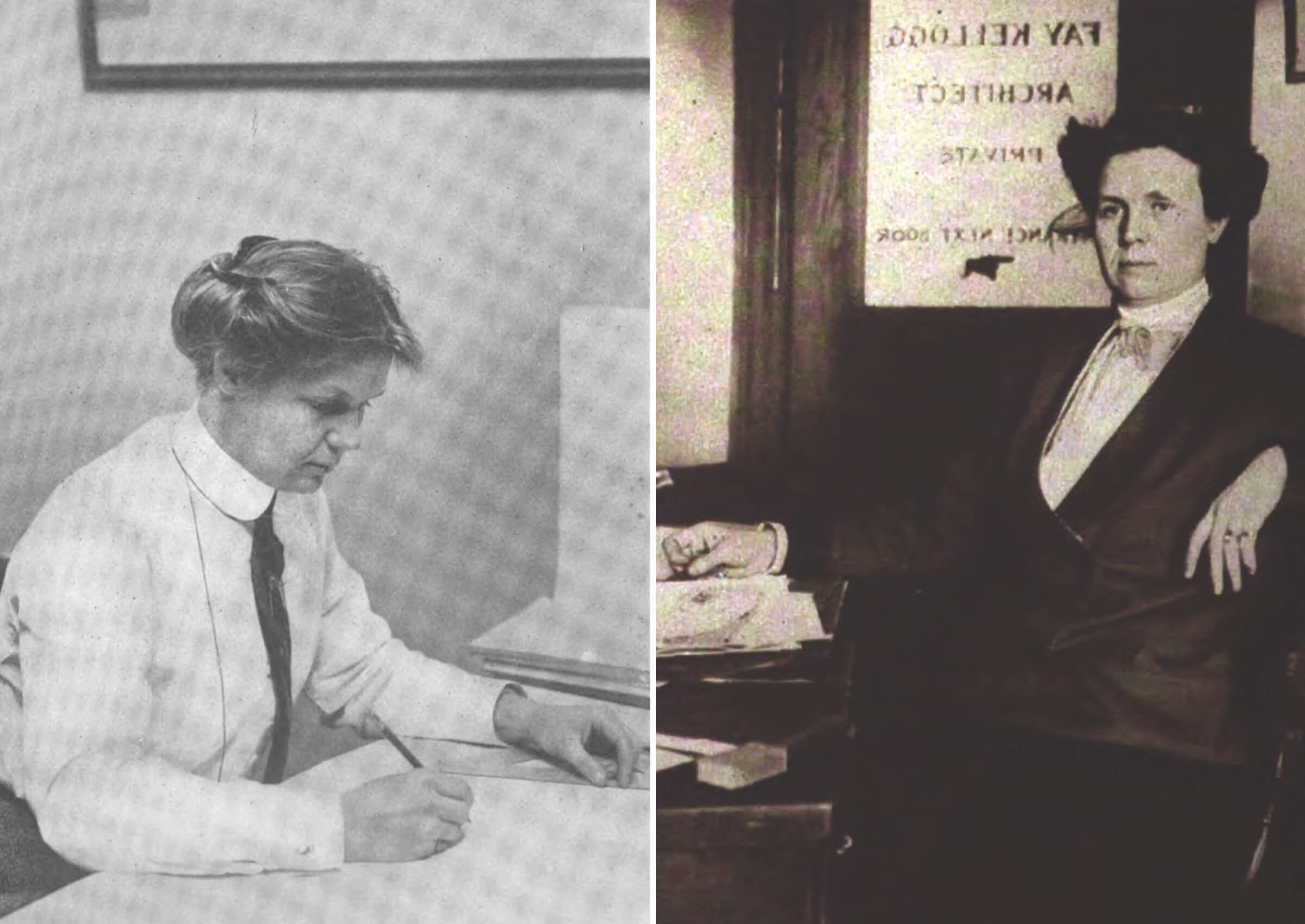

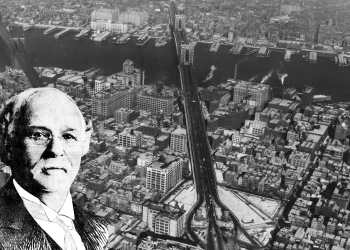

Fay Kellogg in a portrait published in 1914. Photo via “Munsey’s Magazine“

For centuries, Western women have been held up as the sacred keepers of the hearth and home. By the time we get to the late 18th and 19th centuries, a middle- to upper-class woman in America was judged by how she managed her household, or how well she instructed her female servants to do so. After the Civil War, mass production enabled the growing middle classes to have more and more consumer goods for the home. Along with them came the popular style experts advising women on interior design and decor, new trends in home goods, and products galore.

Yet for all the emphasis on a woman’s management of an attractive and well-run home, it was unseemly, and in many cases forbidden, for a woman to design or oversee the building of that home or any other kind of building. The field of architecture was meant to be the realm of men and men alone. Female participation was not needed and was certainly not wanted. How could a woman, especially a well-bred female, possibly learn the mathematics and engineering skills necessary to design a building? How could she work daily with unlettered and lower-class construction workers? It was preposterous!

There always must be the “firsts,” those who defy convention and setbacks, and succeed in opening new worlds for women in careers that were once closed to them. In the late 19th century, as Brooklyn was growing block by block, there were a few women who became row house developers and were the architects of record in many cases. They usually had to change their names, or go by their initials, or be fronted by their husbands. Some of their stories are here.

One woman set out to be an architect in her own right, receiving the same or better education as her male counterparts. She worked in major architecture firms and eventually established her own practice, not hiding her gender or abilities. She became the country’s first well-known female architect. She proved that a woman could design any kind of building and walk up and down a high-rise construction site with the best of them. She was Brooklyn’s own Fay Kellog.

Kellogg was born to Albert and Julia Kellogg on May 13, 1871, in Milton, PA. Her father spent his entire career in machine sales and made a decent living. The family moved to Brooklyn in 1881, when she was 10 years old, and Kellogg was a student at P.S. 15 in Red Hook. Kellogg was the third oldest in a household of six children, with three sisters and two brothers. She was petite and athletic, and in the course of her life enjoyed fencing, boxing, wrestling, equestrian activities, baseball and golf.

Sometime between 1892 and 1894, the family purchased 295 McDonough Street in Stuyvesant Heights. This would be the house she always considered “home,” although she also owned a much-loved farm on Long Island after she became successful.

She grew up at an auspicious time at the end of the 19th century, when it wasn’t quite as shocking for a young woman to want a career. She loved art, drawing and building things, but decided that she wanted to be a doctor. She lived with an aunt while she attended Columbian College in Washington, D.C., now George Washington University. Interviewed in 1907 by the New York Times, Kellogg declared she was “doing famously” at college, when her father paid her a visit. He was concerned that the journey to become a doctor was too long and arduous, and he asked her to give it up.

He told her that if she abandoned medicine, he would pay for her tuition in a drawing school. “After shedding copious tears and bewailing my fate, I reluctantly consented,” she told the reporter. Albert told her that he wanted her to study architectural drawing and draftsmanship. Kellogg’s tears quickly dried up, as she realized that that is what she really wanted to study. Her father knew her well. She had always been handy with tools and beat her brothers in contests using hammers and saws. “It was always my ambition to be able to build my own house which I could call my own,” she said.

A first job.

Kellogg studied with a German tutor for two years. He taught her a German curriculum of architectural drawing and mathematics, a strenuous and rigorous course of study. From there she enrolled in the architecture program at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn between 1891 and ‘92. Following Pratt, she struggled for an entire year trying to find a firm that would employ her.

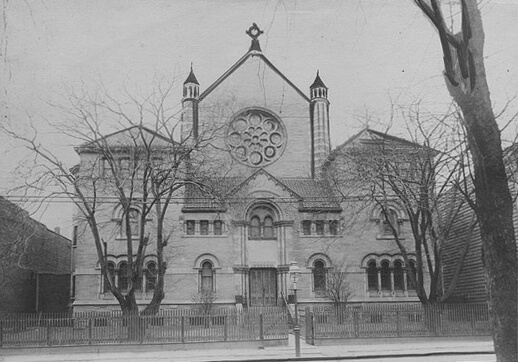

In 1894, she joined the firm of German-American architect Rudolphe L. Daus, one of Brooklyn’s most talented and important architects of the late 19th and early 20th century. He is best remembered for the large civic, religious, and commercial buildings he designed in both Brooklyn and Manhattan. While Kellogg was in his employ, she worked with him on his plans for the 13th Regiment Armory, a commission contest he won in 1890.

The new armory was built in Stuyvesant Heights, on the corner of Sumner Avenue, now Marcus Garvey Blvd, spanning the block between Jefferson and Putnam avenues. It is a huge building, which was built to function not only as a National Guard unit’s home, but also as a valuable community asset. As the first project for a budding architect, the armory would show Kellogg the best and worst of the profession she wished to enter.

The French-German Daus and the colonel of the regiment hated each other, making every design decision fraught with rancor and disagreement. The commander never got over the fact that his preferred architect didn’t win the commission. Because of their lack of a working relationship, the designs had to be modified over and over as the colonel was never satisfied. Construction began in 1892 and was completed in 1894.

The only architect that would hire her, Daus paid her $5 a week. She was grateful that he was willing to take a chance with her. We will never know the extent of Fay’s involvement with the project, or if she had to deal directly with the client. She proudly spoke of it later, and the latest Wikipedia entry in 2023 gives both Daus and Kellogg equal billing as architects. This deserves more study.

She was also Daus’ assistant in the design of the Monastery of the Precious Blood, a project he began working on around the same time as the armory. The cloistered monastery was not all that far from the armory. This project was championed by Daus’ wife, Louise, who helped raise funds and support for this order of cloistered nuns. Kellogg also mentioned this project in later interviews, including the 1907 Times interview. The paper misspelled Daus’ name, calling him Rudolph L. Davis, which no doubt irked the very proud architect greatly. Unfortunately, some more recent articles about Kellogg also misspell his name.

Kellogg left Daus’ employ and worked with the firm of Carrère and Hastings for a year. They were one of NYC’s most important and influential architectural firms, best known as the designers of the Main Branch of the New York Public Library and other important civic buildings across the country.

Demanding further education.

Daus, Carrère and Hastings were all graduates of the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, considered the finest school of the arts in the world. By the end of the 19th century, the school inspired an architectural style called Beaux-Arts, a grand and impressive Classically designed style of architecture, of which these three were masters. They inspired Kellogg to travel to France to further her studies there.

But the École did not admit women. Only one architectural atelier associated with the school accepted women, so Kellogg studied there, with Marcel Perouse de Monclos, a well-regarded architect with an American wife and a modern attitude. She received the same education and worked on the same projects as the men in the studio. But she was not allowed to sit for the exams that would admit her to the École.

While there, she met two other American women, Katharine Budd and Julia Morgan, who were also pupils at the atelier. Kellogg was not prepared to be shut out of Beaux-Arts and lobbied tirelessly to the American Ambassador and the president of the school for it to open its doors to women. Thanks in great part to her efforts, the French government finally allowed women to compete for entry in the sculpture and painting programs but didn’t mention the architecture department.

The administrators thought no woman would want to choose architecture or compete to enter that part of the school. They were wrong. Wearing them down took so long that by the time the school of architecture finally admitted women, Kellogg had completed her studies. Her friend Julia Morgan became the first female student in the architecture program, gaining entrance in 1898 and graduating in 1902.

Credit due.

Upon her return to the States in 1900, Kellogg joined the firm of John R. Thomas in New York City. He is credited for being the most prolific architect of his day in the design of public and semi-public buildings. Her first important project was preparing plans for Thomas’ Hall of Records/Surrogate’s Court building near City Hall. She is credited with the design of the double staircase in the atrium of the building, an eye-catching masterpiece of Beaux-Arts design, the finest feature in this very ornate marble interior.

She spent six months working on the design, drawing hundreds of full-size details, showing every turn and ornamental detail of the staircase. She also made sketches, some full-sized, of every detail of the building, from the base moldings to the crown of the roof. She also made color sketches for the interior, so the contractors knew the combination of colors she wanted. She made similar color sketches of the floor, showing the design and each color of marble she specified.

Kellogg made the suggestion to Thomas that statues of Peter Stuyvesant and three other early Dutch governors should be placed in niches on the building. Figurative statuary was a prominent feature of grand Beaux-Arts design. Thomas thought it an excellent idea, and planned to include them, but died suddenly in 1901 before the ground was broken. The job should have been passed to her, but there were politics involved that denied her the opportunity.

Tammany Hall and its corrupt leadership were firmly in charge of the City and its mayor, Augustus Van Wyck. The Hall of Records was a very important building, so Van Wyck awarded the project to two totally inexperienced architects, Arthur J. Horgan and Vincent Slattery. At the time, they only had a few brownstones on their resumes, but were given one of the most important buildings of the day, thanks to Slattery’s longtime Tammany connections.

They totally ignored Kellogg’s statuary designs and went with their own. They used her sketches and notes, even while declaring them “incomplete.” Even though everything else in the design remained the same, Horgan & Slattery share credit on the cornerstone of the building with Thomas, and in subsequent writeups and accolades. Kellogg was not mentioned. Today, both the interior and the atrium of the building are New York City landmarks and are part of the State and National Register of Historic Places.

Founding her own firm.

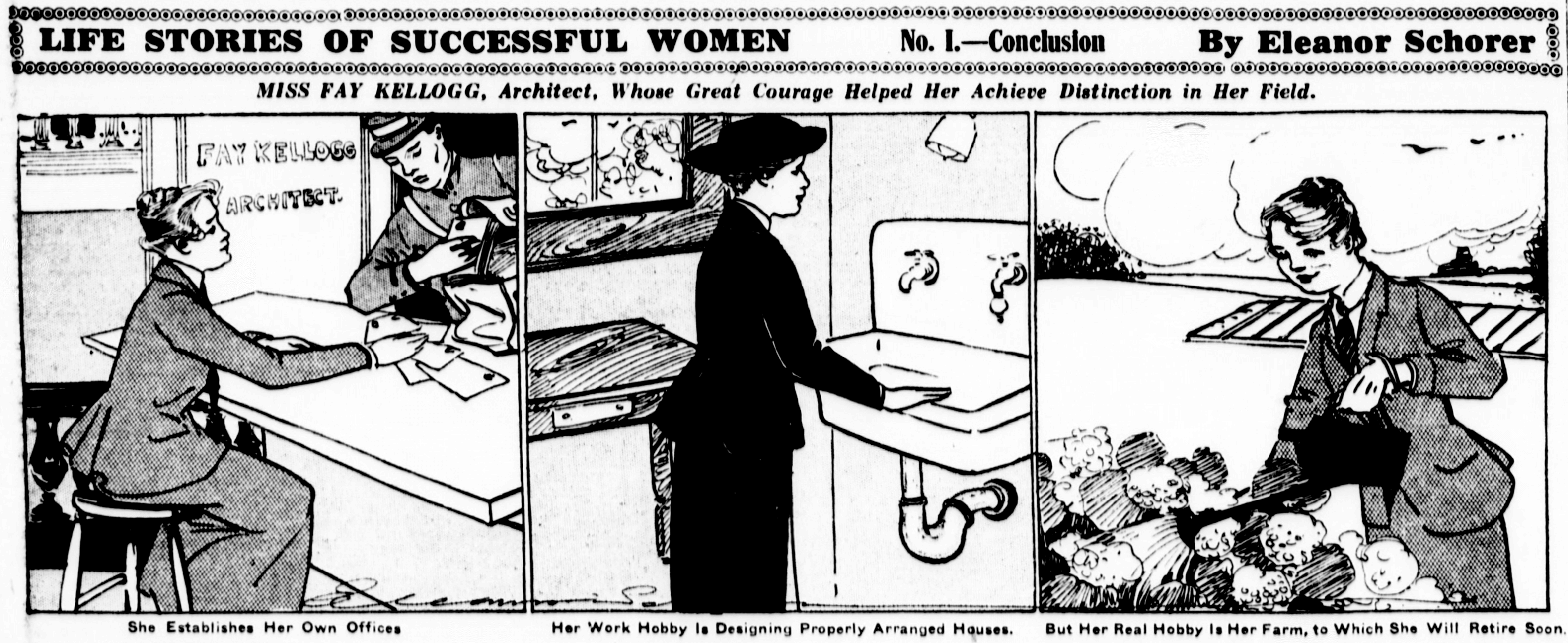

No longer willing to be subject to the whims of male architects who were not nearly as talented and experienced as she was, she decided to open her own architectural firm in 1903. Her office was the first female firm in the nation. The American News Company headquarters in New York City was her first large solo commission. American News published periodicals, postcards, comic books, and newspapers. They had more than 150 branches large and small across the country in buildings that were warehouses and distribution centers as well as news offices. After working on some small projects for them, Kellogg was put in charge of them all. Her New York City project was their main headquarters, located only blocks from the Hall of Records on Park Place. The project involved the demolition of several older buildings, the construction of a large new building on the site and the full renovation of six other adjoining buildings.

As she became more immersed in her commissions and projects, word got around that this petite female architect was at the vanguard of a group of career women who were changing the norms of early 20th century society. She was soon dubbed “the most prominent woman architect in the United States.” Reporters began following her on the worksite or sitting her down for interviews. Kellogg didn’t disappoint, she was quite forthright in her opinions.

A reporter wanted to interview her for a story in 1911, so she invited her to her worksite. There she followed her as she easily walked up unfinished stairs to confer with her workmen. She climbed ladders to walk along steel girders to inspect aspects of the roof, and easily maneuvered her way on scaffolding. She conducted her interview sitting on a girder out in the open, 10 stories above the ground, scaring the reporter half to death.

She told her, “I don’t think a woman architect ought to be satisfied with small pieces, but launch out into business buildings. That is where money and name are made. I don’t approve of a well-equipped woman creeping along; let her leap ahead as men do. All she needs is courage.”

Kellogg expressed more opinions and thoughts on women in architecture in other interviews. “Why shouldn’t a woman do as well at this profession as a man? In my opinion, the very nature of the field invites her services. In fact, it needs her. There can be no more anomalous condition than that which makes men the sole builders of our homes, while women, their chief occupants and governing spirits, are excluded from all participation in their preparation.”

When asked about the kinds of buildings she wanted to design, she said, “I don’t care so much for small pieces of architectural work. I only do big things.” She was excited about the opportunities offered in the relatively new form of steel construction and was eager to explore the new world of taller buildings, and modern construction. Although she designed many smaller structures during her career, she lived for the big projects, not afraid to go where no woman was allowed to go before. She got her chance, designing a 16-story skyscraper for American News in San Francisco.

Part of building is dealing with contractors and workmen. Kellogg was a familiar figure on site, dressed in sensible boots and skirt, and her round felt hat, always with her blueprints and drawings with her. Some men may have balked at working with a small, smartly dressed woman, but most of her workers loved her. “She isn’t afraid of anything,” her head of construction on the News Corp building said. “She is the most thorough man I ever met in architectural work.”

Her structural iron contractor was more familiar with working with women architects in Europe. He said, “She is more attentive to business than any man I know.” He went on to say, “It’s my first job with her, but I hope it won’t be my last. All the workmen like her. She is so considerate, but she can be, well, emphatic.” “When men have wanted to make concessions for me, I have said, ‘None of that,’ Kellogg told a reporter from Human Life magazine. “I want to be treated neither as a superior or as an inferior, but as an equal.” She also said, “If the men wanted to swear, I always let them. If it became necessary, I even swore myself.”

By 1911, Kellogg had her offices at 32 Union Square, with staff and enough projects to last for years. She designed railway stations and homes in the growing waterfront community of Howard Beach and in suburban Hollis, Queens. In Brooklyn she designed Women’s Memorial Hospital, which unfortunately is no longer standing, plus many, many more buildings in locations around the country.

Her busy schedule necessitated a place to rest and relax. In 1907 she purchased 15 acres of scrub land in Greenlawn, Long Island, part of Huntington Township. The acreage hadn’t seen any attention in 75 years. With her usual enthusiasm to get things done, she cleared the land of brambles and scrub, sometimes leading her team of horses, cutting down poison ivy and other invasive species with a scythe. She planted orchards, grew clovers and alfalfa and raised chickens for eggs she sold year round.

She also designed and built her house on the property. The house was often shared by her parents and siblings. Kellogg stayed there for half the year, dedicating as much work to maintaining the farm and its crops as she did to her other work. She was known to always wear khaki riding breeches, surveyors’ shoes, a khaki middy and a big hat while riding her tractors on weekends. She was once heard to say how much she loved wearing comfortable trousers, something she didn’t dare wear in Manhattan. She loved Greenlawn so much she designed a post office building with an apartment above for the post mistress in 1911.

Kellogg was also active in the suffragette movement, working to get women the vote. Of all the professional women sitting on the stage when famous English suffragette Mrs. Pankhurst spoke at Carnegie Hall in 1909, Kellogg was the only architect. ”I believe in my rights, and I think that women should vote for good roads, improvements of schools, and transportation,” she said.

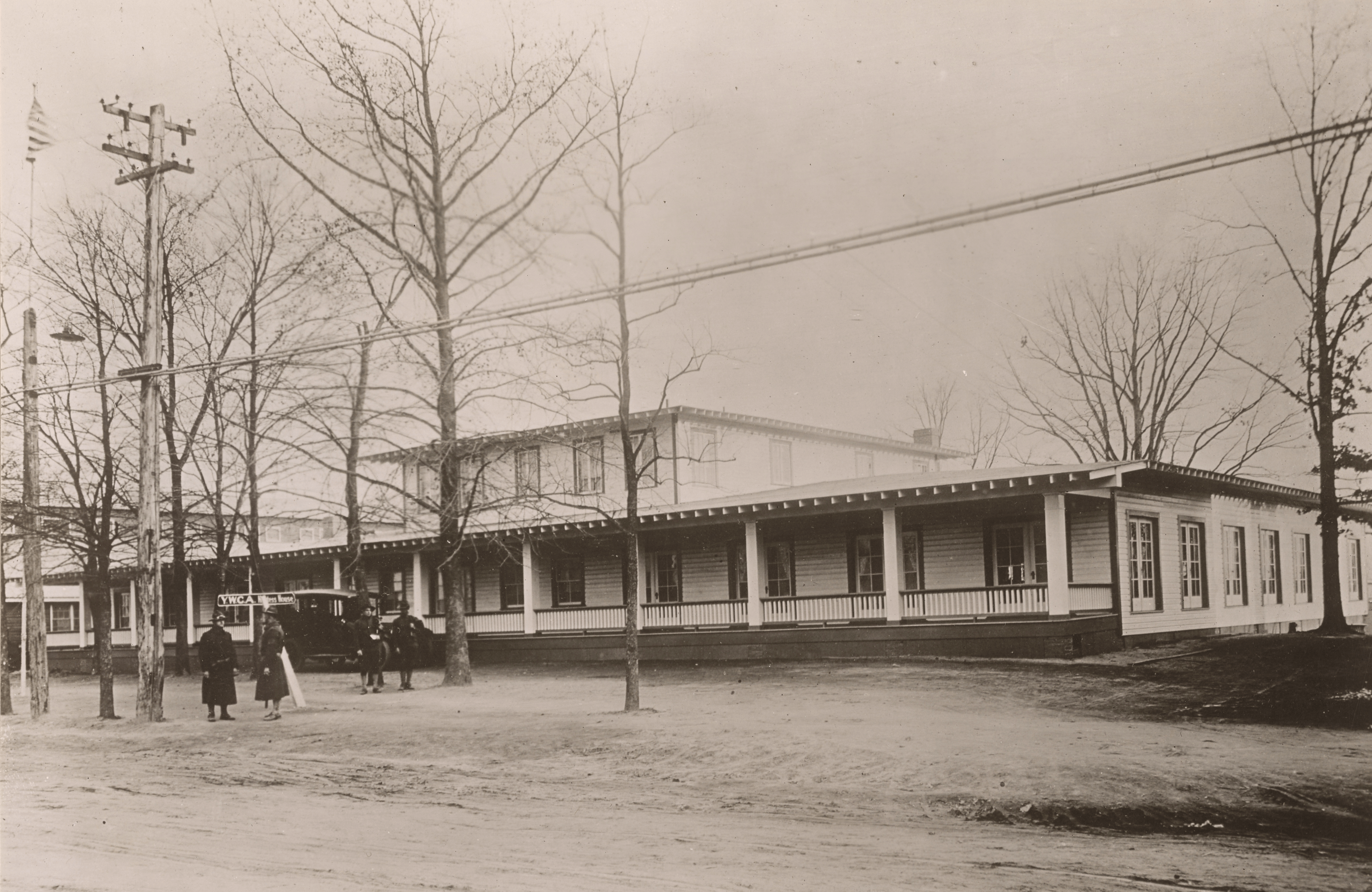

When the world plunged into war during 1917, Kellogg and her old friends Julia Morgan and Katherine Budd, who were also enjoying fine careers and media attention, were chosen by the YWCA to design “Hostess Houses” on several Southern army bases. The houses were designed as places where wives of soldiers could visit their husbands on base. She was working on a house in Camp Gordon in Atlanta when she fell ill. She tried to shake it off, in her usual manner, and refused to leave the project.

Her mother had to come down to Georgia and take her home. She died of a complication of diseases in her parent’s Stuyvesant Heights home on July 11th, 1918. She was 47 years old. Some reports of her death suggested the “war work” killed her, but modern scholars have determined that she was most likely one of the early victims of the Spanish flu pandemic that would spread to kill millions the next year. An army base would be a perfect petri dish for disease. Her funeral was held at her parents’ house, and she is buried in Brooklyn’s Evergreen Cemetery.

Her death was noted across the country, especially in New York. She was hailed as the foremost woman architect in America in her day. She wasn’t the first female architect but is credited as being the first to establish her own business. Several other women, especially Julia Morgan, would go on to do great things, all blazing the trail for female architects. Even today, women make up only 17 percent of licensed architects in America.

When asked about what she thought was her finest accomplishment, Kellogg said that it was being instrumental in opening the École des Beaux-Arts to women. When a female reporter asked her if she had problems with men taking orders from her, she said, “I’d like to see a man refuse an order I gave him.” The reporter wrote, “For a moment the woman architect’s sweet face had set in a look of contemptuous mastery. I saw the soul of steel that had overcome laws and the prejudices that are stronger than laws.” That was Fay Kellogg.

Related Stories

- Rene Chambellan, Art Deco Architecture’s Master Sculptor, in Brooklyn and Beyond

- Civic Pride: From Romanesque Revival to Neo-Brutalist, Brooklyn’s Firehouses Impress

- Architect Cass Gilbert Designed Innovative and Inspiring Public and Commercial Buildings

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment