Preservationists Hope New Landmarks Rules Will Better Protect Historic Buildings, Prevent Demos

A new plan announced by the Mayor’s Office to fortify protections for vulnerable historic buildings has been met with tentative optimism by preservation and community activists.

People gathered outside 441 Willoughby Avenue to try to stop demolition of the historic mansion last year. Photo by Anna Bradley-Smith

A new plan announced by the Mayor’s Office to fortify protections for vulnerable historic buildings has been met with tentative optimism by preservation and community activists, but they wait with bated breath for implementation.

The Vulnerable Historic Buildings Action Plan, released Friday, includes new guidelines designed to strengthen coordination between NYC’s Landmarks Preservation Commission and the Department of Buildings, and increase public transparency around violations on landmarked structures.

The new measures include:

- Increased interagency data sharing on the conditions of landmarked buildings.

- Increased review of landmarked buildings’ structural conditions prior to permits being issued.

- Joint LPC and DOB property inspections.

- Violation information on landmarked buildings being uploaded to LPC maps for public review.

To identify the primary risks to landmarked buildings, LPC held an “expert engineering” roundtable and engaged with stakeholders, including preservation and community groups, and preservation professionals from across the country, according to a press release.

That process identified three main issues: pre-existing unknown structural conditions, demolition by neglect, and illegal work by contractors/contractor error. As such, the new rules are designed to target those risks and allow the city and local communities to proactively protect historic buildings.

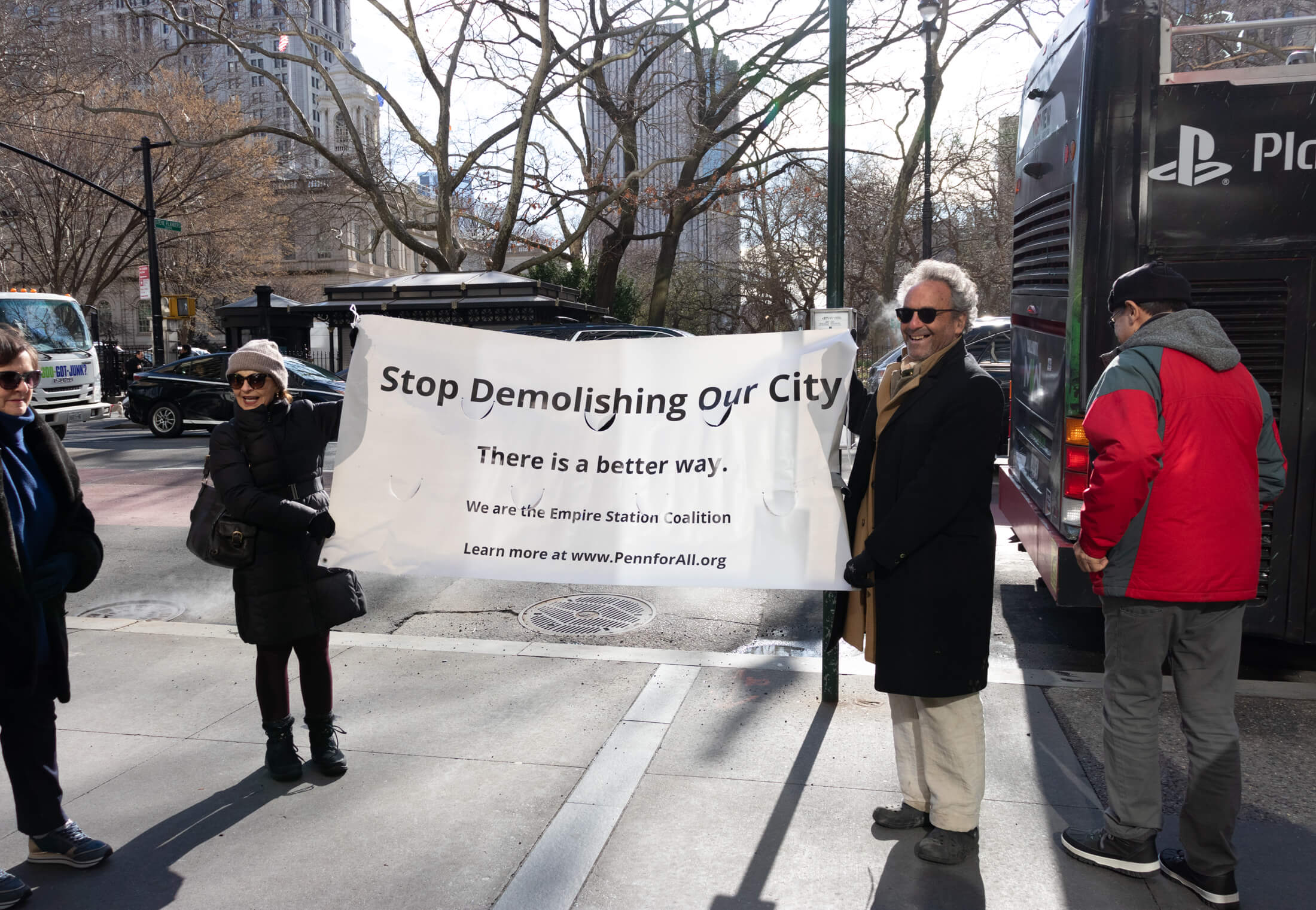

Advocates have been loudly calling for change to LPC processes following what many say is a disturbing trend of demolition of landmarked structures across the city. At a recent rally around 100 people accused the agency of being “captured” by the real estate industry and said it is in need of deep reform.

The Historic Districts Council, which attended the protest, has been in contact with LPC about the issues, executive director Frampton Tolbert said. In February, the group sent the agency policy recommendations detailing ways LPC and DOB could work together to prevent demolition of landmarked structures going forward.

“We are pleased that several of the actions LPC is proposing come directly from our recommendations and communication with LPC,” Tolbert said. “Now comes the hard part of implementation to make sure this alarming trend stops. I think transparency and regular communication is key.”

In addition to the recommendations, HDC also sent LPC a list of 29 landmarked buildings that are currently at risk, nine of which are in Brooklyn. HDC hopes the list will be the foundation of a citywide database of landmarked buildings at risk.

In a press release, Mayor Eric Adams, along with LPC Chair Sarah Carroll and DOB Acting Commissioner Kazimir Vilenchik, said the new plan focuses on early detection of risks to designated buildings, more robust engineering oversight, increased coordination and communication between LPC and DOB, and enhanced community tools.

“New York City is home to some of our nation’s richest history, and protecting our most fragile landmark buildings is a crucial way to ensure those stories continue to be told,” Adams said in the press release. “I am proud of our administration’s ability to drill down, locate the gaps in the preservation process, and create a plan to fix it. This action plan will undoubtedly help save the incredible historic buildings that decorate our city.”

The plan also refers to demolition permits being issued for historic buildings that are under consideration for landmarking, recalling the 2022 demolition of Jacob Dangler mansion at 441 Willoughby Avenue in Bed Stuy. It was being considered for designation by the LPC as it was torn down by developer Tomer Erlich.

Following the demolition, LPC Chair Carroll said due to DOB’s lagging permit system, neither she nor her staff were made aware the developer’s application for the demolition permit had been completed a day after the mansion was calendared for designation by LPC.

To address that, the plan requires all new full demolition jobs to be filed in DOB’s new DOB NOW: Build system instead of the previously used Buildings Information System. The new system will create more transparency and accountability, according to the press release. “DOB will also require certain jobs filed in BIS prior to DOB NOW’s launch to be refiled in DOB NOW.”

Molly Salas, a spokesperson for Justice for 441 Willoughby (a group formed to advocate for the now-empty lot the Jacob Dangler mansion sat on), said if the demise of the mansion was due to the demolition permits being filed under the BIS system instead of DOB NOW, “that’s no ‘technological error’ as LPC has indicated.” “That’s a century of history demolished for developer greed because of an outdated spreadsheet. The agencies should be embarrassed, and these reforms are necessary,” she said.

Salas added the new plan is a step toward accountability for LPC and DOB and saids the group is eager to see how LPC engages with vulnerable communities moving forward. “While we have an open mind and hope these meaningful changes are actually implemented, it is clear that these reforms were born out of energy, attention, and calls for accountability from communities like ours throughout the city experiencing the same kinds of unnecessary demolition.”

Salas said Justice for 441 Willoughby also wants to see DOB bar certain developers who “have demolished landmarks or soon-to-be designated landmarks through intentional negligence” from obtaining demolition permits in the city. “We are encouraged to see accountability from the city agencies tasked with oversight, but accountability of bad actors should be at the forefront as well.”

Lauren Cawdrey, vice president of the Willoughby Nostrand Marcy Block Association — which has also been active in advocating for changes to the preservation process following the demolition of the Dangler mansion — said she is hopeful more oversight and accountability will be applied in the future, and that the new plan isn’t just for appearances.

“This announcement is the beginning of an attempt at fixing a flawed system and we hope both agencies will work with the community to repair the harm caused by the demolition and help plan for the future of the site.”

While the announcement is seen as a step in the right direction by the preservation community, concerns still remain about other aspects of how LPC is run. Lynn Ellsworth, who founded Human-scale NYC – a citywide coalition of community groups focused on planning, development, public space, and preservation issues – said while the initiative is welcome, it “reads like a weak attempt to fiddle with the regulatory process via DOB to avoid the demolition mistakes we’ve seen recently. But DOB is not exactly the most trustworthy of agencies, as we all know by reading the press.”

Human-scale NYC organized the recent rally where 21 community groups and elected leaders accused the LPC of giving one-sided access to the development community, which they said it does not give to the general public. They also alleged the commission has failed to protect current landmarks as well as designate worthy new ones. A white paper released by Human-scale NYC to coincide with the rally called for 11 structural reforms to protect the “visual character and history of our city.”

Some of the most concerning trends alleged in the white paper are that the LPC chair has accrued “despotic regulatory power,” that the agency is working with developers behind closed doors to their benefit, and that the LPC is unwilling to designate landmarks or historic districts if there is any “buildable space in play.”

Ellsworth said that while fiddling with regulatory processes is needed from time to time, “the problems of capture of the LPC by the real estate industry that we have been calling attention [to] are totally ignored: Mayoral and administration interference with LPC, conflicts of interest, and the undemocratic consolidation of power within the LPC into the hands of an unaccountable chair — to the detriment of the other appointed commissioners,” she said. “The LPC needs substantial reform to fix these problems.”

An LPC spokesperson previously told Brownstoner the agency “is wholeheartedly committed to preserving the city’s historically, culturally, and architecturally significant buildings and neighborhoods,” and that it categorically rejects any assertions of conflicts of interest.

“The commission and staff make thoughtful determinations based on best preservation practices, careful analysis, and thoughtful review. We appreciate feedback from communities and elected officials and are happy to work together with them to make sure we are doing the best we can to protect and preserve the city’s historic built environment.”

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- Preservationists Charge Landmarks Commission Does Real Estate Lobby’s Bidding, Violating Law

- Shaken by Recent Decisions, Preservationists Say Landmarks Commission Is Not Doing Its Job

- After Hasty Demo of Bed Stuy’s Dangler Mansion Short Circuits Landmark Process, LPC Speaks Out

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment