Civic Pride: From Romanesque Revival to Neo-Brutalist, Brooklyn's Firehouses Impress

Any municipality may have beautiful homes, but what really makes a city great in terms of outward appearance is the quality of its civic buildings.

The firehouse for Engine 252 at 617 Central Avenue in Bushwick, considered by many to be Brooklyn’s most beautiful, was designed by the Parfitt Brothers and opened in 1897. Photo by Susan De Vries

Any municipality may have beautiful homes and impressive cultural, religious, and commercial structures, but what really makes a city great in terms of outward appearance is the quality and quantity of its civic buildings. The architecture and appearance of schools, courthouses, police stations, firehouses, and infrastructure buildings were important in the late 19th century. They were something everyone could point to and be proud of, an outward representation of the responsibility city government had to take care of its citizens.

Brooklyn began as a wooden village, which soon grew into a town. One of the greatest dangers to any town has always been fire. We have all seen period movies where a building catches fire and the townspeople rush out and form a bucket brigade from the nearest body of water to the burning building. Such efforts were heroic, but relatively unorganized and inefficient. Towns realized that they needed something better, and volunteer fire brigades were organized.

Brooklyn’s first volunteer fire department was established in Brooklyn Heights in 1785. The company had five firefighters and one engineer, the man who drove the wagon. They all were signed up for a one-year term. The town firehouse, a barn for equipment and horses, was near today’s Cadman Plaza.

By the mid-19th century, Brooklyn’s neighborhoods had many fire brigades, with almost 3,000 men between them. But they were totally independent of each other. Each company raised its own money, had its own uniforms, equipment, and regulations. Most of the units were up and down the East River, as the industry, businesses, and homes there were the most valuable pieces of real estate.

But despite their numbers, this was still the age of gas and kerosene lighting, wood and coal fireplace heating, and unregulated industries storing or manufacturing volatile products next to flammable materials. Fires were frequent, as was the loss of life and property. The city’s citizens, businesses, and fire insurance companies demanded a professional firefighting department with paid firefighters.

A bill to establish a city fire department was introduced in the Brooklyn City Council in 1858 but didn’t pass. It took another 10 years, and several hundred fires, for the governor to sign legislation establishing the Brooklyn Fire Department, or BFD. The new agency began with 13 engine companies and six ladder companies. Most of these were once-volunteer organizations, and many of the men hired were experienced volunteers.

The earliest firehouses still standing in Brooklyn date from the late 1870s. They are brick buildings and were designed to hold the engine or ladder wagons and the horses that drew them. Consequently, these stations, located mid block on residential streets, look like the stables and carriage houses around them. Some of them may have been stables before. They all are two-story buildings with a wide central entrance. The latest equipment of the day was a four-wheeled wagon with a powerful steam engine, drawn by four horses.

The second story held the command office, company room, and dormitory. There were no cooking facilities; firemen generally lived close enough to walk home for meals. They were allowed an hour each for lunch and dinner and given only a 12-hour leave in a 10-day workweek, 24 hours a day. For this service, they received about $900 a year, with single men preferred for the job. It was a lucky married man whose wife brought him meals.

In 1894, a new era began for the Brooklyn Fire Department. Frederick W. Wurster became the new fire commissioner. That year also saw the city of Brooklyn annex the once-independent towns of Flatbush, New Utrecht, Flatlands, and Gravesend. The new commissioner and his staff began an ambitious program to hire more men, update equipment, and build firehouses in the annexed neighborhoods. In 1895 alone, four new companies were organized and 18 new firehouses were either under construction or in the planning stages.

Like its neighbor across the river, Brooklyn was determined to build impressive new civic buildings that were worthy of first-class modern cities. Manhattan hired Napoleon LeBrun to design their new houses. He created gorgeous Beaux-Arts firehouses, many of which are landmarks today. Here in Brooklyn, the city commissioned several architects for their projects, all of whom stepped up to the plate and designed unique, beautiful, and highly functional stations. All were architects already creating the upscale neighborhoods of Brooklyn.

A master touch

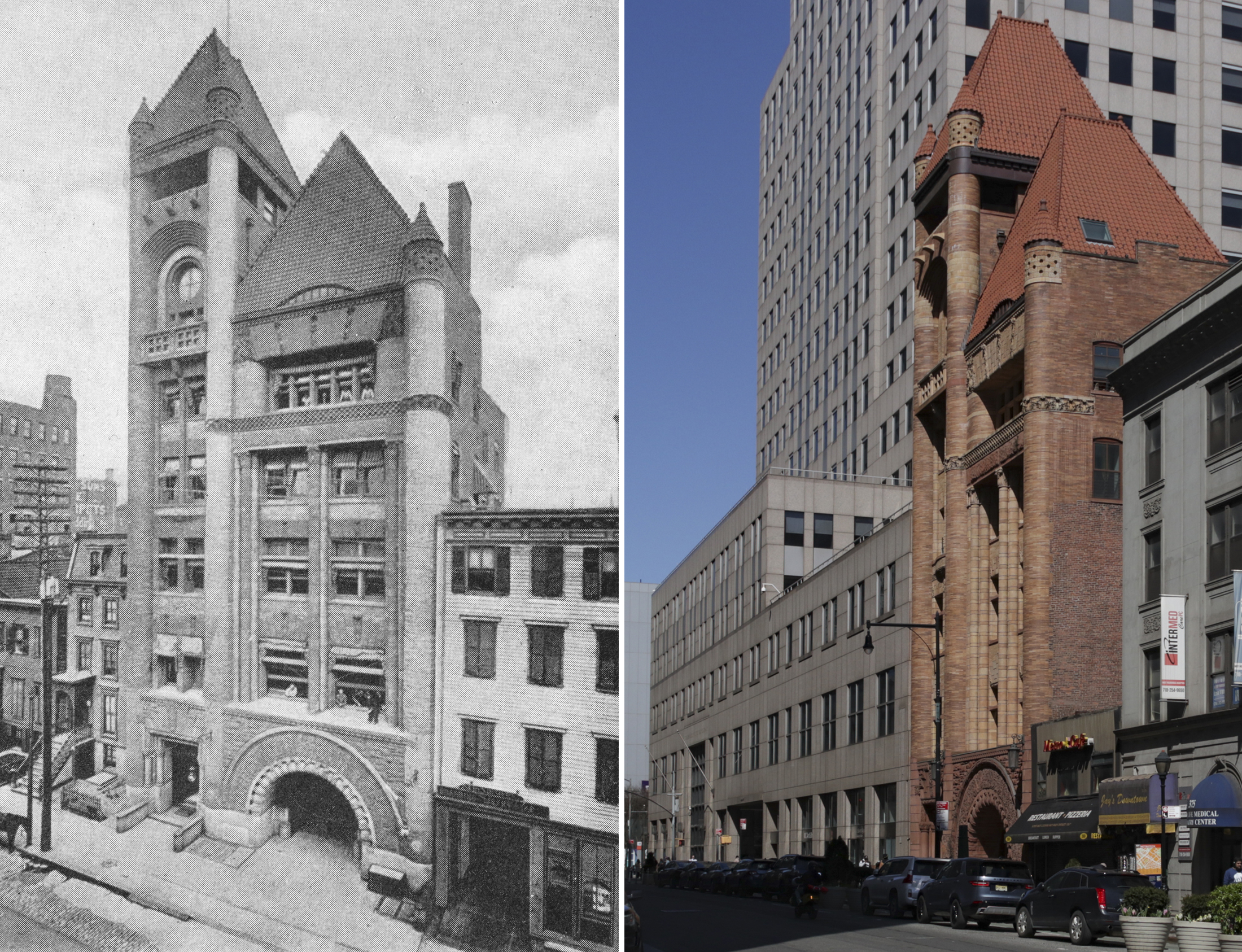

The first thing the expanded Brooklyn Fire Department needed was a new headquarters in Downtown Brooklyn. This building would house a fire company, as well as the division and central office space the department would require. It was important that this building be both functional and impressive.

The city chose Brooklyn’s Frank Freeman as architect. The Romanesque Revival style of architecture, a powerful, masculine, and impressive style, was regarded as the proper mode for large civic structures. Freeman was a master of the Romanesque style and had already designed the Herman Behr mansion in the Heights and downtown’s massive Germania and Jefferson clubs, and would soon go on to create the Eagle Warehouse near the Fulton Ferry.

Freeman designed a truly monumental six-story headquarters at 365 Jay Street, bristling with huge arched entrances and windows, towers, multiple rooflines, and lots of massive terra-cotta ornamentation, especially around the entrance. The building was completed in 1892 and is today a New York City landmark. The ladder and engine wagons and their teams of horses racing out of the building, the men scrambling to jump on, was a thrilling sight for many years.

Parfitt Brothers, one of the top architectural firms in Brooklyn, was awarded a large contract to design fire stations, primarily in the newly annexed neighborhoods. Their two masterpieces were Engine 252 at 617 Central Avenue in Bushwick and Engine 253 at 2425 86th Street in Bensonhurst. Both were designed with elements that were a reminder of Brooklyn’s Dutch origins.

The firehouse for Engine 252 incorporates the necessary wide entrance for the wagons and equipment with a Flemish Revival facade featuring a scrolled front gable and stepped end gables. Two handsome banks of windows provide natural light. The offices and sleeping room for the officers, as well as a dorm room for the men, were on the second floor, with a day room on the third. The station opened in 1897 and is considered by many to be Brooklyn’s most beautiful firehouse.

Engine 253’s home in Bensonhurst is pure Dutch Revival, with that style’s characteristic stepped roofline. The Parfitts used this motif on every street-facing element of the building, including the tower, punctuated by windows. The multi-story tower was not only highly decorative, but also functional, a place to hang and dry the fire hoses. Many of the best fire stations of this period incorporated a tower into their design. This firehouse opened for service in 1895.

Bensonhurst-by-the-Sea and Borough Park, both once part of New Utrecht, were just starting to develop as suburban neighborhoods when the project started. Walter and Albert Parfitt were new residents in Bensonhurst and were designing many of the buildings there. The Parfitts designed two identical firehouses, Engine 243 in Bensonhurst and Engine 247 in Borough Park. Walter Parfitt, working solo, designed Engine 220 and Squad 1 in Park Slope and Engine 227 in Brownsville. All are fine buildings. Engine 252, 253, and 220 are New York City landmarks.

Another well-respected architect, one who worked only on upscale projects, was Danish architect Peter J. Lauritzen. His clubhouses, mansions, and majestic Offerman building in Downtown Brooklyn all reflect his love of Romanesque massing and mix of structural and ornamental materials. He carried these elements over into his civic designs, including eight firehouses for the BFD, and simplified them for the new Renaissance Revival style.

Fire stations for Engines 235 and 236, in Bedford Stuyvesant and East New York, respectively, are almost identical. They are both built in a golden brick, with a steep gable roofline extending higher than the third story of the building. Engine 235 features carved-stone Byzantine leaf ornamentation, a frequent design element of the day. The highlight is the twin profiles of a fireman at the base of the gable. Both buildings were completed in 1895.

His Engine 237 in Bushwick, 238 in Greenpoint, and 239 in Park Slope are of a similar design, varying primarily in materials. They were built between 1895 and 1898. His Ladder 114, a diminutive but elegant and ornamental Renaissance Revival gem, was built in 1897 and stands mid block on 5th Avenue in Sunset Park.

Only one of his firehouses is a city landmark today. Engine 240, in Windsor Terrace, built in 1895, harkens back to the Romanesque Revival but in limestone, with a prominent second-story arched window and a hose tower, once topped with a peaked turret. A similar design in red brick with limestone trim stands in Prospect Lefferts Gardens. Here, for Engine 249, Lauritzen combined Flemish and medieval elements in the design.

The 20th Century and Beyond

In 1898, the Brooklyn Fire Department merged with the Fire Department of New York, or FDNY, when Brooklyn became a part of greater New York City. The administration and regulations of FDNY now covered all five boroughs. The Downtown Brooklyn station was no longer needed as a headquarters but remained a working firehouse until the 1970s.

The building of new fire stations in Brooklyn continued. The designs were not as unique as those of Freeman, the Parfitts, and Lauritzen, but some especially fine examples were constructed. The most impressive was the Beaux-Arts beauty Engine 224 on Hicks Street in the Heights, built in 1904. Other stations around the borough, built between 1912 and 1932, were now designed for motor vehicles, not horse-drawn wagons. Some were better designed than others, but all were still adhering to the idea that a civic building had to have gravitas and good design.

The Great Depression, followed by World War II and the Korean War, saw all municipal building projects put on the back burner. Starting in the late 1950s, construction started up again, with the city replacing many of the oldest fire stations with new buildings. Unfortunately, in this age of Brutalist and Postmodern architecture, the idea that firehouses and police stations should be monumental and memorable was lost. The new buildings were functional, with needed upgrades for equipment and staffing, but no one would ever call them beautiful. “Build as cheaply as possible and forget aesthetics” seemed to be the mandate from the budget office.

Many of these new buildings were erected in neighborhoods that were undergoing extreme economic duress. In many cases, the architecture is more suited for a fortress, designed to protect the firefighters inside from the people they serve. Design wise, they remain banal boxes, their windows small and high; their bay doors, when open, the only real source of natural light. Engine 207 and Ladder 110 on Tillary Street near the Manhattan Bridge and Flatbush Extension, built in 1971, is an example of the style of the period. The city fathers of the 1890s would have been appalled.

Today, in the 21st century, architects are rethinking the firehouse and other civic architecture. While budget is always a concern, that doesn’t mean buildings must be unattractive. Brooklyn’s resurgence in importance as a place to live and work necessitates modern fire stations and firefighting methods. 9/11 cemented that importance, with so many first responder lives ended.

Rescue 2, Brooklyn’s elite unit, needed a new firehouse. They are deployed to rescue the rescuers and respond to various emergency situations. Their old station, one of the old two-story stable buildings, was no longer adequate, especially after the World Trade Center attack. In 2019, the city unveiled its new, modern facility, located in Ocean Hill.

The building was designed by Studio Gang, a Chicago firm with an office in New York. It functions not only as a spacious home base for the unit but is also a training center. The firehouse has enough room to store all the equipment needed for any kind of rescue, including scuba gear. The open spaces and levels can be staged to simulate various New York building scenarios for safe training sessions, not only for Rescue 2’s team but for firefighters across the city.

In addition, the building is equipped with 21st century energy-saving technology, including a green roof, geothermal HVAC, and solar water-heating systems.

The design stands out. Unlike its earlier Brutalist cousins, this building, with its bright red and concrete facade, is not an off-putting fortress. The huge horizontal and vertical voids allow light and natural ventilation into the building. The playful arrangement of shapes, voids, materials, and finishes invites further investigation to see how it all works.

There are several other new firehouses in Brooklyn, all with innovative and interesting designs. Civic design, like all architecture, changes with the times. We can only hope that Brooklyn keeps the best of the old and proceeds with the best of the new, as well.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- Journey by Faith: The Story of Brooklyn’s Black Churches

- Major Talent: Parfitt Brothers Make Their Mark on Brooklyn

- Living the Good Life on Eastern Parkway

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment