The Lore of 13 Pineapple Street, One of Brooklyn Heights' Historic Wood Frame Houses

Even in a neighborhood filled with architectural delights, the generously wide, gray-shingled facade seems to hint at an interesting past.

It’s a house that invites a second look from the passerby. Even in a neighborhood filled with architectural delights, the generously wide, gray-shingled facade seems to hint at an interesting past. Located on one of the charming fruit streets of northern Brooklyn Heights, 13 Pineapple stands apart from its brick and brownstone neighbors, a wood-frame, Federal-style reminder of an earlier time in the neighborhood.

With a neighborhood that has been documented over the centuries by writers, artists and historians, and was even the first historic district designated in New York City, it might be safe to assume that each Brooklyn Heights house has a well-traced story charting its architectural and social history. That would be wrong. Each dive into a Brooklyn Heights building involves complicated research and sorting through endlessly entertaining folklore. In the case of 13 Pineapple Street, some of that folklore was enshrined into the collective consciousness by none other than Truman Capote.

The Folklore

A house with some colorful tales attached to it is not unusual; in fact, it’s expected in a building that has almost 200 years of history behind it. What is intriguing about 13 Pineapple Street is that much of the folklore surrounding the house dates from the 1930s to the 1960s. Few contemporary accounts from the 19th century have emerged, nor even many stories from the early 20th century, when so much history was being delightfully embroidered.

The stories that do emerge — a connection to a ship captain, a ghostly presence, a 1790 construction date, a wife insisting on the size of the house being doubled, and a tale of it being moved from another location — all seem to have begun, or at least begun to appear consistently in print, after 1930. Most are stories repeated by area residents who either lived near or in 13 Pineapple Street. The most notable of those is the Capote nod in his essay “Brooklyn Heights: A Personal Memoir,” published in February of 1959 in Holiday magazine. “A silvery gray, shingle-wood Colonial shaded by trees robustly leafed, it was built in 1790, the home of a sea captain,” he wrote of the house, perhaps inspired by the glimpse of it obtained from his back porch at 70 Willow Street.

The fun of old house folklore is figuring out where and how such stories emerged. There’s often a kernel of truth to at least some of the tales, and such is the case with 13 Pineapple Street.

The Early Years

The construction year of 1790 is not an uncommon claim in Brooklyn Heights. Many sources often assert another of the grand early houses of the neighborhood, 24 Middagh Street, also dates to that year. However, much like 24 Middagh Street, the house on Pineapple more likely has its origins in the 1820s than the 1790s.

Local historian Jeremy Lechtzin has done a deep dive into the history of a large swath of buildings in the neighborhood and his extensive research on 13 Pineapple Street seems to confirm a circa 1822 date of construction. He found that Ezra Woodhull purchased much of the land on the north side of Pineapple Street in 1820 and census, deeds and other records he consulted seem to indicate a house located at 13 Pineapple Street soon after.

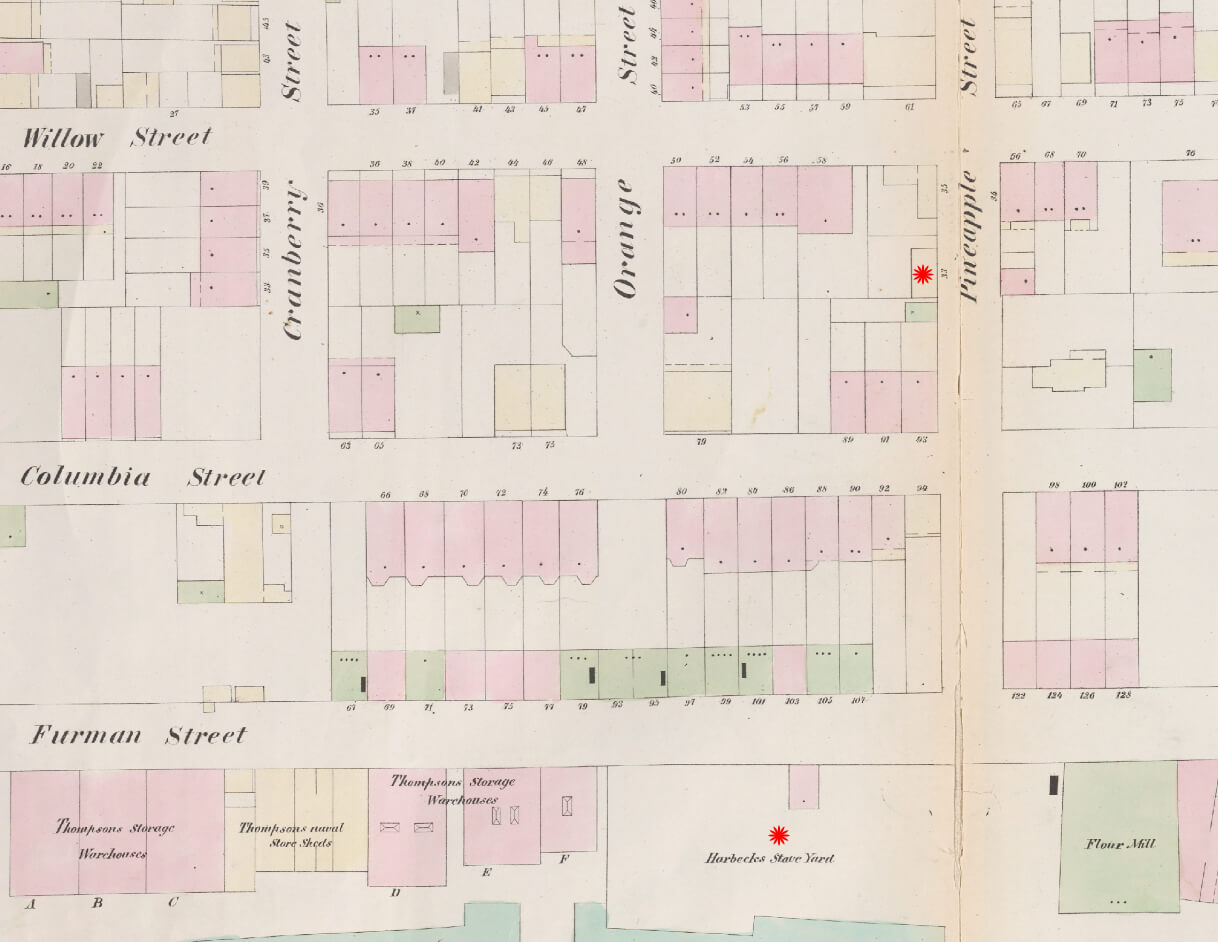

City directories can sometimes offer clues to residential patterns, and Brooklynites are listed living in houses located on Pineapple Street from the earliest directory of 1822. Alas, those early listings don’t include an address, merely signifying a resident as being on or near the street. It isn’t until the 1830s that 13 Pineapple begins appearing by address and then it was known as No. 33, an address it would retain until a street renumbering in the 1870s.

As to whether the house was moved from another location, while the claim is not as unusual as it might sound, little concrete evidence has been found to support it. House moving was not unheard of in the 19th century. Whether saving a house from the construction of a new road or moving it to a more desirable spot, the skilled labor to move a frame house would have been available. An 1832 article in the New York Evening Post described frame houses “moved on rollers from one street to another” as being a common occurrence. While 19th century historian Henry Stiles makes a reference to a house being moved from Middagh Street to Pineapple Street in his book A History of The City of Brooklyn, no further details are provided so it is difficult to prove this references 13 Pineapple Street.

Regardless, the house was in place on Pineapple Street by the early 1820s. What exact shape it took when it was first constructed is up for debate. Today, a look at the house shows a Federal-style wood-frame house five bays wide with a center entrance and three floors set above a garden level. For a house of the style and time, a peaked roof with dormers might be expected. But its bracketed cornice gives a hint of later 19th century alteration, and a discerning eye might suspect some 20th century Colonial Revival sprucing up.

Beginning in the 1950s, an owner of the house claimed in several newspaper accounts that the house had been enlarged from three bays to five in the 19th century. No conclusive evidence has been found to affirm this but examining the house itself does provide a few tantalizing hints. Interestingly, only one side of the house, the western side, has a cellar, perhaps putting into an addition what was lacking in the original construction. A critical view of the front facade shows that the spacing of the windows is different on either side of the central door. Looking at the shutters on the parlor floor windows makes this very clear — the spacing between the windows is much wider on the west side than it is on the east. In appearance the house may well have originally more closely resembled 24 Middagh Street — a three bay wood-frame house with a peaked roof and dormers.

If the house was altered or added to after its circa 1822 construction, those changes were in place by 1855, the year that 13 Pineapple appears on a map by William Perris. The house, labeled as No. 33, is drawn at its present width. By the time the Perris map was published, 13 Pineapple Street was home to the family that would live there for the next 85 years.

The Coleman Family Arrives

While the house was built circa 1822, most of the early residents appear to have been renters, appearing in one city directory and gone by the next year. It wasn’t until John and Mary Coleman moved into the house in 1852 that there is a family with any significant tenure.

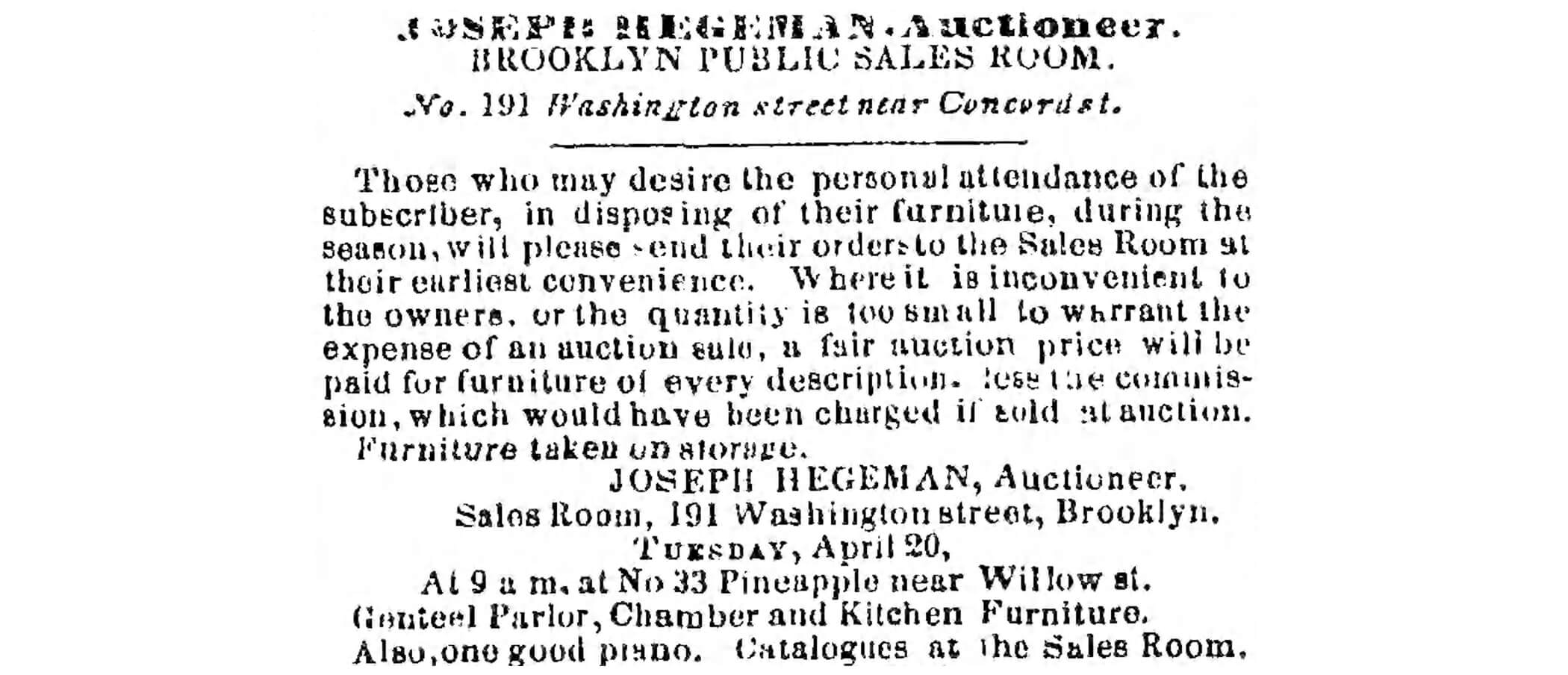

The house, which had passed through a few hands of ownership since the time of Ezra Woodhull, was put up for sale again in 1849, this time appearing in a sales notice by address. In the spring of 1852 an auction was held in the house for “genteel parlor, chamber and kitchen furniture” and it is believed that John and Mary Coleman moved in following the sale. A deed for the house, dug up by Jeremy Lechtzin, shows that the Coleman family, already residing there as tenants, purchased the house for $3,250 early in 1853.

The family wasn’t new to the borough. While John was born in New Jersey and Mary in Scotland, they had been living in Brooklyn since at least the 1840s. The 1850 census and the directory for that year places the family as living in Vinegar Hill before making the move to Brooklyn Heights.

Despite their long tenure at 13 Pineapple Street, it took a bit of digging to find out more about the family. For living in what is now considered a substantial house in the neighborhood, the Coleman family was not part of a wealthy social set. They were a working class family that seldom made an appearance in the local papers. John was a cooper, a worker skilled in using wooden staves (timber) to create barrels, buckets and other containers held together with metal.

John Coleman’s obituary in 1893 states that he had his own cooperage in the late 1840s but that he also was for some years “a state inspector of staves at Harbeck’s stores.” The house at 13 Pineapple Street certainly made for a fast commute. Just a jaunt of a few blocks would have brought Coleman to the bustling Brooklyn Heights waterfront and Harbeck’s stores. Warehouses, or stores, lined the waterfront, holding timber, coffee, spices and other goods coming and going through the busy port.

The Perris map of 1855 shows business wasn’t just confined to the waterfront. Mixed among the frame and brick dwellings of the neighborhood were buildings classified as “specially hazardous” by the map maker. The list included stables, boat builders, brewers and other manufacturers. One such business, located in what was classified as a first-class frame building, was right next to 13 Pineapple Street.

The hazards of mixing manufacturing and frame dwellings would not have been lost on John Coleman. According to his obituary he was also a “veteran fireman,” likely part of one of Brooklyn’s volunteer companies. Before a formal Brooklyn Fire Department was established in 1869, local companies were critical for responding to the fires that frequently sprung up, particularly in densely settled neighborhoods with frame buildings. John and Mary Coleman also would likely have seen the impact of a major fire firsthand. Just four years before they moved into 13 Pineapple Street, a massive blaze decimated multiple blocks of property near Brooklyn Heights.

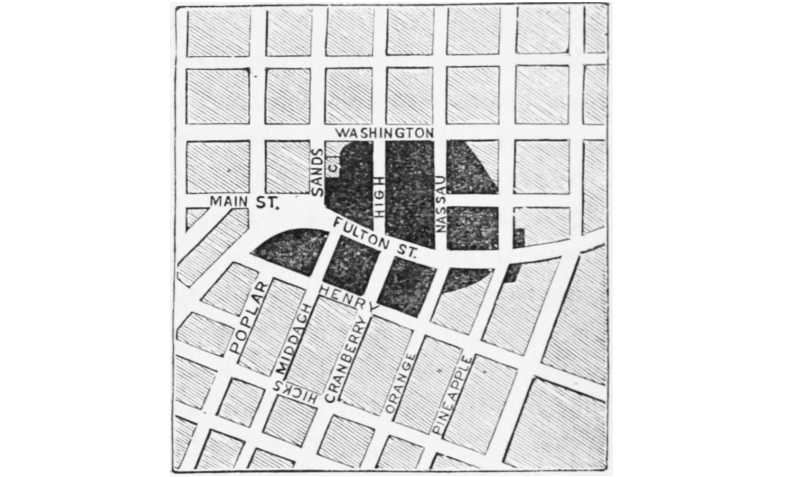

Late in the evening of September 9, 1848, flames broke out in an upholstery shop on Fulton Street. The fire quickly spread to a neighboring paint shop on Middagh Street, then spread to Pineapple Street and across Fulton to Washington Street. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle dubbed it an “awful conflagration” and estimated that as many as 250 buildings were lost. While the enormous fire of 1848 didn’t touch 13 Pineapple Street, it got within a few blocks of the house. Local papers mourned the loss of life and property but they also quickly reported on efforts to rebuild.

When the Coleman family moved from Vinegar Hill to Brooklyn Heights a few years after the fire, Fulton Street had already largely been rebuilt. A few years later, the Colemans renovated the exterior of 13 Pineapple Street. That change would involve the fire code.

In June of 1876, a report from the Brooklyn Common Council was printed in The Brooklyn Union, and it makes an interesting reference to the house. The newspaper reported that the Committee on Fire had voted to amend the provisions of a section of code in the city charter as it applied to 13 Pineapple. That code regulated the roofing of wooden buildings, in particular the substitution of a flat roof in place of a peaked one. According to the code, roofing materials were required to be fireproof and no building could be raised higher than 35 feet from the sidewalk. No record of the completion of roof work on the Coleman’s house was found, but the heavy, bracketed cornice certainly aligns with a late 1870s construction period.

The alteration to the house may have indicated a wish for a more modern appearance — as well as a family in good financial shape. Census records show that in the years before the renovation the Colemans were able to cut back on the number of boarders they hosted in their residence. The census record of 1855 shows nine family members and seven boarders, for a total of 16 people living in the frame dwelling. By the 1870 census there weren’t any boarders in the house, and it was occupied solely by the couple and their children.

Seven Coleman children have been tracked down so far, six daughters and one son, all born between the 1830s and 1850s. While three children would leave Pineapple Street, the rest spent most of their lives in the house.

Daughters Sarah, Mary and Agnes all married and moved out of the house. Sarah Coleman Hartman settled in what is now Dumbo with her silversmith husband while Agnes Coleman Mills moved to Hoboken and had two daughters. Mary Ann Coleman Roach provides a possible connection to the ship captain rumors surrounding the house. Her husband, Garrett Roach, was the son of great 19th century shipbuilder John Roach and worked in the family business. Mary and Garrett settled in Manhattan and had two sons.

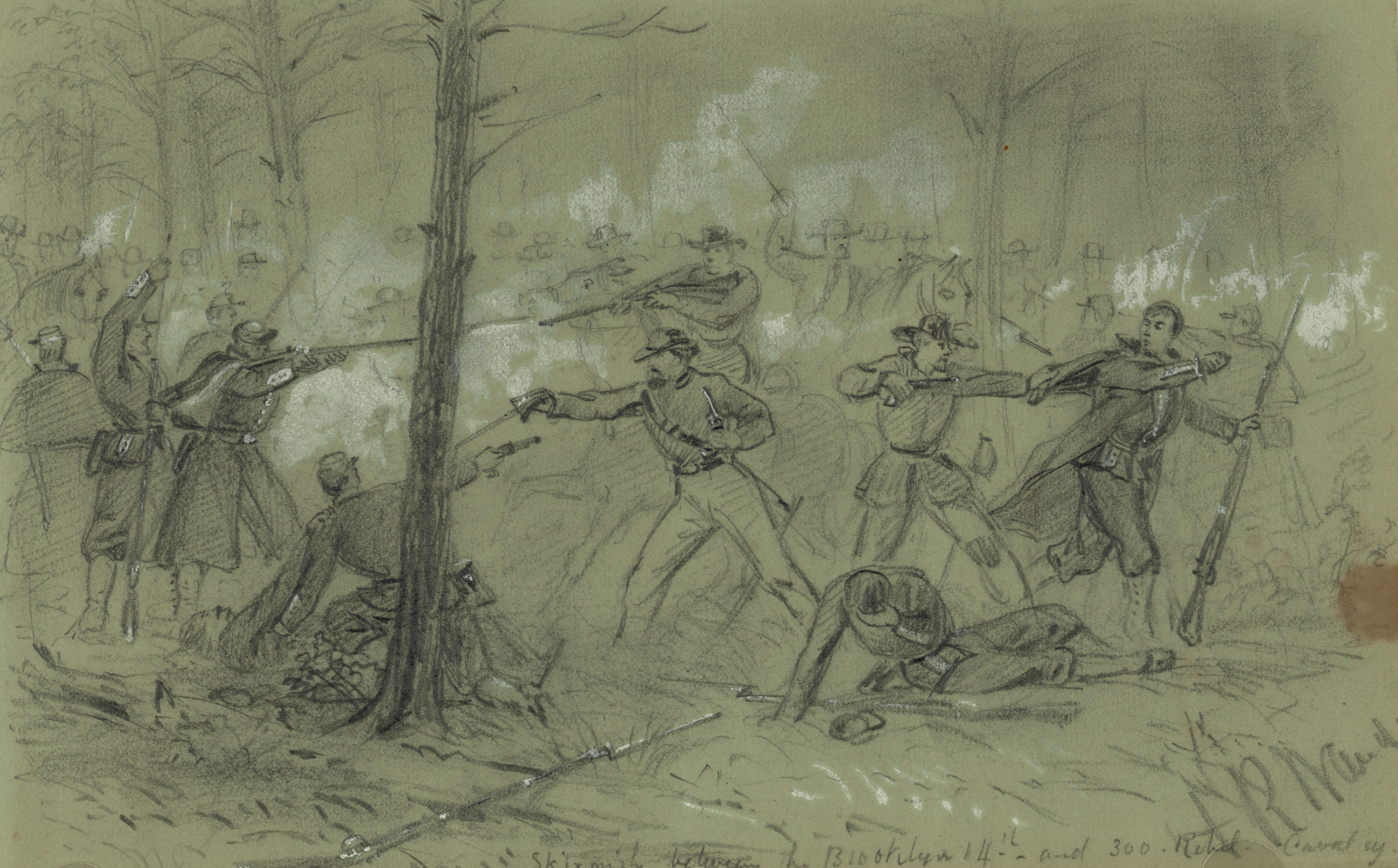

Children John Jr., Julia, Caroline and Marguerite largely remained at 13 Pineapple Street. None married, and except for a few mentions, details of their lives in the house are tough to come by. John Jr. perhaps leaves the largest trail due to his service in the Union Army during the Civil War. At the age of 24, in April of 1861, he joined the 14th Regiment New York State Militia, aka the 84th New York Volunteer Infantry, as a private in Company E.

The company’s record shows that he likely would have taken part in battles and skirmishes in Virginia, including the First Battle of Bull Run. He was captured during a skirmish near Gainesville, Va., in August of 1862. He was eventually paroled, although the company record provides no details. He was mustered out in June of 1864.

After his life as a soldier, John Jr. returned to Brooklyn and to Pineapple Street. According to a 1914 obituary he worked with his father as a cooper and was also a volunteer firefighter before taking a job as a clerk at the Register of Arrears office. The 1880 census includes a notation that John Jr., then 39, was partially paralyzed. Whether this was at all related to his war service is unclear. After his death in 1914, sisters Julia, Caroline and Marguerite continued to live at 13 Pineapple Street until their own deaths. Julia died in 1920 and Caroline in 1929, leaving their youngest sister Marguerite the sole Coleman in residence.

It was in the last years of Marguerite’s life that 13 Pineapple began to pop up more consistently in local newspapers, and this is largely due to the rumored ghost.

The Haunted House

In June of 1934, both the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and the Brooklyn Times Union ran slightly different tales of the rumored haunting of 13 Pineapple Street.

The Eagle story involved a little girl being startled by a “spook” appearing in the doorway, but ultimately the stories in both papers unfold as more informative than scary. Neighbors were used to seeing the house tightly shuttered and apparently vacant and were, in the words of the Union, “content to consider the house deserted and, probably, haunted.” They were startled to find activity at the house, and when interviewed the resident of 13 Pineapple seemed equally startled that the house was considered haunted. Renter Theodore Mills, a friend and possibly distant relative of Marguerite Coleman, had been living in the house for years. Mills was a port captain who didn’t return from work until midnight, perhaps explaining why neighbors did not spot much activity at the house.

Mills seems to have had a nice chat with the reporter who turned up at his doorstep and shared some family news. Evidently a falling board had injured Marguerite Coleman in 1928 and she had been living with her niece, Edna Mills Fitch, daughter of Agnes Coleman Mills, ever since. Marguerite, Edna and her husband, Frederick Fitch, were all due to move from Mamaroneck into the house on Pineapple Street as soon as it was spruced up.

Whether a major renovation occurred or not is unknown, but Marguerite did return to the house. She spent her last months at 13 Pineapple Street before her death in March of 1935. Her status as a member of an old Brooklyn family and longtime resident of 13 Pineapple merited obituaries in the Brooklyn papers as well as a brief writeup in the New York Times, which mentioned that she had “refused many offers” for the purchase of the house.

The 20th Century

Marguerite’s death didn’t end the Coleman family’s time in 13 Pineapple, at least not immediately. Her will will left half of her estate to Theodore Mills and the other to niece Edna Mills Fitch. Edna and her husband, Frederick, a salesman, settled into 13 Pineapple for a few years before the house was sold out of family hands in 1937.

The purchasers, young couple John P. Zerega, Jr. and Kathryn Hurst Zerega, were no strangers to the neighborhood. Married in 1933, they settled into Brooklyn Heights after the wedding. While Kathryn Hurst Zerega had grown up in Northern Manhattan, John Zerega’s grandfather had settled in Brooklyn in the late 1840s, founding a successful pasta factory still in business today as Zerega.

John and Kathryn Zerega purchased 13 Pineapple at a time when other families were renovating old houses in the neighborhood. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on this trend in 1938, noting that while the pressure for increased housing was leading to changes in the neighborhood and larger apartment buildings were on the rise, other families were buying “fine old private homes” with plans to have them “modernized and face lifted” until they recalled “the old aristocratic days of their youth.”

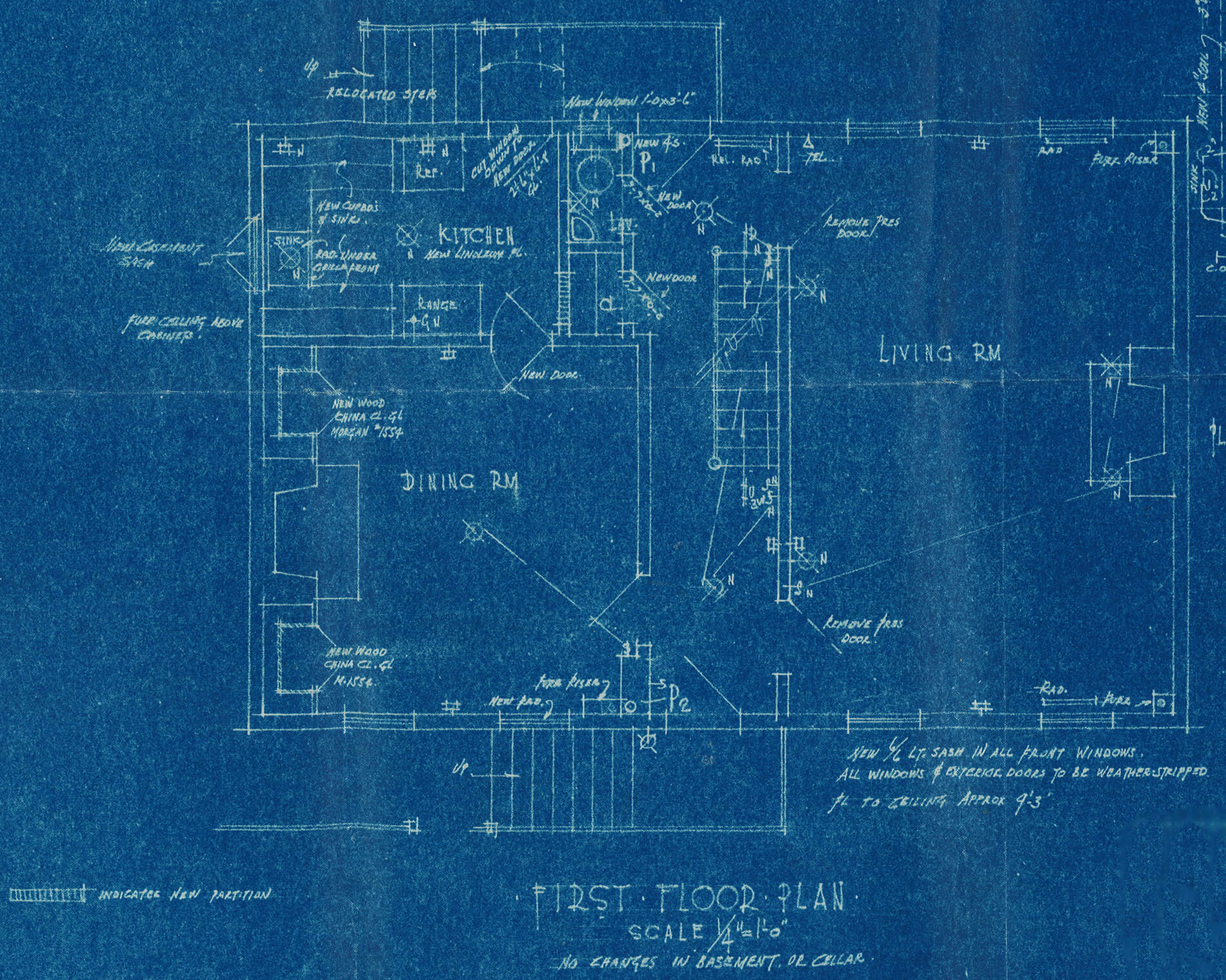

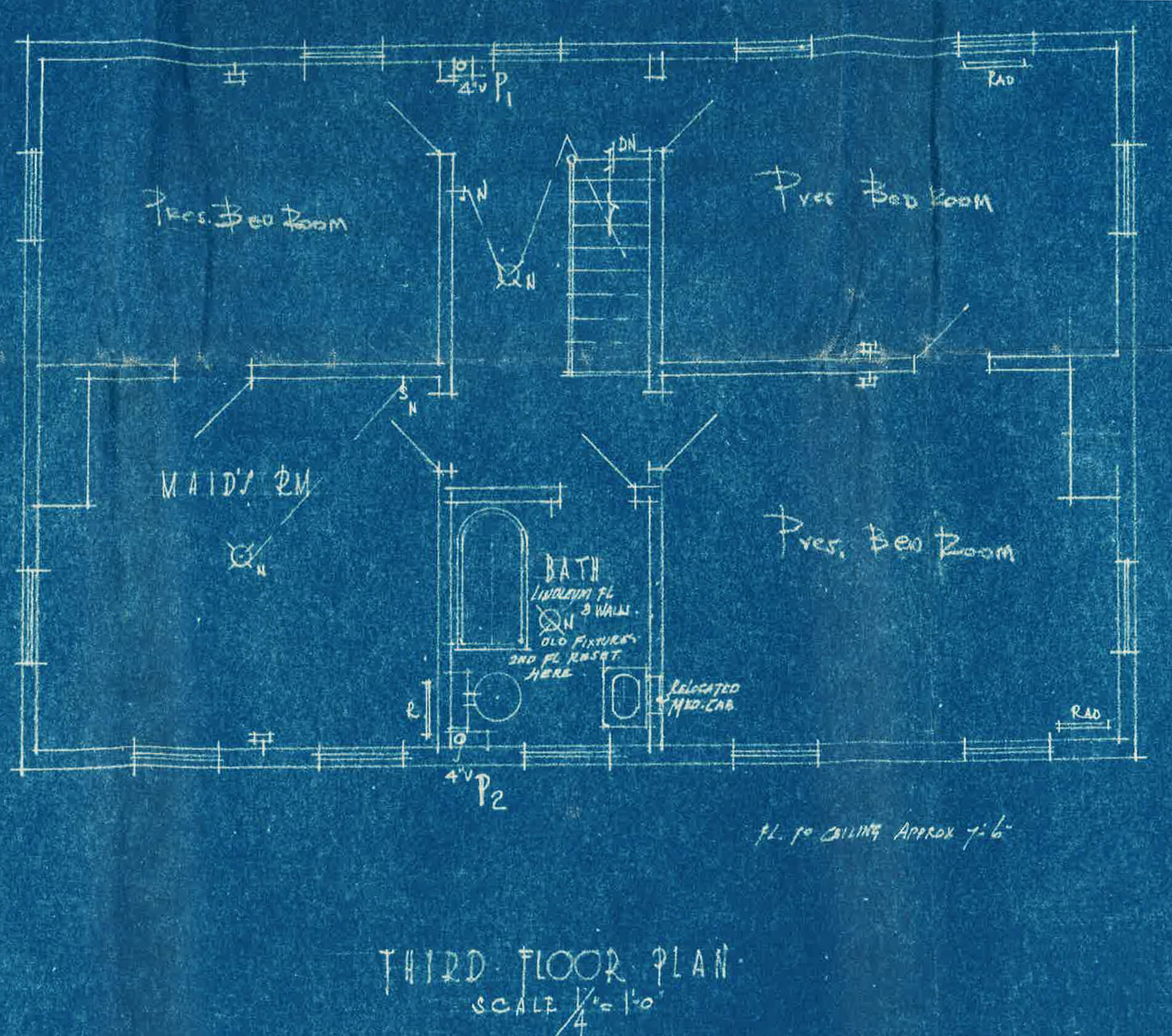

The Zerega family did just that at 13 Pineapple. Before moving in, they hired architect William P. Callahan of White Plains to give the house an overhaul. Some of the paperwork submitted to the Department of Buildings survives and gives an idea of the extent of the changes. Notes on floor plans and the permit application show that most of the work involved upgrading 13 Pineapple Street for modern life. Cabinets, appliances and a new linoleum floor were installed off the dining room to create a modern kitchen. (The same kitchen was later redone, and enlarged with a bay window, in the late 1980s.) An existing bathroom was modernized and additional bathrooms installed on the first and third floors.

The permit filing indicates that the first and second floors were to be painted and decorated, and the floor plans show that at least some Colonial Revival features, like the built-in corner cupboards of the dining room, were introduced at this point. On the second floor, more built-ins were installed in the dressing room off the master bedroom, creating modern closet space.

The plans indicate only minor changes to the facade, including new six-over-six sashes in all the front windows, two new openings in the rear facade, and relocated steps in the backyard. However, historic images seem to indicate the Zeregas did a more substantial “face lift” on the house. The circa 1940 tax photo provides a view post renovation that can be compared with views from 1925 and 1932 at the New York Public Library.

The earlier views seem to show clapboard rather than shingles, at least on the eastern facade. There are shutters installed at all the windows and a columned portico over the stoop. (The latter was probably a late 19th century addition, perhaps appearing at the same time as the new roof.) By 1940 the shutters are gone, the exterior looks crisp and trim with new shingles, the portico has disappeared and a Colonial Revival fanlight has appeared above the front door. The current garage was also probably added during the Zerega’s time, likely around 1946.

John and Kathryn Zerega stayed about 14 years in the house, moving in 1951 to follow the shift of the Zerega family pasta business to New Jersey.

Truman Capote Burnishes the Folklore

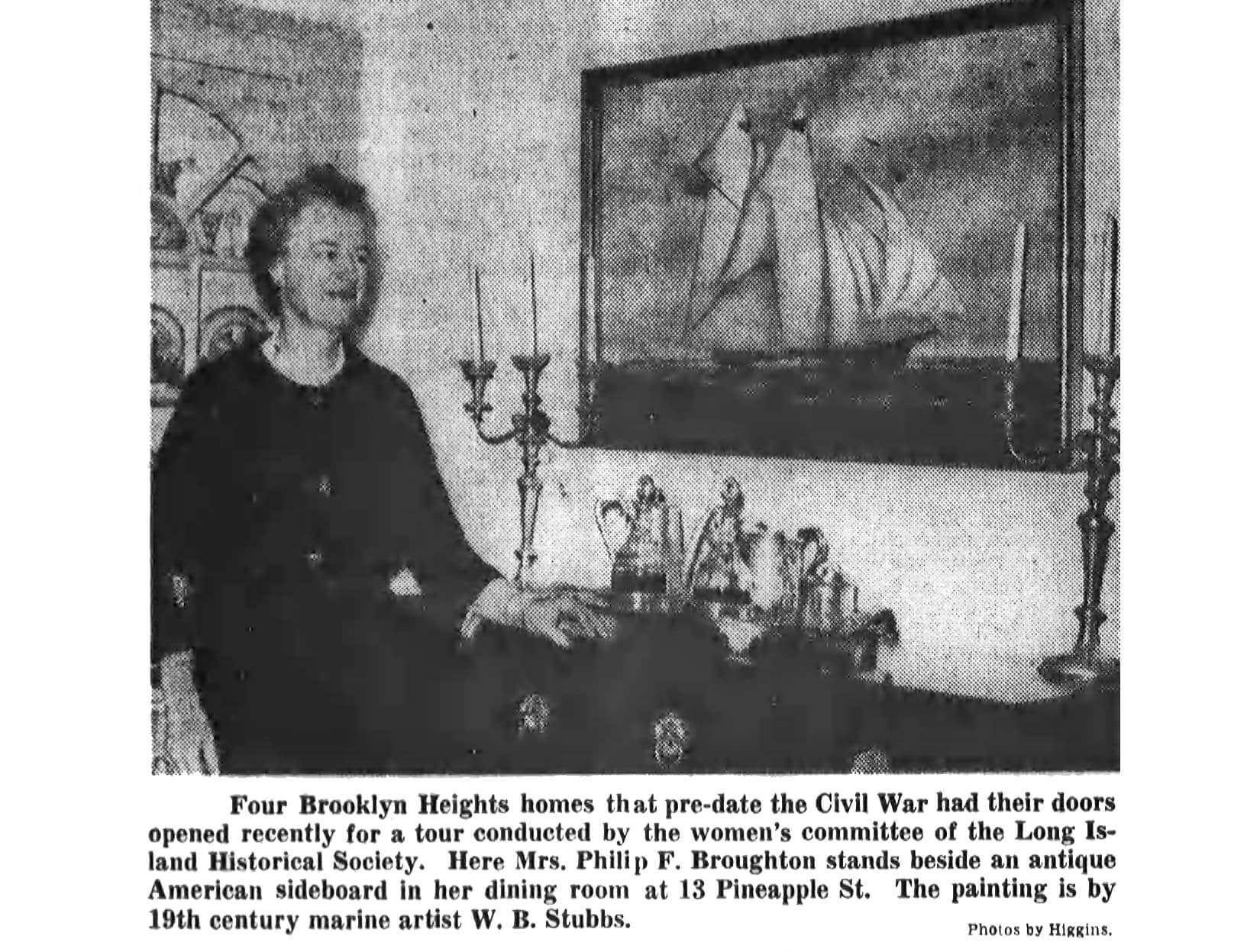

When new owners Philip and Esther Broughton moved in, coverage of 13 Pineapple Street picked up in local papers. The Broughtons were active members of the Brooklyn Heights society set. Their move into the house in 1951 also coincides with education and advocacy efforts around the history and architecture of the neighborhood. The Broughtons, particularly Esther, participated by opening up 13 Pineapple Street for committee meetings, garden tours and historic house tours. Philip was an insurance broker who dabbled in music on the side. He penned the “Forsythia Song” in honor of Brooklyn’s official flower but a work with perhaps a wider audience was a cowriting credit on “Funny (Not Much)” recorded by Nat King Cole in 1953.

Esther was involved in numerous local committees and, if her interviews in local papers are anything to go by, had a true fascination for the history of 13 Pineapple Street. It is during the 1950s and 1960s that much of the folklore surrounding the house appears in print. The stories may have been rumbling around among neighbors but if so, it seems they weren’t put into print until the mid 20th century. Many of these can be traced to Esther Broughton and information she shared with the press and likely her neighbor at 70 Willow Street.

In “Brooklyn Heights: A Personal Memoir” Truman Capote shared the story of a 1790 home of a ship captain, but he never mentioned 13 Pineapple Street by address. Instead, the house he believed to be “the oldest still extant and functioning” in the neighborhood he noted as that of his “backyard neighbors, Mr. and Mrs. Philip Broughton.” With Capote and the Broughtons in close proximity and the Broughtons being part of the social set of Brooklyn Heights, it is fairly likely the couple had shared tales of the house with their literary neighbor. After the story appeared in print, similar tales of the origins of the house were repeated in perpetuity.

If the Broughtons did share tales of the house, where did they get the information? Before moving into 13 Pineapple Street, Philip, a widower with a young daughter, was living at the Hotel Margaret when he and Esther, herself a widow and living on Orange Street, married in June of 1936. The couple settled into 30 Orange Street and their social comings and goings quickly began appearing in local papers.

In September of 1936, the couple held a party at their home and here’s where the tradition of local papers making note of party attendees comes in handy. Appearing on the guest list were Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Fitch. That would be Edna Mills Fitch, the Coleman granddaughter who had sold the house in 1937. That party was just one event where the ladies appear either as guests at the same event or as being involved with the same organizations. Did Edna or other old Brooklyn families share tales of the history of 13 Pineapple Street with Esther Broughton?

We can’t know for sure, but by the late 1950s, when preservation-minded owners were holding Brooklyn Heights house tours to raise awareness, Esther had a story to pique the interest of reporters. In April of 1961, the Women’s Committee of the Long Island Historical Society hosted a tour of pre-Civil War Brooklyn Heights with a look inside Plymouth Church and four houses, including 13 Pineapple Street. A lengthy feature on the tour appeared in the Brooklyn Heights Press and the story Esther shared with tour goers was that 13 Pineapple Street was a Long Island farmhouse built in 1790. It was, according to Esther, purchased by Mr. Coleman in 1830 but “his wife claimed it was too old to live in, so it was remodeled, rebuilt, and the second half added.” The article also mentions that the Broughtons furnished the home with family heirlooms, including some relating to one Captain Broughton, perhaps leading to the ship captain origin story presented by Capote.

It’s difficult to prove how much, if anything, the Coleman family or neighbors passed down regarding the history of the house, but whatever their source, the stories did burnish the house’s reputation and provided terrific fodder for news stories at a time when the movement to preserve the heritage of the neighborhood was at a critical point. The house remained in the Broughton family until the 1980s. It has had just two more owners since.

Since the 1820s each family has left its stamp on 13 Pineapple Street, whether it was changing the appearance or spreading the importance of its history. Perhaps further digging will unearth even more interesting tales of this bit of old Brooklyn Heights.

If you want to see this house to judge its history for yourself you can get your chance this fall when 13 Pineapple Street debuts as the 2019 Brooklyn Heights Designer Showhouse. The showhouse kicks off with an opening party on Wednesday, September 26 and will be open to the public from September 27 through November 3. Proceeds from the event benefit the Brooklyn Heights Association. For more information on tickets and open hours visit the showhouse website. Brownstoner is a sponsor for the event.

Below, some photos of the interior of the house before its showhouse transformation.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- Inside One of Brooklyn Heights’ Oldest Houses, 24 Middagh, and Its Mysterious Past

- The Federal Style: An Architecture for a New Nation, 1785 to 1830

- Huge Heights Federal House With Parking, Seafaring Past Asks $10.5 Million

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment