The Life and Times of Park Slope's Singular Montauk Club

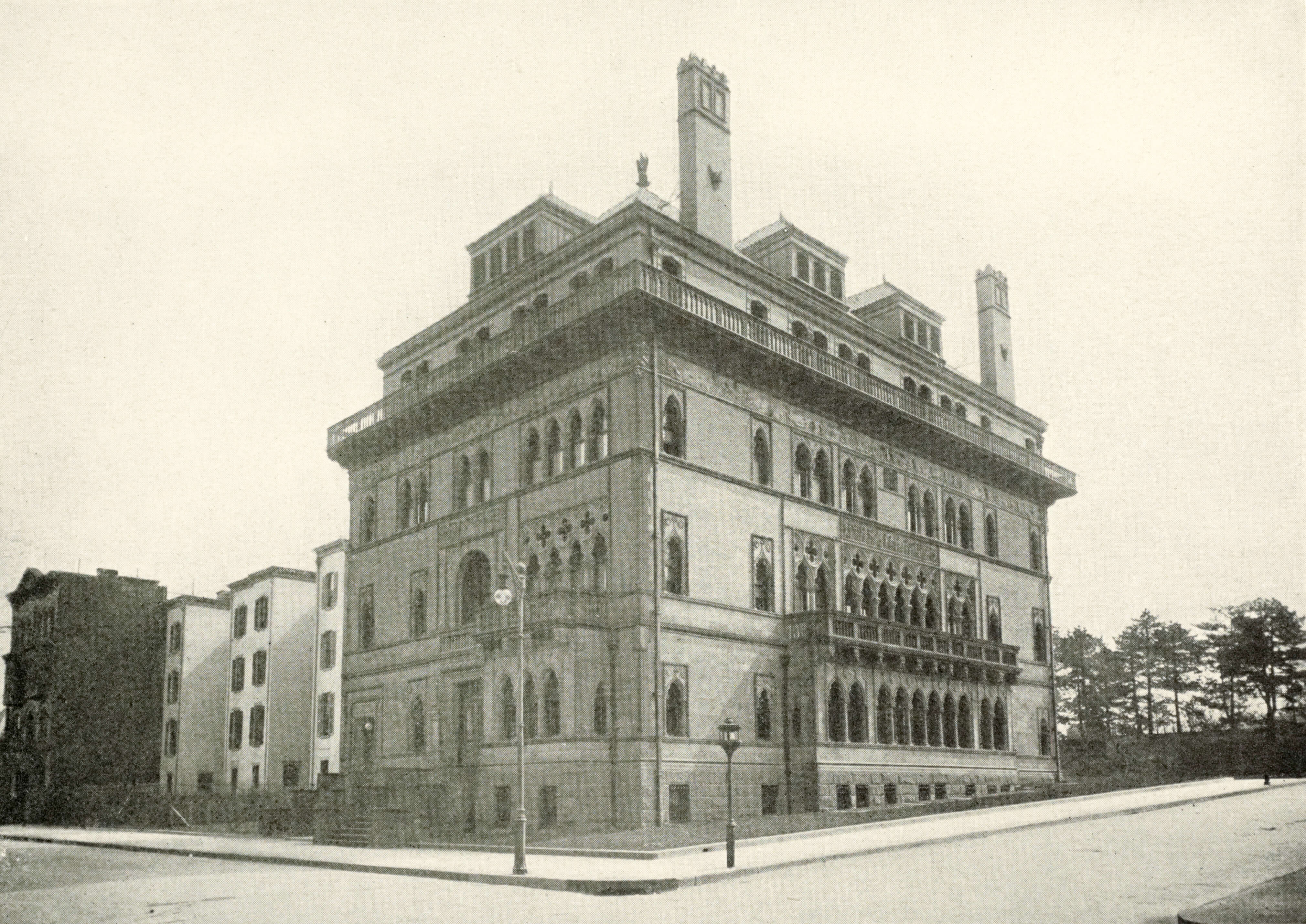

Noted 19th century architect Francis H. Kimball designed a fanciful Venetian Gothic Palace with American motifs for Brooklyn’s popular club.

The building’s brownstone and terra-cotta details depict American flora and fauna

Late 19th century Brooklyn was a city basking in the glories of the Gilded Age. Taking their cue from the English gentry, wealthy New Yorkers embraced the creation of posh private gentlemen’s clubs. Here, a man could be waited upon with no family demands on his time, and most importantly, hang out with his peers, perhaps wheeling and dealing, or just sharing a fine whiskey, a meal, or a poker game with the boys. The more elite the club, the more important the man.

Brooklyn had several exclusive men’s clubs. The oldest was the Brooklyn Club, located in the Heights and founded in 1867. It was a who’s who of Brooklyn’s upper crust, many of whose names grace our streets. Other clubs followed, opening in other upscale neighborhoods as development pushed outward.

Park Slope’s growing popularity spurred the creation of the Carleton Club, located at the corner of St. Marks and 6th Avenue. It was founded in 1881 by a group of men who felt their neighborhood had wonderful homes but was lacking in amusements. Their club was soon filled.

In 1888, a group of Carleton Club members decided to split off and start their own club. By this time, 8th Avenue, the surrounding named streets and Prospect Park West were becoming a wealthy enclave of freestanding mansions and expensive attached townhouses.

The group of about 25 men incorporated as the Montauk Club in 1889. The name had no real meaning other than to reference Brooklyn’s “exotic” Native American past. The group rented a brownstone at 34 8th Avenue and opened the membership. In a matter of months, they had 300 members. The brownstone was not going to be large enough.

Local real estate man Leonard Moody found a suitable plot of land for the club just down the street at 25 8th Avenue. They paid $40,000 for the large site and held a competition for a designer. The winner was noted architect Francis H. Kimball.

Francis H. Kimball — an Architect for His Time

Francis Hatch Kimball was born in Kennebunk, Me., in 1845. At the age of 14 he apprenticed to a builder for several years before joining an architectural firm in Boston. He was chosen as the supervising architect for Trinity College in Hartford, Conn., during which time he was sent to England to study with Trinity’s British architect, William Burgess.

Burgess instilled his love of Gothic architecture in Kimball, lessons that would influence many of his buildings. When he came back to New York in 1879, he opened his practice with an English partner, Thomas Wisedell. The two designed churches and theaters until Wisedell’s death in 1884. Kimball continued on his own. In 1886 he designed Clinton Hill’s French Gothic-style Emmanuel Baptist Church for oilman Charles Pratt.

Kimball fell in love with architectural terra-cotta. Its use as a decorative element could mimic carved stone, enabling him to create ornament that would not be economically possible in any other medium. He used terra-cotta trim lavishly in most of his buildings, including the Montauk Club, a group of row houses on 122nd Street in Harlem, and the Corbin Building at 11 John Street in Lower Manhattan.

Kimball has been called the “father of the skyscraper” for his work in New York’s earliest tall buildings. He developed a system of caisson foundations that became the basis of skyscraper construction. His Manhattan Life Insurance Company building at 64 Broadway, demolished in 1964, was the first skyscraper to be built with a full iron and steel frame set on pneumatic concrete caissons.

Kimball’s other buildings include the Rhinelander Mansion on Madison Avenue, now home to Ralph Lauren, the Empire Building, and the Trinity and United States Realty Buildings, all landmarked. All, including the Corbin building, have strong elements of Gothic design or are lavishly decorated in terra-cotta trim — or both.

The Montauk Club’s Design

Francis Kimball designed the Montauk Club in the Venetian Gothic style. The building is based on Venice’s Ca’d’Oro, today a museum on the Grand Canal. The Venetian elements can be seen in the loggias and windows, as well as the general shape of the building. While Kimball was in England, he was highly influenced by the popularity of the Venetian Gothic and Renaissance style — itself an amalgam of Middle Eastern and Gothic forms.

The result is a building uniquely late 19th century American, emphasized by the Native American theme in the ornamentation. Where else would one find a Venetian palazzo with Gothic tracery, Victorian stained glass, and columns with Native American faces as capitals? It’s all wonderfully unique and beautiful.

Kimball put elaborate windows and ornamentation on three sides of the building. He left the north side of the building relatively free, expecting the club to expand in the future with an addition. The remaining three sides are a study in light and the use of contrasting solids and voids. The Gothic tracery, the stained glass, the loggias and oriel window bays, plus the pale red brick building itself, all add up to one of Brooklyn’s most beautiful buildings.

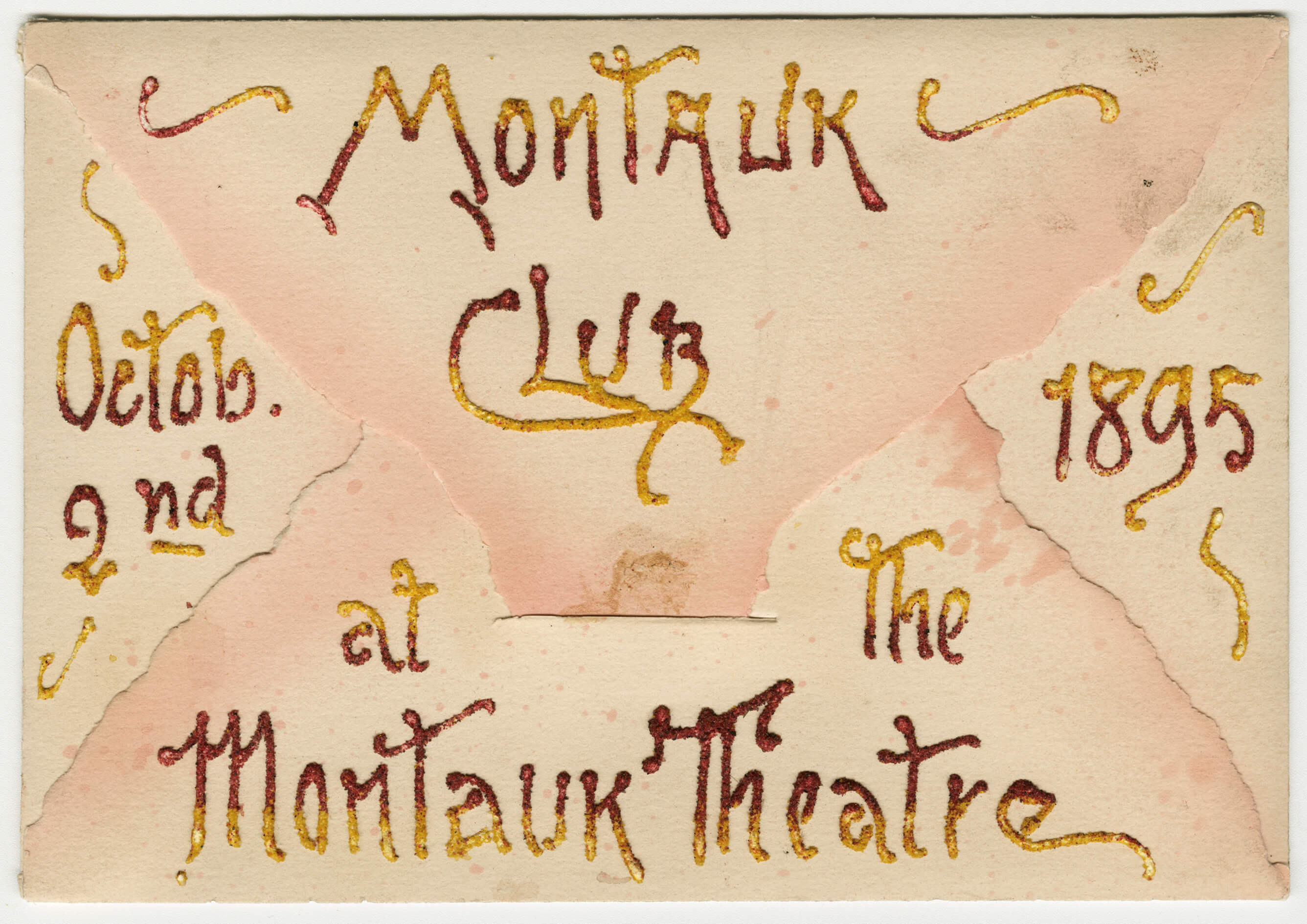

The groundbreaking for the Montauk Club took place on October 2, 1889. The club opened for business in 1891. A terra-cotta frieze depicting the laying of the cornerstone (with the wrong date) greets visitors on 8th Avenue. Controversy abounded when it was revealed, as no one thought the images were very flattering, especially those who were depicted. But despite complaints, the frieze remained.

Clubbing at the Montauk

Although many of the club’s members lived in Park Slope, the Montauk Club attracted wealthy members from all over Brooklyn. They included the city’s mayors and borough presidents, inventors and industrialists, lawyers, judges, bankers and politicians. Charles Pratt was one of them, which didn’t hurt Kimball’s chances of winning the competition. Many of these men belonged to other clubs, but the Montauk was the most prestigious.

For a club catering to bigwigs and large egos, the Montauk also was quite progressive. Women could not be members, but wives were given their own dining room upstairs. Kimball designed a ladies’ entrance to the left of the main entrance on 8th Avenue. The ladies went up a separate staircase to their own elegant rooms, never interacting with men.

The club was also open to new cultural attractions. In June of 1889, while still at 34 8th Avenue, the club had a Chinese feast, prepared by Manhattan’s most famous Chinese chef, Sue Gee. Chinese food was still a novelty and was not seen as fit food for upscale Westerners. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote about the event with an article entitled “Heathen Fare Will Be on the Tables of the Montauk Club.” The evening was a great success, and probably helped popularize Chinese food in the city.

Unusually, the Montauk was not a political club and accepted both Democrats and Republicans. They also did not have a restrictive policy towards Jews, unlike many Brooklyn institutions. Money and connections were the main indicator of membership.

Club members enjoyed the first floor, which contained a parlor, library and smoking room. The doors between them could recess, opening up the entire floor into one large gathering space. The second floor had a billiard room, card rooms and other reception spaces. The third floor contained the main dining room as well as the separate ladies’ parlor and dining room. The fourth floor offered hotel-style lodging rooms for six lucky members who shared a common bathroom. The main kitchen was in the basement, with dumbwaiter service throughout the building. The basement also had a bowling alley.

As Time Goes By

The Montauk Club was extremely popular for years. Most of Brooklyn’s elite belonged to it. Local and national politicians were invited to speak over the course of the 20th century, including presidents McKinley, Hoover, Eisenhower and both John and Robert Kennedy. New York Governor Hugh Carey was a longtime member.

The club was much loved but so popular members complained the long-term bedrooms were never vacated and the club lacked a large ballroom or hall. It was thought an addition would be built on the south side, as per Kimball’s plans, but one never was.

The club also had a few scandals of the embezzling kind. These were called “defalcations” in their day. The first defalcator was Nathaniel T. Houghton, who was treasurer and bookkeeper for the club in 1894. Over the course of a couple of years, he slowly skimmed off more than $5,000 of club money. That would be the equivalent of almost $138,000 today.

When the theft was discovered, he left his family behind and took off to Ohio. The management and membership of the club were dumbfounded, as Houghton was well liked. He returned to New York and was arrested, upon which time he tried to negotiate with the club to pay back the money. He pled guilty at his trial, still trying to negotiate. Many club members signed letters of support and told the judge that Houghton had been offered a job in Ohio if he was shown leniency.

The judge wasn’t having it. In a forceful and progressive declaration, Judge James A. Murtha said, “Because a man is brought up in good surroundings and is offered no incentive to steal on account of poverty or hunger, I am expected to open the prison doors and let him go free? Yet a poor fellow who is brought up amid every temptation and knows no better than to steal is sent to prison without the care or petition of anyone.” He sentenced Houghton to the maximum of three years.

In 1916, Wall Street broker Christopher Wagner, who was rooming on the top floor of the club, answered a knock on his door. It was a detective, there to arrest him for embezzling from his company.

Wagner, still in his underwear, excused himself by saying he was going to the bathroom to get dressed. He crawled out onto a ledge and dove, sailing past guests in evening dress dining below. He hit the ground so hard he broke the pavement. The suicide was his second attempt. Only days before, a maid at the club woke him up because she smelled gas in his room. Fortunately, nothing like that happened again.

Despite the occasional scandal, the club remained popular. But even with membership at 701 in 1949, to stay open the Montauk had to change its rules of membership, its dues policies, and the amenities of the club. As Brooklyn moved from the Gilded Age through the Jazz Age and the Space Age, clubs like the Montauk became quaint reminders of the past.

The club survived wars, the Depression and Prohibition, no doubt with more than one secret liquor stash, but was almost done in by the post-World War II exodus to the suburbs. The club’s membership dwindled and it was forced to close most days and open only for lunch and special events.

But as Park Slope redeveloped as one of the most popular and exclusive neighborhoods in a revitalized Brooklyn, interest in the club grew. A new generation of managers and members made great changes. To subsidize the club, the basement and top two floors were sold as condominiums. The former ladies’ entrance is now the private entrance for those fortunate to live in such splendid surroundings.

The Montauk Club now occupies the ground and second floor of the building. It is a popular venue for weddings, parties and meetings. As in the days of old, club members can retreat there and luxuriate in Venetian Victorian splendor, albeit slightly run down and comfortable, like any good club. Only now everyone is welcome as a member, and all can use the front door.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2018 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- Producer Charles Hobson Remembers ‘Inside Bedford-Stuyvesant’ on Its 50th Anniversary

- Greenpoint’s Astral Apartments: A Building Ahead of Its Time

- Striking Art and Playful Inventiveness Create Comfortable Clinton Hill Home

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment