Historic St. John’s College Campus in Bed Stuy to Reopen as Apartments

An adaptive reuse project will save an important part of Bed Stuy’s history and create more than 200 mostly market-rate apartments.

An existing wing of the campus on the corner of Lewis Avenue and Hart Street. Photo by Susan De Vries

The eye-catching St. John’s College, which takes up a quarter of a block on Lewis Avenue between Willoughby Avenue and Hart Street, will shortly reopen as an apartment complex after an impressive adaptive reuse project converts the campus to residential units.

While the majority of the historic buildings remain unaltered on the exterior, the oldest wing, which ran along Willoughby Avenue, was demolished and is being replaced by a similar new building that has topped out.

A housing lottery has recently opened for the entire project, which has taken the address 788 Willoughby Avenue. St. John’s College previously had the address of 75 Lewis Avenue.

The first wing of the Romanesque Revival pile, College Hall, opened in 1870 on the corner of Willoughby and Lewis. The rest of the buildings were in place by 1872. Designed by architect Patrick Keely and built by the Catholic Church, the four- and five-story red brick buildings surrounding a central courtyard are notable for their multicolored slate mansard roofs, arched windows, a round corner tower, a domed cupola, and a two-story-high bay window and entrance canopy on Lewis Avenue. The college relocated to Queens in the 1950s.

Since then, the Bed Stuy complex has housed an array of religious schools and service organizations, including the New Horizons Adult Education Center. Plans to convert the complex to rental apartments have been in the works since at least 2015, but until recently little seemed to be happening and the property’s future appeared unclear.

Despite its impressive architecture and significance in Bed Stuy’s history, the campus is not landmarked, meaning the developers could have demolished the entire structure. The decision to adapt the buildings for a new use may have been made because they are already larger than what could have been built under existing zoning. As well, the site was deemed eligible for the National Register in 2020 and therefore could potentially receive tax credits for adaptive reuse through the National Park Service.

The conversion to apartments was facilitated through a deal between a private developer and the Roman Catholic Church, which still owns the site and the massive stone St. John’s the Baptist Roman Catholic Church next door at 333 Hart Street. (The latter is still operating as a church, its online event calendar shows.)

According to city records, the Roman Catholic Church leased the site that includes the college campus but not the church to 75 Lewis Avenue LLC, with signatories Matthew and Frank Linde of Property Resources Corporation (or PRC), in 2018. The documents show the LLC paid $14.193 million for the ground lease, set to expire in 2067. The deal included air rights from the church building so the developers could increase the floor area of the new building, documents show.

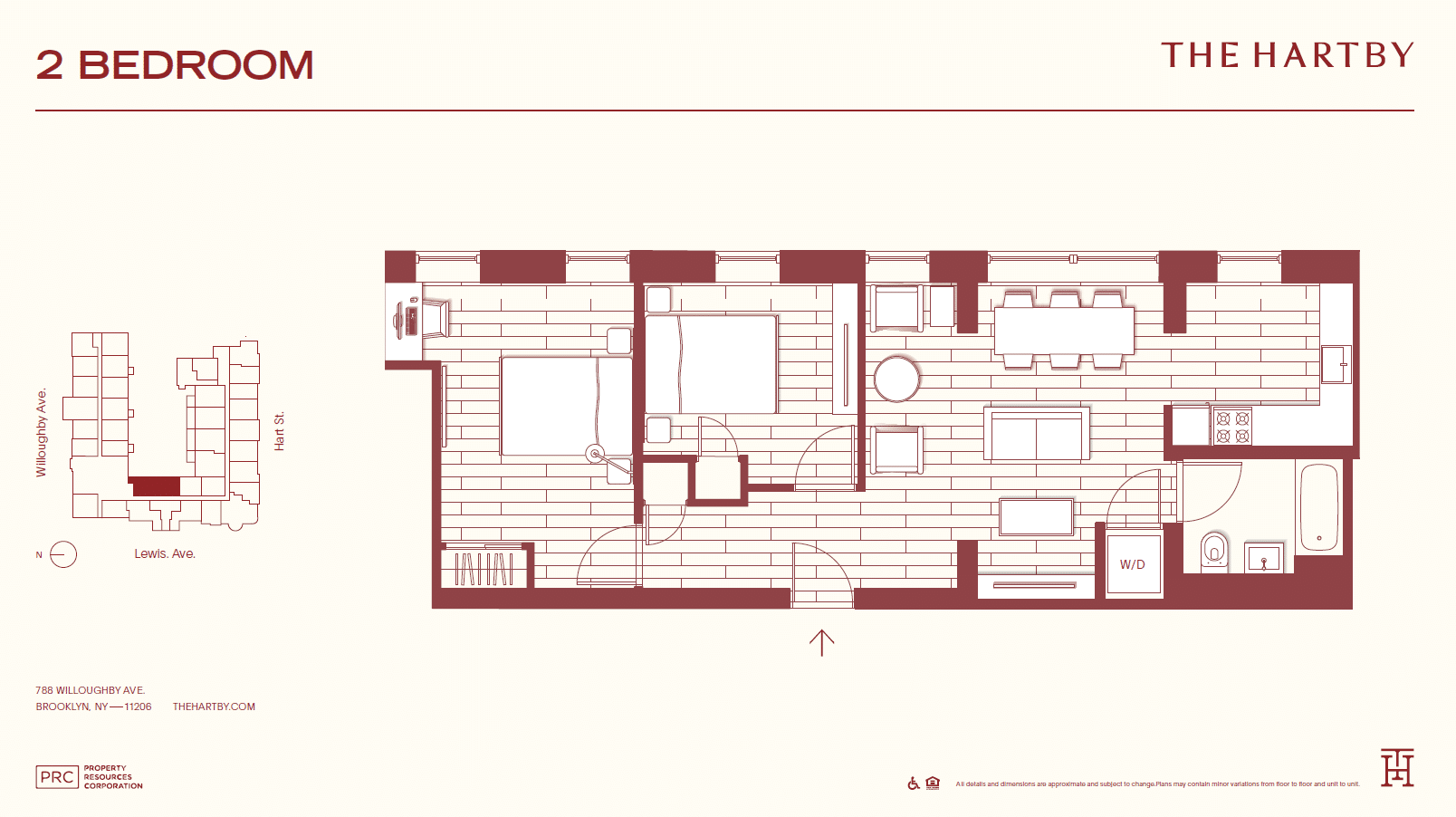

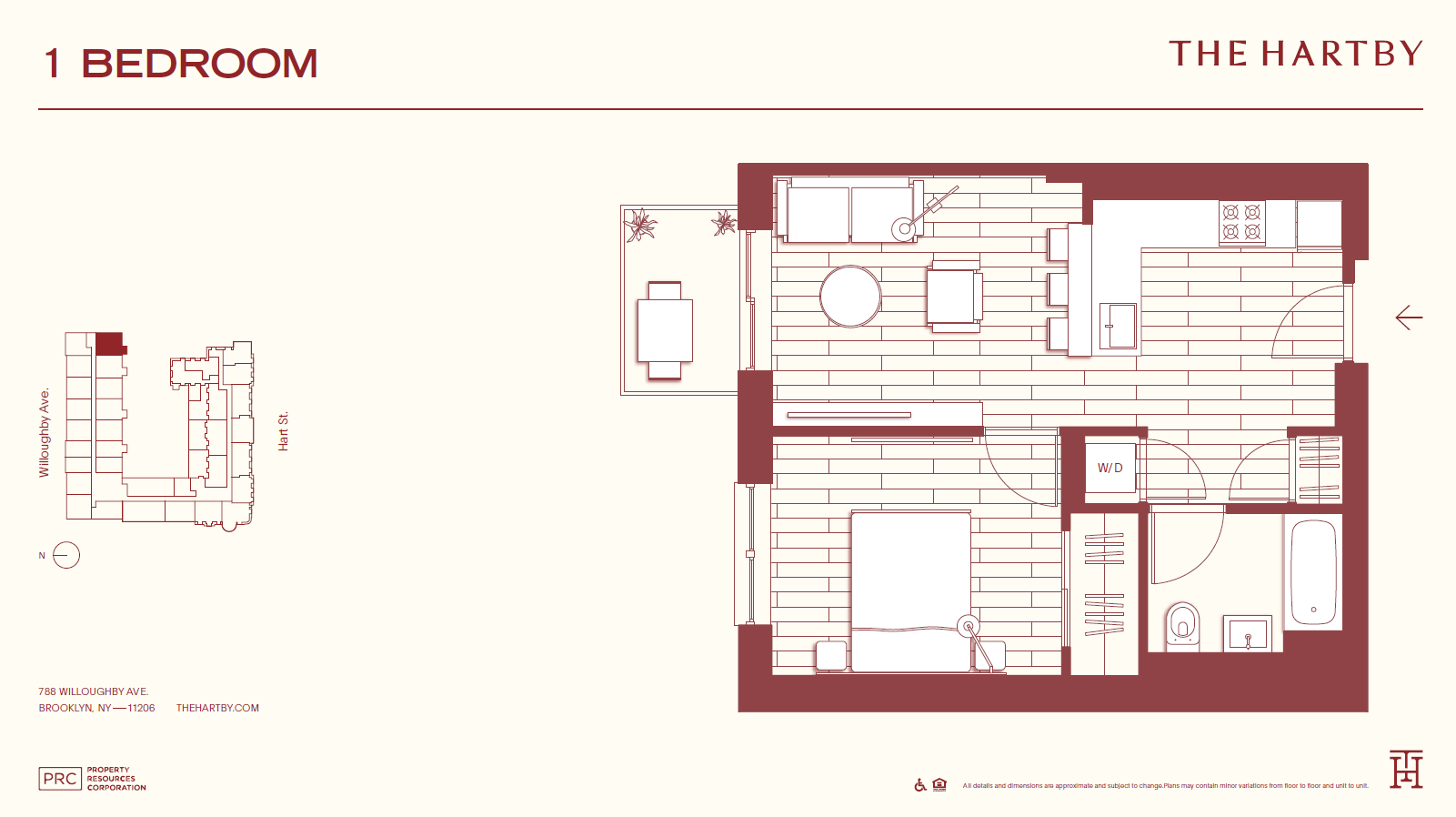

The new wing along Willoughby Avenue will have eight stories, and altogether the conversion will create 205 studio, one-, and two-bedroom apartments, according to Department of Buildings permits and the architect’s website. Woods Bagot Architects is behind the design.

Renderings show the new wing will be six stories, not eight, and will closely resemble the one it replaced in coloring, form, and height, although the details will be modern. Its mansard roof, brick color, and window placement match those of the other buildings. Recessed brickwork in a checker pattern will ornament the under-window spaces and corners of the new build. Protruding brickwork will create a striped effect on the lower floors, where a modern entrance canopy will rise two stories.

A recent visit to the site revealed College Hall has been razed, and the replacement building has topped out. While the new wing is completely covered in scaffolding and netting, some of the brick detailing around the windows is visible.

The remaining administrative building, which sits in the middle of Lewis Avenue, and seminary wing, which runs along Hart Street, have emerged from scaffolding and look as grand as ever. They are, however, still behind a green construction fence.

The housing lottery for the 48 income restricted and rent stabilized apartments in the revamped complex, now dubbed The Hartby, recently opened for households earning 130 percent of Area Median Income, or $85,543 to $218,010 a year. At that level of AMI, allowed by the 421-a tax program from which the development benefits, rents for lottery units are typically close to market-rate prices. Studios in this lottery go for for $2,495 a month, one-bedrooms for $2,795, and two-bedroom units rent for $3,939.

Renderings show units with mostly white, minimalist, somewhat generic interiors, enlivened with interesting historic features. These include rounded corners and bays with windows, a wood-paneled wall surrounding a large round window, and arched windows.

Floor plans show a 409-square-foot studio, 526-square-foot one-bedroom, and 855-square-foot two-bedroom. Building amenities include a roof terrace, parking, electric car charging stations, an attended lobby, business center, gym, party room, shared laundry room, bike storage, and dog washing station.

The complex is set to open sometime this fall.

Related Stories

- This Mansard Roofed Romanesque Revival Pile Was a Bastion of Higher Education in Bed Stuy

- Walkabout: Saving St. John the Baptist Church

- Pre-Civil War Gothic Revival Church on Bed Stuy’s Willoughby Avenue Demolished as Locals Look On

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

I’m extremely pleased that the majority of the complex was saved. My mother taught here years ago when it was a Catholic elementary school. They only used part of the building at that time. It’s a shame they didn’t save the oldest part of the building, though. And I think that converting it into housing was the best use possible, and people have been advocating for that for a long time. BUT… NO ONE living in that neighborhood can afford the “affordable” units, or the market rate ones, which aren’t much more monthly rent. They are just creating an oasis of wealth within a desert of those who have much less. That’s hardly good city planning. On top of that, could they make those units less boring? OK, they saved some of the window details, but otherwise, they seem to be nothing but cheap looking generic sheetrock boxes with the inevitable open plan. I’m pretty sure the original Victorian classrooms had architectural details that could have been re-used – some wainscoting, floors, casework. I’m grateful they didn’t tear the entire thing down, but it should have been landmarked ages ago, as well as on the National Register. I’m praying that the Catholic Church doesn’t decide one day to sell off St. John the Baptist Church. That building is a masterpiece and an important part of Bedford Stuyvesant and Brooklyn’s religious history.