Brownstone Revival: The Rebirth of the Brooklyn Townhouse

Still going strong today, a back-to-the-city movement wasn’t for whites only.

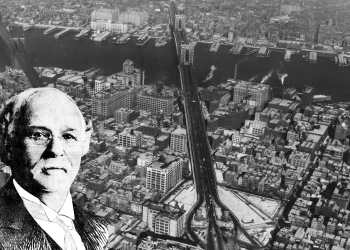

Houses along Berkeley Place, including No. 211, where someone is maintaining a window, in 1973. Image courtesy of the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission

For many, the brownstone is the quintessential symbol of Brooklyn, as much an icon as the Brooklyn Bridge. Yes, other boroughs also have attached masonry row houses, but the Brooklyn brownstone beats them all.

As the urban centers of the United States grew, so too did row-house neighborhoods, their housing based on centuries-old European forms. People of every income level poured into Brooklyn, all seeking a better life and the creature comforts being touted everywhere. Brooklyn was branded the “city of homes and churches,” as good a catchphrase as any invented today. Brownstone Brooklyn’s neighborhoods grew by leaps and bounds.

Fast forward, things began to change during the 1920s and into the Depression years. Brooklyn’s wealthy set began their exodus from their Brooklyn townhouses to new luxury apartment buildings or the upscale suburbs of Westchester and Long Island.

There they could live in pretty much the same splendor as before, but upkeep was less, live-in servants were becoming a thing of the past, and it was all on one floor. In the Jazz Age, the new, modern buildings were a welcome change from the dark wood and old-fashioned styles of Victorian architecture. For these people, brownstones were passé.

During World War II, Brooklyn became the leading manufacturing city in America for the war effort. But in the decades after the war, high-paying union factory jobs began to move to the South and overseas where labor was less expensive.

The industrial exodus and a rise in white collar jobs, GI Bill benefits, cheap mortgages for whites, and redlining and racial segregation created white flight, while Blacks and Hispanics had no choice but to stay in the city.

African American and Hispanic buyers and renters were steered into the redlined neighborhoods of central Brooklyn. They formed a vast amorphous minority neighborhood called Bedford Stuyvesant that sometimes included all of Bed Stuy and Crown Heights as well as parts of modern-day Clinton Hill/Fort Greene, Bushwick, Prospect Heights, and Park Slope.

With sections of extreme wealth and extreme poverty on either end of the spectrum, most of Brooklyn’s brownstone neighborhoods were working and middle class. This included the “largest ghetto in America” called Bedford Stuyvesant. They may not have been modern or new, but brownstones were home to millions. The families who lived in them may have had the whole house, or they may have lived in an apartment or a room. Extended families lived together. They were owners and renters. And eventually, these row houses would become fashionable again.

While many were doing their best to escape Brooklyn, a few preferred it. In the early and mid 20th century, artists, writers, musicians, and entertainers spread throughout the borough, some clustering in Fort Greene and Brooklyn Heights. They included Marianne Moore, Richard Wright, W.H. Auden, and Carson McCullers. Broadway set designer Oliver Smith purchased an historic home on Willow Street and rented to the likes of Truman Capote, who liked to tell posh visitors that he owned the entire house.

A few of the old families lingered even as many once-grand houses became SROs. In the 1950s, groups of young white professionals including people in the arts, law, education, and finance began buying row houses. They were drawn to the Heights and its tree-lined streets and elegant row houses because they were affordable and a short commute from Manhattan on an expansive system of subway lines. They also discovered that they liked the lifestyle.

The Heights was an enclave surrounded by industry to the east and west. The less well off lived near Atlantic Avenue and where the BQE and its ramps and lower Cadman Plaza are now. The nearby waterfront was busy, with sailors and longshoremen crowding into neighborhood bars. The commercial core around Borough Hall and downtown completed the borders of the neighborhood.

But inside the circle, on tree-lined streets, artists and teachers could live next door to stockbrokers, lawyers, and the remaining rich old guard. They were white, liberal, comfortably middle class, and converts to old-house living. They renovated their homes and joined or started community organizations. They wanted to preserve the grand 19th century feel of the neighborhood. Some were eager to see the urban landscape change for the better and envisioned a truly mixed neighborhood, transcending class and race.

Robert Moses had plans for the neighborhood that included running a highway through it and razing parts of the Heights for high-rise housing. Unexpectedly, he encountered a group of organized, highly educated, and connected new residents ready to fight for their adopted neighborhood, as Suleiman Osman recounts in “The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn: Gentrification and the Search for Authenticity in Postwar New York.” They hadn’t purchased their brownstones and contributed their money and sweat equity only to see Moses cut a highway through their blocks like he would in working class Red Hook. They joined ranks with the remaining old wealth concentrated on the best blocks, and after much effort were able to stop the highway and advocate for the construction of the Promenade.

During this period, they were also fierce supporters of a proposed historic preservation law, and enlisted architects and historians like Clay Lancaster to inventory and categorize the blocks. His 1961 book, “Old Brooklyn Heights: New York’s First Suburb,” was a seminal work. The destruction of Penn Station and the proposed demolition of Grand Central Station, along with the Heights fight, led to the creation of the Landmarks Preservation Act of 1965. Brooklyn Heights was the first historic district to be designated under the new law. These Brooklyn Heights homeowners were the vanguard of a brownstone revival movement.

Thanks to print media and word of mouth, more upwardly mobile young white professionals and creative people and their families began moving to Brooklyn. By the late ‘60s, the Heights was becoming more and more expensive with less inventory, so would-be homeowners began branching out. On the other side of Atlantic Avenue was another old 19th century row house neighborhood, with similar architecture and its own history.

To separate it from Red Hook and the rest of lower-income South Brooklyn, these new people named it Cobble Hill after a Revolutionary War fort on a hill that overlooked the harbor. Carroll Gardens and Boreum Hill were other new 20th century neighborhood names and newly desired neighborhoods. Some would-be buyers were also eyeing Fort Greene and Park Slope.

Of course, the arrival of these new homeowners was not a linear progression from neighborhood to neighborhood. Buyers were venturing into many brownstone neighborhoods in the ‘60s and ‘70s. It became a citywide, national, and global phenomenon. New homeowners were moving to Manhattan’s Upper West Side, Greenwich Village, and Chelsea too, drawn by reasonable prices, availability, and a newfound interest in city living and return to a more genteel way of life. They were writing books, interviewed in magazines, and hailed as the “new pioneers.”

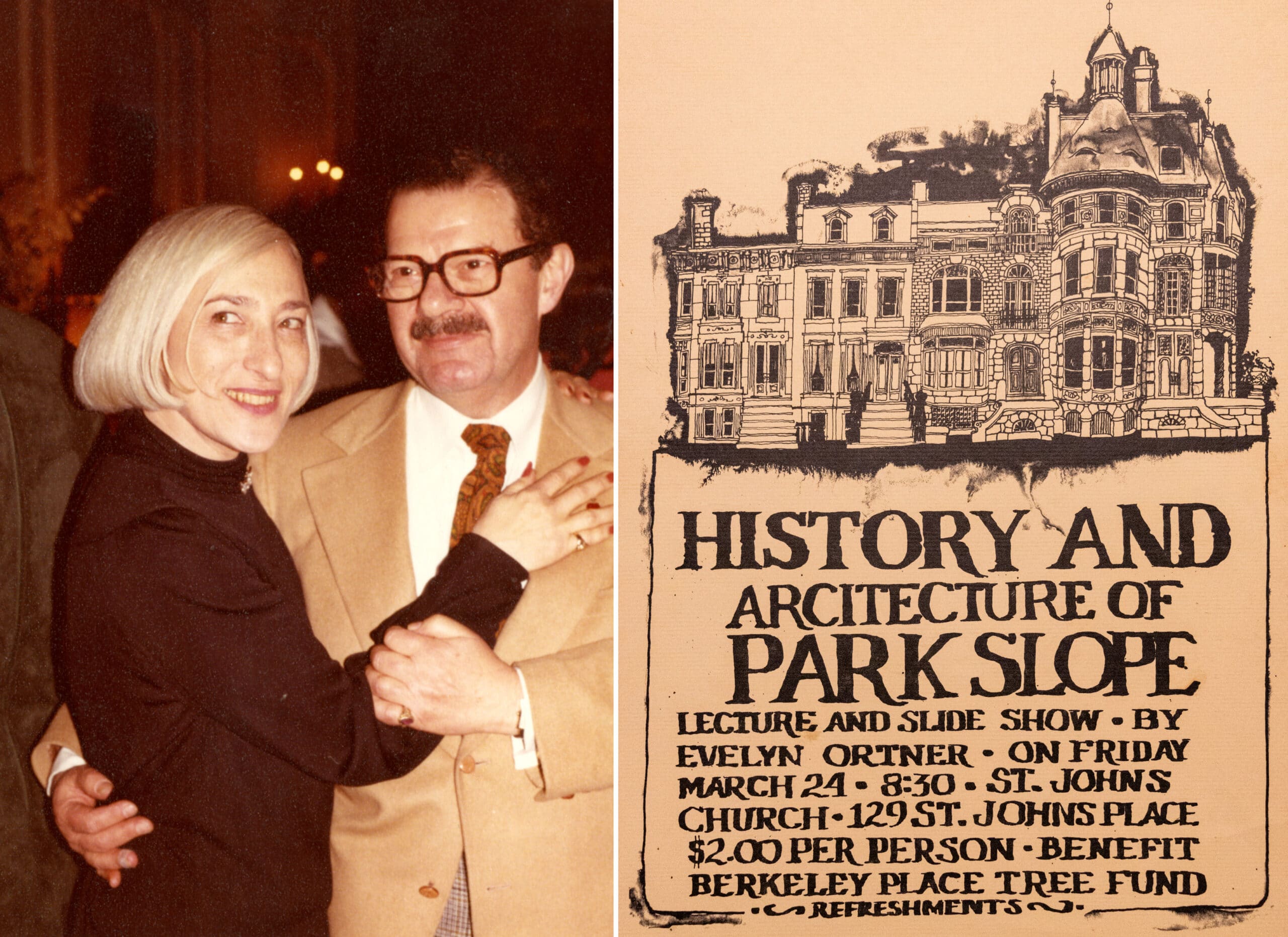

In 1963, Everett Ortner and his wife, Evelyn, bought a brownstone on Berkeley Place in Park Slope. He was an editor at Popular Science magazine; Evelyn was an interior designer. They were among the 1950s wave of Brooklyn Heights residents, spending the first 10 years of their marriage in an apartment in one of the grand townhouses. Like many, they were drawn to Park Slope after being priced out of the Heights.

They arrived in Park Slope because of Robert Mackla, a lawyer who grew up in Park Slope and moved back in the 1950s after a tour of duty in Korea, as the Ortners recalled in an oral history for the New York Preservation Archive. He became a trustee in the local business association, the South Brooklyn Board of Trade. Park Slope back then had been more or less written off as a neighborhood in further decline, like much of Brooklyn. Much of the housing stock was owned by absentee landlords and there were a lot of abandoned and failing buildings. When a passenger jet crashed into a corner building on Seventh Avenue and Sterling Place in 1960, one newspaper described the scene as a “plane crash in a rundown neighborhood near a park.” Mackla was determined to change that.

He convinced the board of trade to adopt a new name, the Park Slope Civic Council. The group was instrumental in the establishment of individual block associations and was a vital part of convincing the city to build P.S. 321. They also led the fight to preserve and restore Prospect Park, which hadn’t seen any real attention in decades and was considered dangerous.

One of Mackla’s farthest reaching efforts was conducting walking and house tours in Park Slope. It was during one of these events that the Ortners saw the house in which they would spend the rest of their lives. Evelyn immediately saw the possibilities in the original fine woodwork, floors, and six fireplaces, as well as the tall ceilings, Lincrusta wallpaper, and generous garden space. They already had a collection of Victorian furniture. The house needed a lot of work, as it was cut up into six apartments, but it was still gorgeous. They went to their bank for a mortgage and were roundly rejected.

That block of Park Slope was redlined. Most of Brooklyn’s historic neighborhoods were considered by lenders to be a poor investment. They had out-of-fashion, old, and declining housing stock chopped up into apartments with kitchenettes, too many vacant buildings, and too many minorities and poor people. Banks wouldn’t give the Ortners a mortgage even though the couple had a decent income, good credit, longevity in employment, and were clearly able to keep up on payments. They went to 12 different banks before finding one that would give them a mortgage. They experienced what Black and other minority would-be buyers had been experiencing in redlined neighborhoods every day since the 1930s.

After getting settled, the Ortners became two of Park Slope’s most powerful advocates. Middle-class white homeowners were still moving out to the suburbs en masse, and slumlords were walking away or selling, so there was a large inventory of buildings that needed new owners. Both Everett and Evelyn were tireless promoters of their new neighborhood. She and other members of the PSCC continued the house tours, highlighting houses that were for sale.

They sought out friends and met other like-minded people on the tours and persuaded them to join them in the Slope. One of those recruited was Clem Labine, a writer, who purchased a house a block away. For many years, Clem’s house, which he meticulously restored, was a highlight of Park Slope house tours. His enthusiasm for old houses led him to create Old House Journal, which began as loose-leaf newsletters with punch holes that subscribers would collect in three-ring binders. For several years, it was the only place to find information on historic home repair or source products. Now a glossy magazine, it’s still going strong after more than 50 years.

The Ortners and their friends were not weekend preservationists. Everett wrote to David Rockefeller asking the head of Chase Manhattan bank why he wouldn’t give mortgages on brownstones. That led to a meeting with the head of Chase’s mortgage department, which eventually led to Chase committing $100 million in community mortgage lending. They went to the senior mortgage officers of other banks, inviting them to informal get-togethers hosted by owners in their renovated brownstones. These relationships loosened the purse strings and helped other potential homeowners buy.

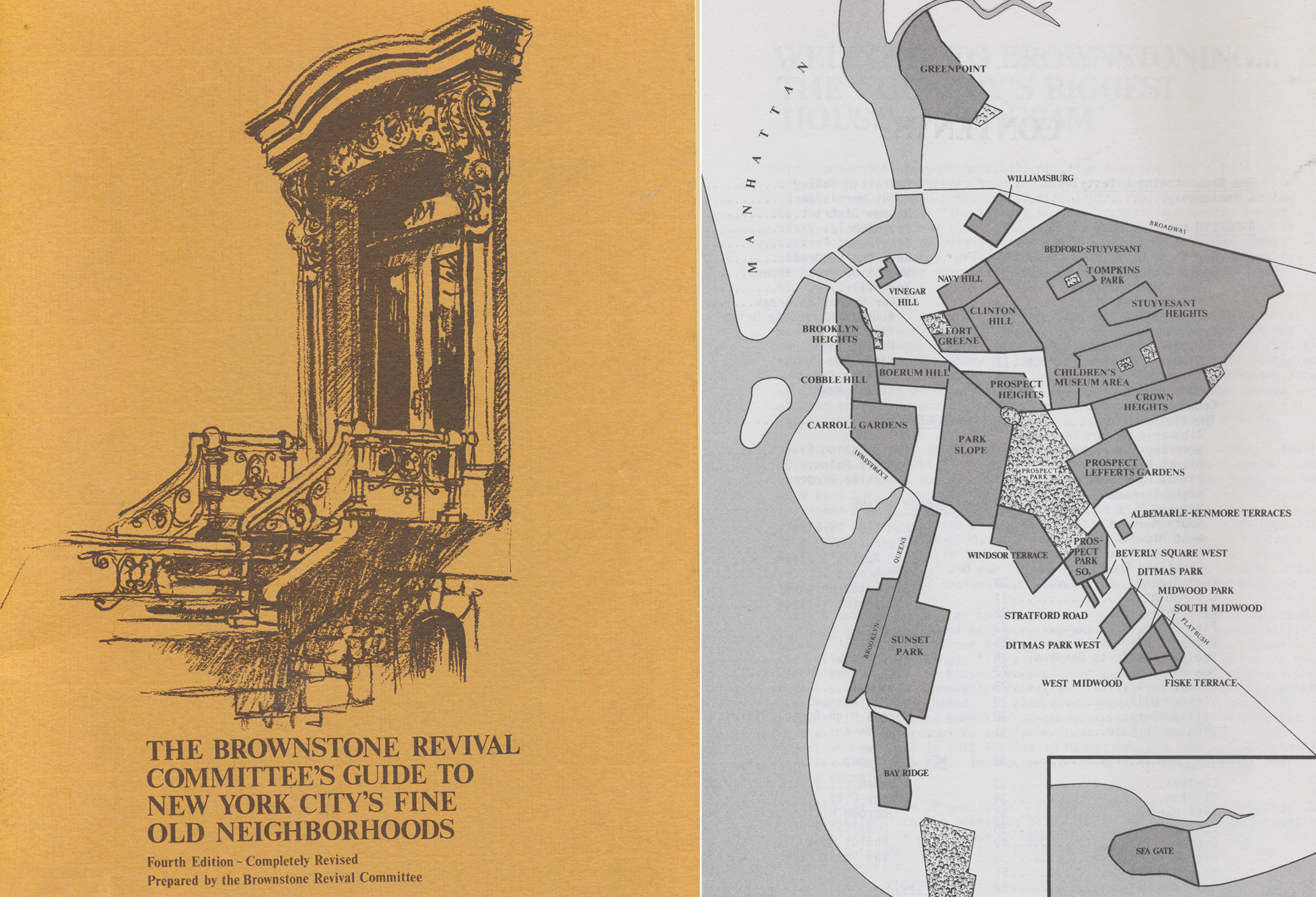

These Park Slopers founded the Brownstone Revival Committee in 1968, dedicated to the restoration and revitalization of brownstone neighborhoods. They found that there were a growing number of people who loved their Victorian row houses and wanted to renovate and restore them back to their original glory. Most of the houses were built as middle- and upper-middle-class homes and 100 years later were still affordable to new middle-class buyers. A schoolteacher, an accountant, or a postal worker could afford to buy a house in Park Slope.

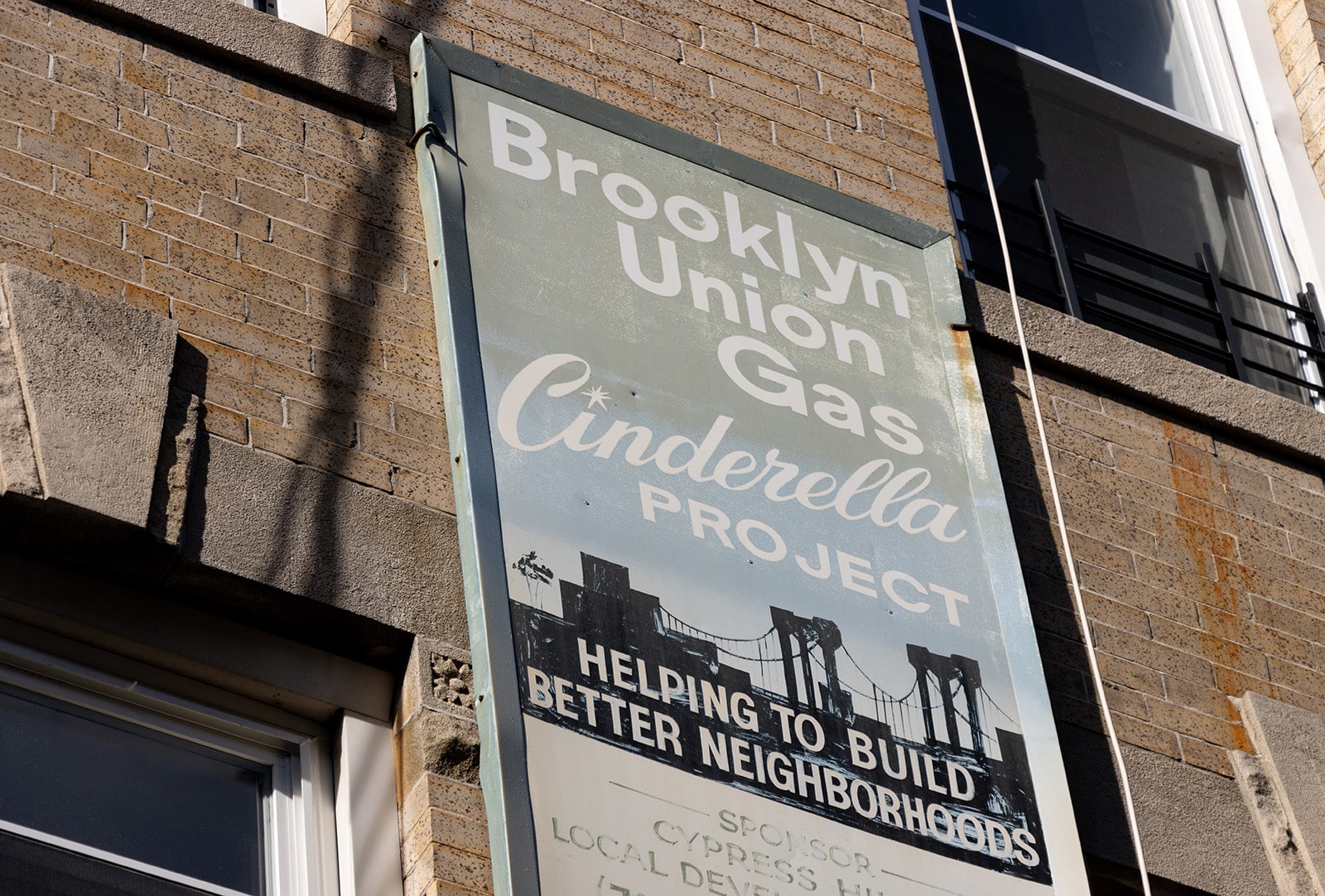

The Brownstone Revival Committee approached Brooklyn Union Gas seeking support. Brooklyn’s largest company saw the advantage in joining in. New homeowners meant new customers; it was a win-win. They were persuaded to buy an empty house and turn it into a modern showcase, highlighting the possibilities for more than just Victorian renovations. A property at 211 Berkeley Place became the first of BUG’s Cinderella Projects, which continued with grants and benefits awarded to rehabilitation projects across the borough. The utility was a committed sponsor and invaluable in cutting through red tape for those in the program.

The Brownstone Revival Committee held meetings, published a newsletter called The Brownstoner, and put on conferences. The next step was to make sure that their investments and their neighborhood remained. The PSCC approached the new Landmark Preservation Commission and advocated for a Park Slope Historic District. They realized that as their neighborhood was becoming more popular and desirable, it wouldn’t be long before real estate developers started buying just to tear down and rebuild.

Because the LPC didn’t have a large staff, Evelyn Ortner and others conducted much of the research and photography needed for designation themselves. The Park Slope Historic District, which protected about a quarter of the neighborhood closest to the park, was designated in 1973. Prospect Park itself was designated in 1975. Subsequent PSCC members would advocate just as passionately to landmark more of the neighborhood, and they eventually succeeded with extensions in 2012 and 2016, protecting about a third of the neighborhood.

Robert Mackla, the Ortners, Joseph Ferris (another unsung hero), and their group were adamant in declaring that their goal was to make their neighborhood a vibrant and multicultural one. “Park Slope is one of the most decently integrated neighborhoods in the city,” Ferris told The New York Times in 1966. “We want to keep the Slope open and attractive to Negro families. This is one of the stated purposes of our organization.”

Yet as the movement grew, and the popularity of Park Slope and other Brooklyn neighborhoods grew, as did prices, the media latched onto the idea that new homeowners and renters were “urban pioneers,” which implied that they arrived in neighborhoods that had been in wait for them to “discover” them, and change them, regardless of what that meant to the communities of people who had been living there for decades. Gentrification soon became a word and an issue that is even more relevant today with so much more money in the pot.

Although their efforts made Park Slope and other neighborhoods more attractive to new buyers, recognition did not always extend to the neighborhoods of central Brooklyn. For many years, Crown Heights and Bedford Stuyvesant, which has more brownstones than any other New York neighborhood, were not considered part of brownstone Brooklyn by the press or real estate agents. These neighborhoods were still seen as too crime ridden, too low income, and too Black and brown, and were rarely considered by white potential owners.

Yet Bedford Stuyvesant had its own brownstone revival going. Many of the homes had been in families for several generations. They were purchased despite redlining, as owners worked multiple jobs and rented out floors and rooms to pay the higher mortgage rates private lenders demanded. The same advantages of city living existed in Bed Stuy – easy access to major subway lines, a sense of community, cultural organizations, block associations, and neighborhood pride.

While it was true that there was certainly poverty and its accompanying social ills, horrific slum areas, abandoned buildings, and dismal housing projects in Bed Stuy, there were also beautiful blocks with middle-class owners who were as house proud as any Park Sloper. They had less opportunity and funding, however. The creation of the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation in 1967 brought investment back to Bed Stuy, with programs for facade renovation and other home projects among its other activities.

As the brownstone movement flourished in the Heights and Park Slope, African Americans came to Bed Stuy, drawn by culture and family connections. The Brownstoners of Bedford-Stuyvesant, founded in 1978 by local homeowners, attracted like-minded people. “Come on Home to Bed Stuy” is the group’s motto.

The organization also sponsors yearly house tours (next year will be their 47th). Like the Park Slope tours, they show potential homeowners and old-house lovers alike the beauty behind the front doors. Original details have been preserved or restored, and many houses show off collections of African art and contemporary art, which perfectly complement the original details.

Similar efforts were under way in the historic communities of Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, Crown Heights, Prospect Lefferts Gardens, and Flatbush, with groups putting on house tours and other community events and working to landmark historic districts. In 1969, the Prospect Lefferts Gardens Neighborhood Association held its first house tour, designed to racially integrate the neighborhood and stop block busting. Longtime Brownstoner reader Bob Marvin and his wife, Elaine, were among those who found their dream home in PLG in the early 1970s in much the same way the Ortners and others did. They went on a house tour.

The interest in old houses was national and even global. Since many trades and suppliers were not equipped to fix or source authentic parts and features, a strong do-it-yourself community was created. House tours became places where people exchanged the names of good tradesmen and products. Old companies that still had the molds or abilities to supply products began to make those products again. New companies and trades began specializing in old-house goods. The brownstone movement became more than just a late 20th century cause. It became a national movement, an appreciation of craftsmanship and the built environment, and made historic preservation a valuable asset, no matter where one lives.

But only Brooklyn has Brooklyn brownstones. Long may they stand!

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2024 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- Check Out These Early Brownstone Revival Books for Some Renovation Inspiration

- Making a Life in Brooklyn: Carroll Gardens Brownstoners in the 1960s

- Another Look at the Ortner House

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

A really good history; thank you Suzanne!

Elaine and I are flattered to be mentioned towards the end.

BTW, until I read this I was unaware that we benefited from the $100 million in community mortgage lending that the Ortners negotiated with Chase. We got our mortgage from Chase in 1974, a time when it was unusual to get a home mortgage from a commercial bank. None of the savings banks and savings and loans that we approached would even give us an application.