Brooklyn Heights Showhouse Started as a Family Home on Doctors' Row

A Greek Revival row house selected for this year’s BHA fundraiser was home to a doctor’s family for decades and played a role in the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous.

One in from the corner, the house at 182 Clinton Street in Brooklyn Heights this month. Photo by Susan De Vries

Chosen as this year’s showhouse to benefit longstanding local nonprofit Brooklyn Heights Association, an 1840s Greek Revival row house on Clinton Street was home to a doctor’s family for decades and has an intriguing history connecting it to the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous.

While the current interior of the brick row house reflects the many renovations and changes in style since it was first constructed, the life of that family, the Burnhams, was well documented. Their doings provide a glimpse of life in late 19th and early 20th century Brooklyn Heights.

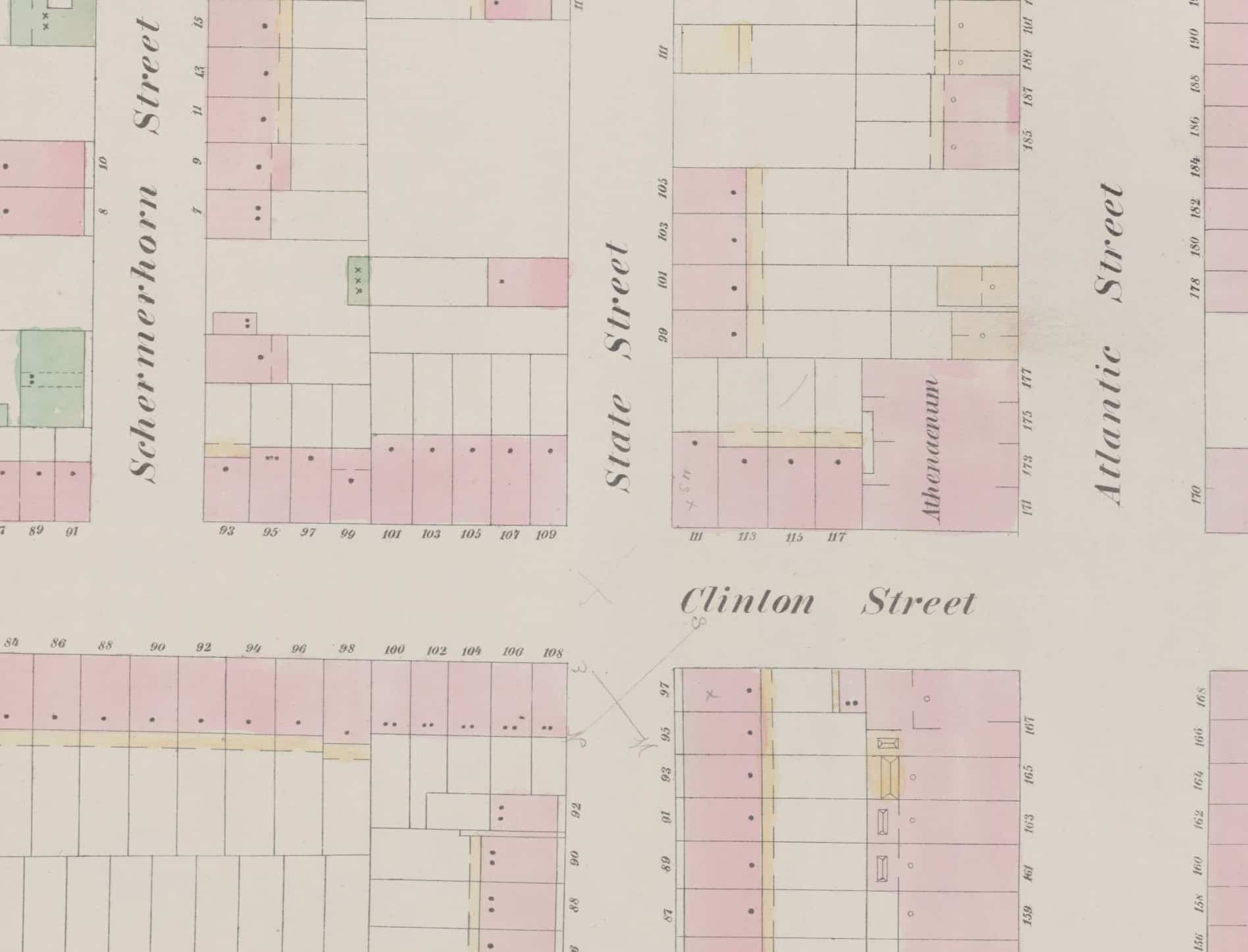

The appellation “Doctors’ Row” has been ascribed to blocks in various neighborhoods in Brooklyn across the years. In the Heights, doctors in the late 19th and early 20th centuries congregated along a stretch of Clinton Street. It was here, at No. 182, that the Burnhams made their home for decades.

Fortunately, a daughter of the family wrote about her childhood and studiously saved photographs and objects. The events of her life during her time there have also made the row house an important touchstone in the history of the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous.

The 19th Century

The history of the house begins well before the doctor’s family, in the 1840s when builders were constructing rows of brick houses across the blocks of Brooklyn Heights. The restrained Greek Revival style houses were grand but not grandiose, spacious but not massive. For single-family dwellings, they were generously sized and conveniently large enough to accommodate lodgers, as so many dwellings in the neighborhood did in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Dating to 1848, 182 Clinton Street was one of several speculative houses built by Isaac Woods on the block. Deed research by local historian Jeremy Lechtzin shows that Isaac Woods originally bought the land on which 174 to 184 Clinton Street and 121 State Street sit in 1836. Woods hung onto 182 Clinton Street, known as 106 Clinton Street before the 1870s street renumbering, as a rental property until 1853.

When originally constructed, it would have been fairly typical of its time, with a simple cornice and molded brownstone lintels. In 1880, then-owner and widow Annie Peterson raised the roofline 2.5 feet at a cost of $520. The more ornate bracketed cornice was likely added then, replacing the original cornice.

The brownstone lintels survived longer; they were still in place in the early 1930s, old photos show. By the time of the circa 1940 tax photo, they had been shaved down to the simple lintels in place today.

Owner Annie Peterson’s raising of the roofline not only added an au courant stylistic flourish to the house, but it also likely gave a bit more headroom on the top floor. Like other owners before her, Annie took in boarders, advertising “lovely, large front and back rooms” and a “first class location.”

In 1880, the year of the alteration, the census shows she was sharing her home with her daughter and son-in-law, married boarders from Germany, and two servants. By 1884, Dr. Clark Burnham was in residence; he started as a renter and eventually bought the property.

Doctors’ Row

When Dr. Burnham moved to Clinton Street, he was just a few years from his 1881 graduation from the Hahnemann Medical Collage in Philadelphia. A surgeon and gynecologist, the Pennsylvania-born doctor moved to Brooklyn, originally living near Prospect Park, according to family lore, before making the move to Brooklyn Heights.

While the 1880 census records already show a number of doctors in residence in the surrounding blocks, by 1892 the Brooklyn Daily Eagle would declare Clinton Street “Doctors’ Row.” An estimated 48 doctors lived on the thoroughfare between Pierrepont and 4th streets. The paper counted 12 alone living between Schermerhorn and State streets that year and noted Dr. Clark Burnham among them.

The concentration of medical professionals along the thoroughfare perhaps explains why Dr. Burnham would stay in residence on Clinton Street through the next several decades. Close to Atlantic Avenue and just a block from a stylish apartment house that was constructed in 1881, the stretch wasn’t as grand and exclusive as streets to the north, but it had easy access to transportation and medical establishments like the Long Island College Hospital. The location also provided a young doctor with access to the wealthier clientele of Brooklyn Heights.

In 1888, still in residence at 182 Clinton Street, Dr. Burnham married local girl Matilda Spelman. The couple raised their family on Clinton Street and retained the property until the 1930s.

The Burnham Family

When Dr. Burnham married Matilda Spelman, he was marrying into a family already well established in Brooklyn Heights. The daughter of dry-goods merchant William Chapman Spelman and wife Sarah Hoyt Spelman, Matilda grew up at 121 Willow Street (demolished in the 1920s) near Clark Street. Born in 1864, she attended local schools and graduated from Miss Whitcomb’s Seminary in 1882. Located on Atlantic Avenue near Clinton Street, it offered lessons in French, German, art history and “full collegiate and special courses of study.”

Oration was likely taught as well, with readings a significant part of the regular commencement ceremonies. Matilda is mentioned as giving readings in some newspaper accounts of such ceremonies. In 1881, a portion of her “most amusing” schoolgirl essay on music was printed in The Brooklyn Union.

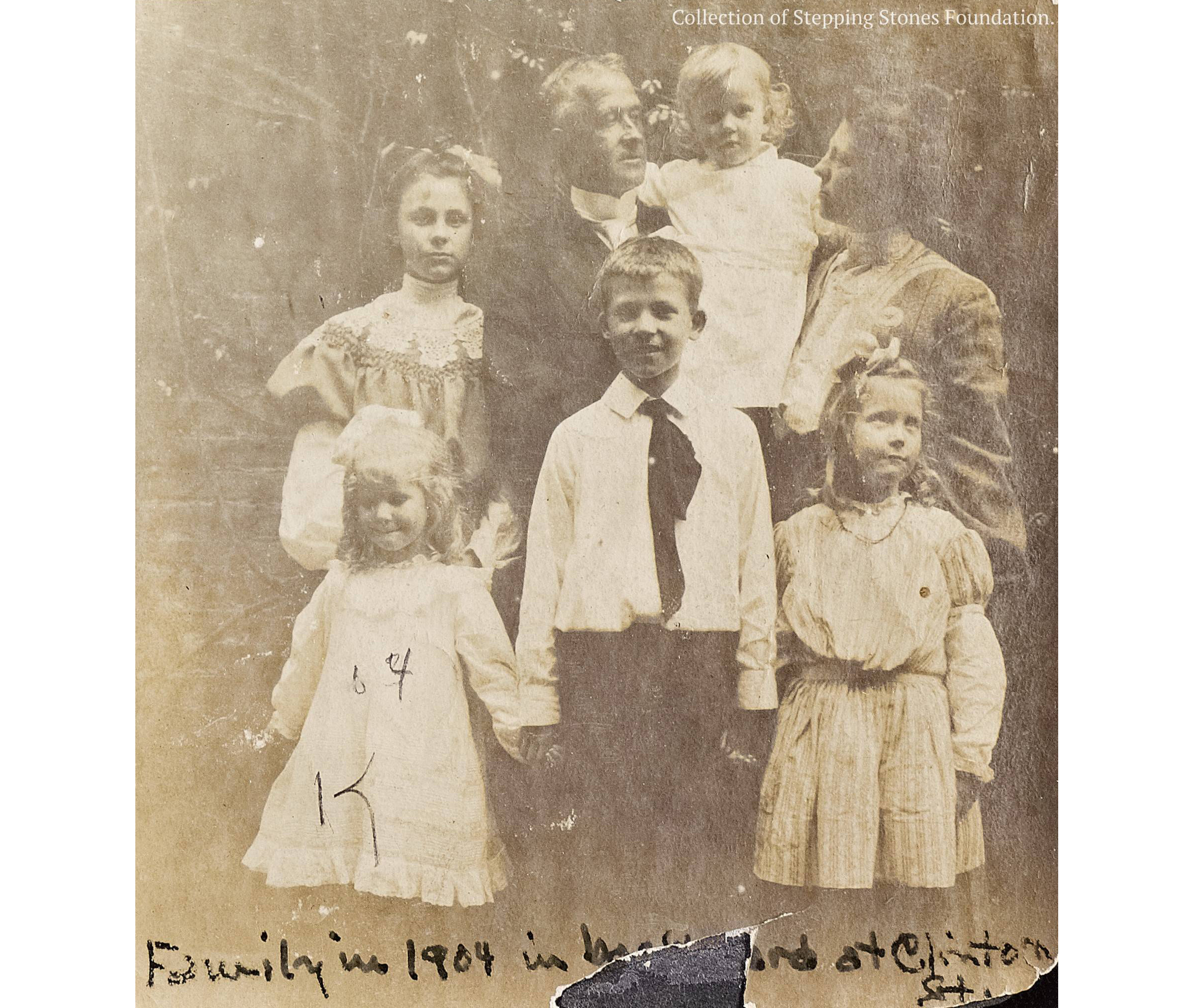

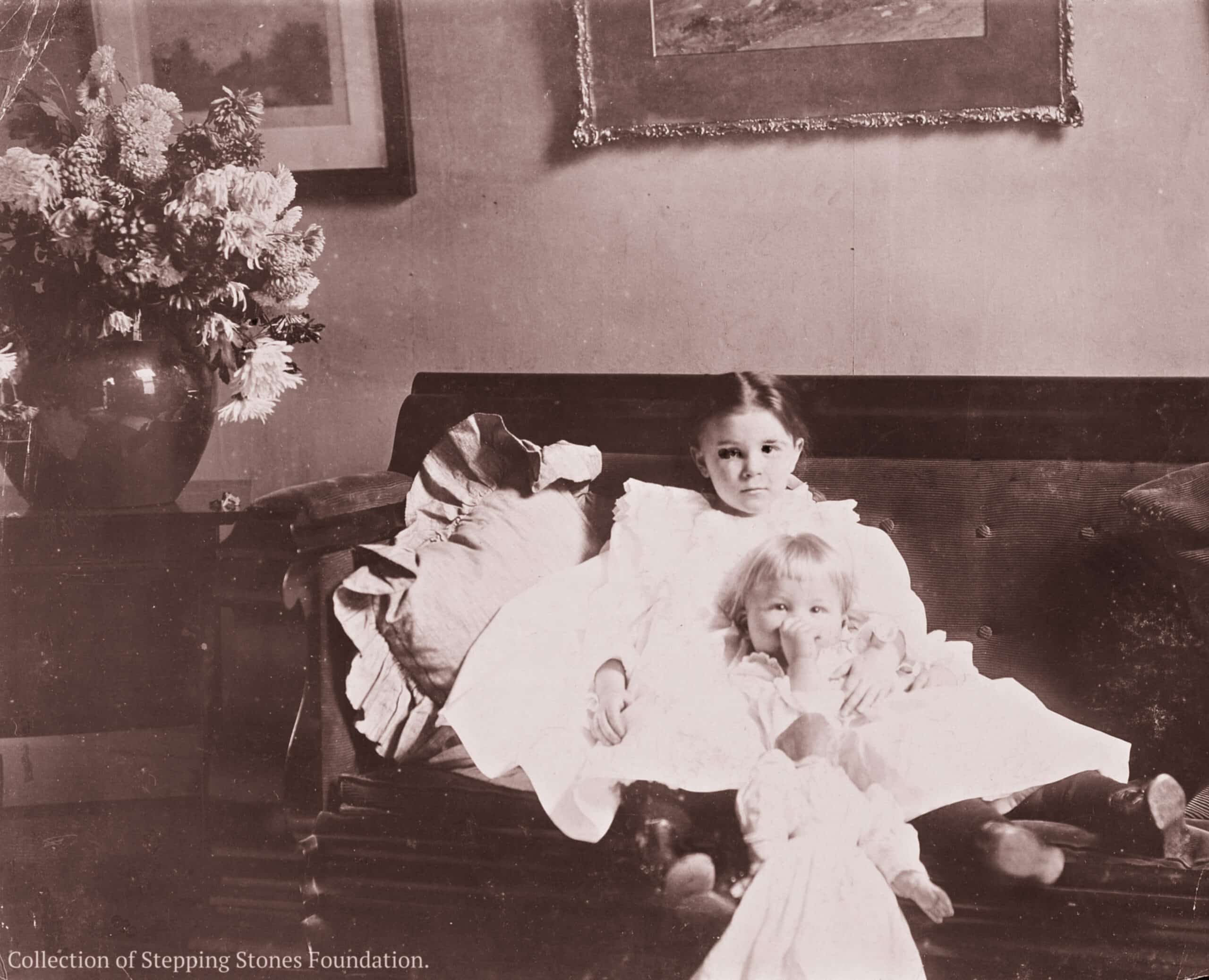

After marriage, and amidst the birth of six children between 1891 and 1906, Matilda seems to have immersed herself in the clubs, charitable endeavors, and activities of a young married woman of her set. She had a flair for the dramatic and, particularly once the children had reached school age, she appears frequently in local papers as taking part in readings, plays, and charity programs in the neighborhood.

Records of the Brooklyn Woman’s Club, established in 1869, show Matilda joined in 1913 and was active in the drama department. Both she and Clark were members of the Woodman Choral Union and attended the Church of the New Jerusalem, a Swedenborgian church. Known after 1929 as the Church of the Neighbor, it stood on Clark Street at the corner of Monroe Place, and the basement of the church held the Neighborhood Club, a popular gathering and performance space used by local civic and arts groups. The dwindling congregation sold the building in 1960, and it was demolished as part of the Cadman Plaza project.

The club space, which included a stage, hosted productions by the active amateur theater circle of Brooklyn Heights, with Matilda a frequent participant. She served as director of the Neighborhood Players for a few years and also appeared in plays produced by the Brooklyn Heights Players. She had roles in works by Ibsen, Christopher Morley, and Booth Tarkington, earning some fine reviews. In 1927, the Brooklyn Daily Times gave her a nod as “one of the most finished character actresses in Brooklyn.”

Particularly when her children were young, her social life was possible only with household help. Census records show the family typically had two or three live-in servants between at least 1892 and 1915. One of those, Irish immigrant Margaret “Maggie” Fay, remained with the family for 25 years.

Memories of Maggie and the days of the Burnham family at 182 Clinton Street were recorded by Lois Burnham Wilson, the oldest child of Clark and Matilda, in private writings and published accounts. Of the five children who survived to adulthood, she remained in the house the longest, and it is her story that ties the house to the early years of Alcoholics Anonymous with her marriage to and support of co-founder Bill Wilson.

In her memoir, “Lois Remembers,” published in 1979, she describes Maggie Fay as a “wonderful cook and quite a philosopher.” Lois also mentions coachman Edward Lord and his mother, Betty, who took care of the Burnham children when they were young. Elizabeth “Betty” Lord, born into slavery, according to Lois, appears at 182 Clinton Street in just one year of the census. In 1900 she is recorded as born in North Carolina in 1852, widowed with one child, and a servant within the Burnham household. Betty was still in the household in 1904 when a robbery at 182 Clinton Street made the news. A man, faking injury to wait for the doctor, managed to slip by the unsuspecting Betty and head upstairs to nab some family jewelry.

The House Interior

Patients appearing at the brick row house would not have been an unusual occurrence as it was not only filled with a large family and servants but also accommodated Dr. Burnham’s medical practice. Pages of typewritten notes by Lois about her childhood include her memories of the layout of 182 Clinton Street.

As expected in a house of this era, the dining room and kitchen were on the garden level. A butler’s pantry later held a telephone for patient calls. The main level of the house, rather than being given over to impressive parlors, had a waiting room at the front and a consulting room and office at the rear for Dr. Burnham.

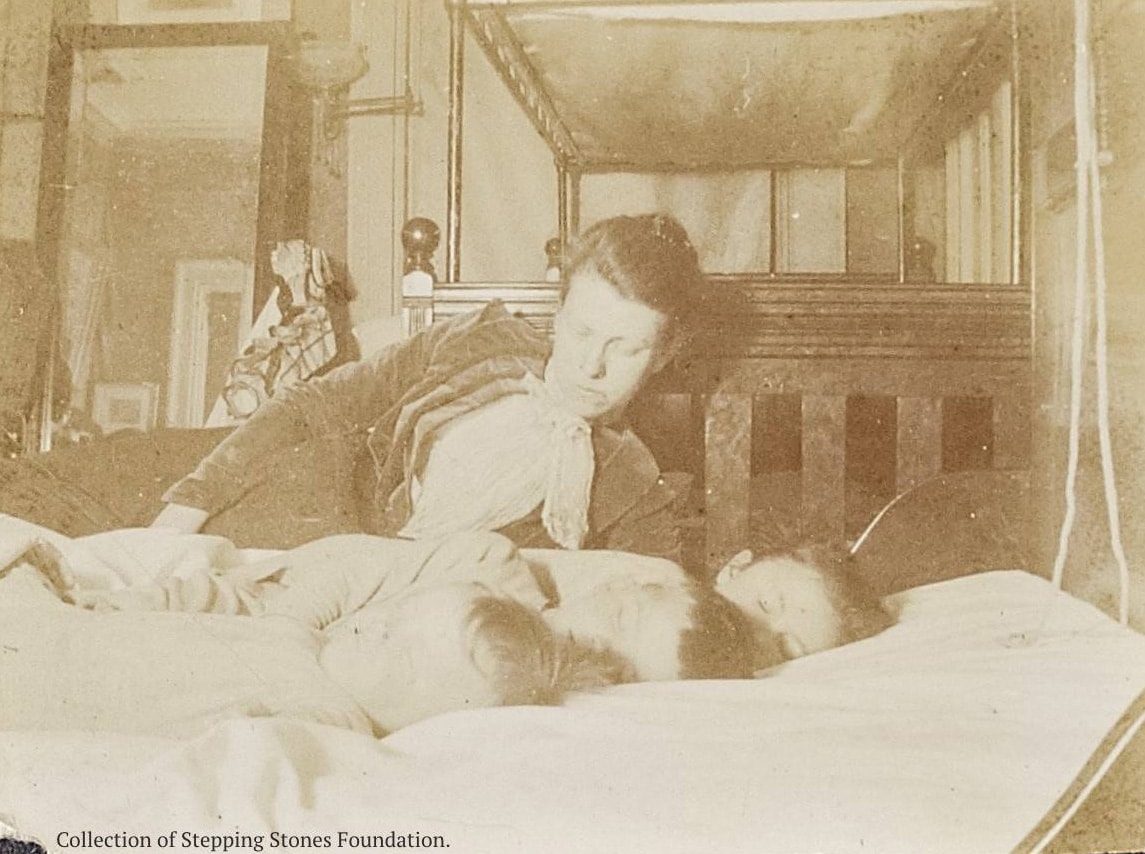

On the second floor, a family sitting room faced the street and a bedroom faced the rear garden. While it was the parental bedroom, Lois recalls she and her siblings, including Rogers, Barbara, Katharine, Lyman, and Matilda, slept in the room with their parents when they were young. A tiered crib allowed multiple children to sleep next to their parents’ bed until they were old enough to move to rooms upstairs. The top floor of the house had enough space for the live-in servants and children.

Servants used a privy in the rear yard, while the family had one bathroom. Lois recalled it as wood filled, with wood floors, wainscoting, and toilet tank, while the tub was copper.

A few family photographs provide glimpses of the interior and show the expected heavy furniture of the period as well as art-filled walls in the family sitting room. Some of the paintings were likely by Ben Foster, a family friend known for his landscapes of New England.

Deeds show the Burnhams remained renters at 182 Clinton Street until they purchased it in 1908. However, in addition to staff salaries, household costs, carriage and later motor car expenses, and schooling for the children, they also had the expenses for running a second household. Beginning in the 1890s they began summering in Manchester, Vermont, where Matilda’s family had a vacation home. Eventually the family purchased their own “camp” in Vermont and divided the year between 182 Clinton Street and their rural retreat.

The 20th Century

For some, the house at 182 Clinton Street is a place of significance because of the events that took place there in the 1930s while Lois and Bill Wilson struggled to hang onto the family home.

In the 1920s the house was still filled with family, with census records showing several of the adult children still in residence. Matilda Burnham died in 1930, noted in her obituary for her talents as “a reader and monologist.” Clark Burnham remarried in 1933 and left the house, moving to Westchester and leaving the Wilsons responsible for the mortgage on 182 Clinton Street.

That mortgage was substantial, according to Lois’ accounts, and neither she nor Bill had consistent employment. Bill had been sliding ever downward into alcoholism and the early 1930s marked some of the worst of his drinking. It was a 1934 conversation at the kitchen table at 182 Clinton Street with his old friend and drinking buddy Ebby Thacher, who had found a path towards sobriety with the Oxford Group, that pushed Bill closer to facing his addiction. He entered the Charles B. Towns Hospital in New York, an early treatment center, for the final time. A timely meeting in Akron, Ohio, with Dr. Bob Smith, a struggling alcoholic, led to what is considered the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous on June 10, 1935.

When Bill returned to Brooklyn, some of the work of the young movement took place at 182 Clinton Street. Alcoholics came and went from the house and attended meetings; many became temporary boarders. The first book outlining the A.A. principles and the 12 Steps, known as the “Big Book,” was published in March of 1939 while the couple was still living in the house. This era of history of the residence has been well covered in Lois’ autobiography as well as subsequent biographies of both Wilsons.

That spring would mark the end of the Burnham family’s time in the house. A deed shows that Dr. Burnham sold the house in 1935 to the Birdseye Realty Corp. and there was a $12,500 mortgage on the property. In her biography Lois recalls her father receiving a “mere $200 for the deed.” Dr. Burnham sold the Vermont property the same year, and he died in 1936. The Wilsons were able to stay in residence on Clinton Street until April of 1939 when the new owners removed the tenants and put the house on the market.

In August of 1939, a few months after the couple moved, a certificate of occupancy was issued for the house as a three-family with a doctor’s office on the garden level. Visible in the historic tax photo is signage near the garden level entrance, likely for that office. In 1956, the doctor’s office was eliminated in favor of another rental unit, and in 1992 the house was converted back into a single-family.

Fortunately, when the Wilsons left 182 Clinton Street they managed to pack away family furniture, objects, and photographs. Those items stayed in storage for the next two years while they depended on the kindness of friends and the members of their fledgling group for places to live. In 1941 they settled in Westchester, and their home, Stepping Stones, is now a museum where visitors can learn more about the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous and Lois’ work in cofounding Al-Anon. Visitors can also get a look at Burnham family furniture moved from 182 Clinton Street, including an ornate hall stand, a bed that once stood in the second floor bedroom, and the famous kitchen table. In addition to maintaining the house and offering tours and public programs, The Stepping Stones Foundation has an extensive online archive relating to the lives of the Wilsons and their work.

Since the Wilsons’ time, the house has seen a number of occupants and updates. A few 19th century elements remain intact, including a black marble mantel in the front parlor and a newel post and stair.

The interior is getting a new look as the latest Brooklyn Heights Designer Showhouse and opens to the public on Friday, September 27. It will run through November 3 and proceeds will support the work of the Brooklyn Heights Association. Tickets can be purchased online.

Related Stories

- A Lost Daughter and the Women of a Brooklyn Heights Greek Revival Showpiece

- The Lore of 13 Pineapple Street, One of Brooklyn Heights’ Historic Wood Frame Houses

- Inside One of Brooklyn Heights’ Oldest Houses, 24 Middagh, and Its Mysterious Past

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment