Albert Korber and the Business of the Artful Home

Prominent 19th century Brooklyn designer Albert Korber decorated Park Slope’s swank Montauk Club and was known for reimagining older homes.

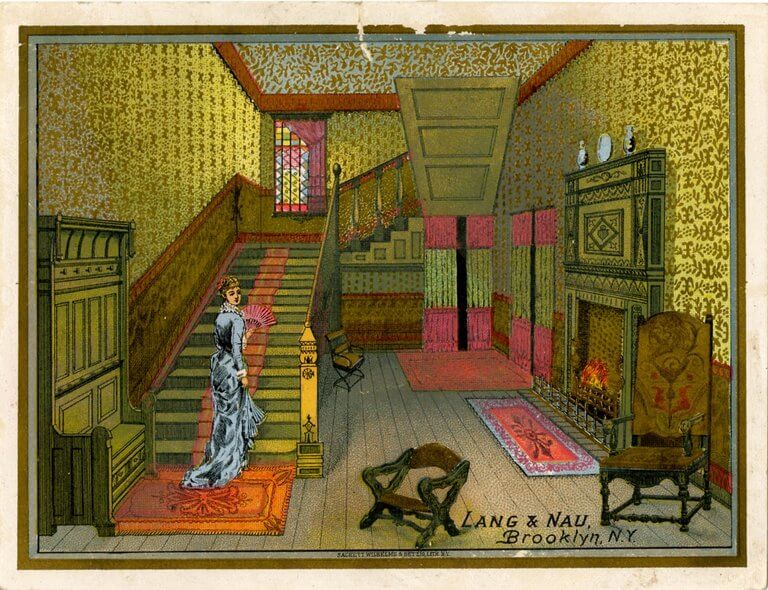

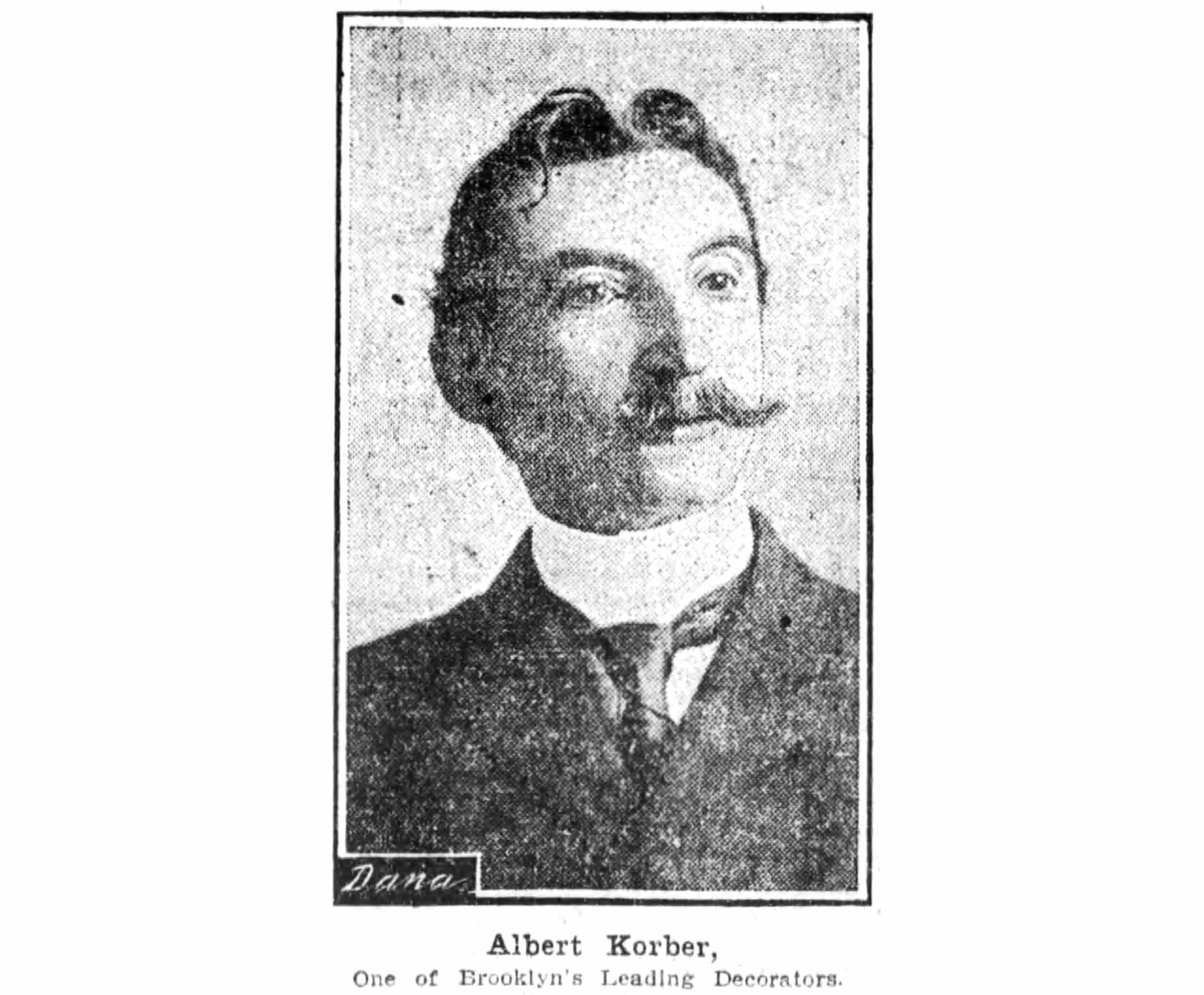

Brooklyn decorator Albert Korber in 1908. Image via Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Wallpaper by the American Wall Paper Manufactures’ Association produced circa 1879-1887. Image via Cooper Hewitt

From the first time a caveman or woman drew pictures on the walls and brought some flowers into the cave to brighten up the place, we’ve been decorating where we live. Today the interior design industry is booming more than ever before. The trade and niche magazines show us the best of the best, usually with designer names and expensive furnishings and materials. There are all kinds of decorator blogs and websites and there’s Pinterest, Instagram, and television. Most major cities have a “decorator district” with showrooms and businesses of all kinds catering “to the trade,” and some people can’t imagine furnishing their homes without the aid of an interior decorator or designer.

Who would imagine that a television network that only broadcasts design, renovation, or house-hunting shows would host many of the tastemakers of the day and be lucrative and popular enough to inspire other shows and even other networks? The programs have made some of their hosts household names and multi-million-dollar celebrities. We wouldn’t have “open plan” houses or see shiplap sold in Home Depot if it weren’t for HGTV. Even though most people realize that the “reality” in most of these shows is contrived, we still love the reveal.

The interest in home decoration goes back centuries throughout the world, but in the United States, it really came into its own in the latter half of the 19th century. The period after the Civil War was a perfect storm of many different societal changes. The greatest of these were the advances in technology, mass production and products, and the growth of the middle class, who eagerly bought whatever they could.

Throughout history, the rich have always been able to concern themselves with design and decor. They could afford to hire tastemakers who advised them, craftspeople who executed the designs, and lots of servants to take care of it all. They had the best of the best and the latest style, be it for a townhouse, palazzo, or country estate.

The Industrial Revolution brings “artistic homes” to the middle class

By the 1830s, the Industrial Revolution was in full swing in England. Great advances were made in textile manufacture, the use of steam power, and the mechanized production of steel. These advances influenced just about everything, creating a large population of poor factory workers, and a growing middle class. It also affected how and where people lived, as factory work drew a once rural population into the rapidly growing industrial cities and crowded slums.

This same industrialization came to North America a few years later and repeated itself here. The Victorian Age lasted through the rule of England’s Queen Victoria, from 1837 to 1901, and although we fought a revolution to get away from the dictates of royalty, the term “Victorian” encompasses all Western design and architecture from this time period – 64 years that forever shaped how we live.

War always brings new technology with it. Efforts to find ways to preserve food for the troops during the Civil War produced the myriad forms of the canned goods of today. In the 20th century, during World War II, research into microwave technology for weaponry made the $60 microwave on your kitchen counter possible. The list goes on and on.

America came out of the Civil War with new ways of mechanizing techniques that had been done individually, and expensively, by hand. Just as the pneumatic drill transformed stone carving on our brownstone facades, advances in printing, paint, and textile manufacturing, to name just three, made more goods available for the middle class.

The Aesthetic Movement was the perfect name for a design philosophy in which every surface and object in a room was chosen as much for its individual and collective beauty as for its function. And although the wealthy could afford sterling silver, name brand furnishings, and hand blocked wall coverings, the middle class could buy tasteful knock-offs made from lesser materials and still be proud of their homes.

The wealth created during the Golden Age of the latter quarter of the 19th century paid for grand mansions and town and country homes where more was certainly more. Elegant velvets and brocades covered the bespoke furniture and hung from drapery rods. The walls were covered with patterned wallpapers in florals, geometric shapes, stripes, and the patterns of ornament from the exotic East and the Orient. Every room, every hallway was covered with wallpaper, some of it quite loud and complex. Paint could now be mixed with new and more stable colors. The possibilities were endless.

So, who told these people – rich and not so rich — what was fashionable, must have, or must avoid? The tastemakers and decorators of their day. At this period, all of them were men, something that wouldn’t change until the 20th century. So, who was the Billy Baldwin, Tony Duquette, or Albert Hadley of the time? Another Albert – Albert Korber.

Plum commissions and updating passé dwellings

Late 19th century Brooklyn had many different men vying for decorating jobs for Brooklyn’s up and coming and wealthy set. Albert Korber was one of the more prolific of this group. The son of German immigrants, he was born in New York City in 1847. He moved to Brooklyn at the age of 15, trained as an architect, and also advertised himself as a decorator. By the age of 18, he was an accomplished gilder, then he established his first shop, specializing in picture frames and molding.

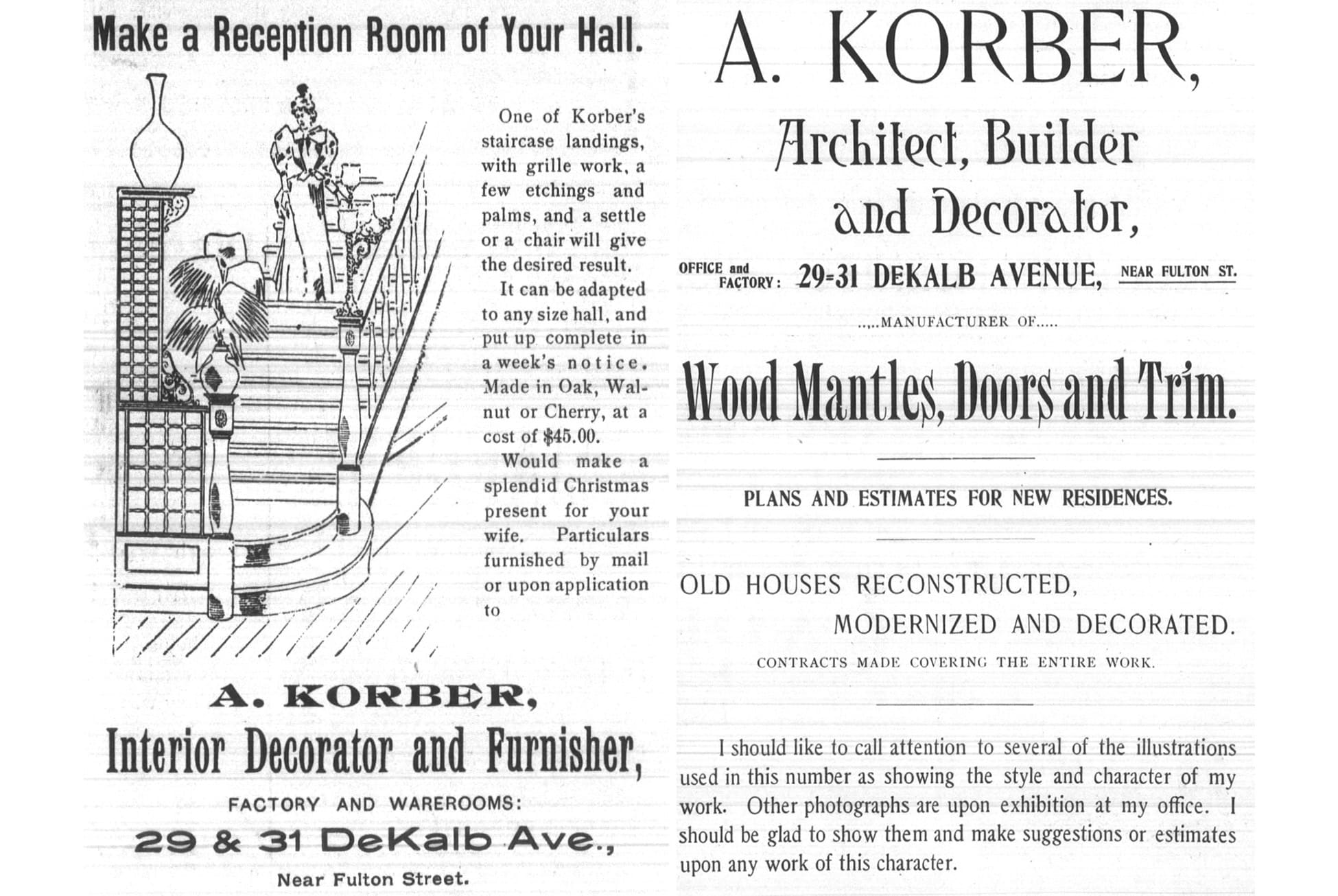

His first showroom was at 155 Montague Street, near Clinton Street. There he displayed not only his frames but his furniture, moldings, fireplace mantels, and more, which were manufactured in his Adams Street factory. His showroom also gave homeowners a glimpse of what he could offer as his total package, with wall coverings, painted ceilings, fabrics, stained glass to order, and more.

In 1889, at the age of 42, he was doing really well, his name and work described with lavish reports of the decor he created for his wealthy clients in townhouses in Brooklyn Heights, Park Slope, and elsewhere. Had there been color photography and lush interior magazine spreads of his projects, it would have rivaled anything done today in House Beautiful or Elle Decor. Instead, reporters wrote long and very descriptive pieces about every aspect of the decor. Not a single detail was missed.

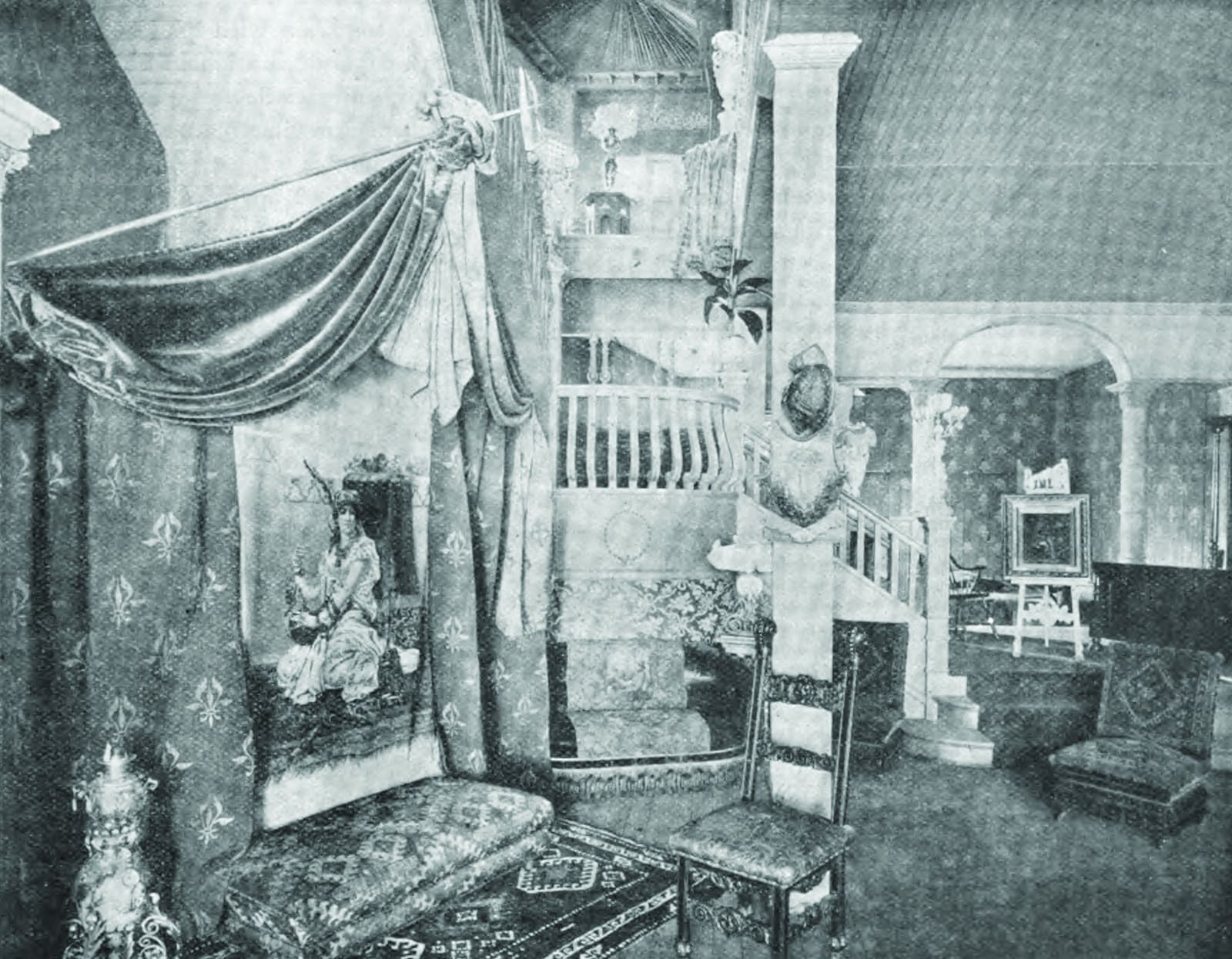

He was able to carve a niche for himself as someone who could take the parlor floor hallway and stair of an upper middle class brownstone and make it what he called a “grand reception room.” Upscale row houses of this period were ornate already; most had decorative newel posts and stairways, mirrored hall trees and benches, and perhaps some gingerbread ornamentation.

Korber liked to place a platform at the bottom of the stairway, remove the moldings and cornices in the hall, and install a cove ceiling. He would also remove the doors in the hall and leave or install ornate gingerbread trim. Both treatments would effect a taller, wider space with light passing through the ornamentation. Mirrors were placed strategically, and the surfaces were painted in rich colors.

The addition of statuary and rich draperies made the hallway a reception room unto itself, before guests moved into the front parlor, which had traditionally been the chief room for social functions. The lady of the house could descend the stairs and greet guests from the new raised platform. It was all very posh. Who knows how many hallways he changed over the course of his career, especially in Park Slope, where he was living at the time.

Korber received great acclaim as the interior designer of Francis Kimball’s Montauk Club in Park Slope. The club opened in 1891. Korber’s home was around the corner on Lincoln Place at the time, so he was on site often supervising the interior finishing and decoration. The building has five stories and several ornate gathering rooms, game rooms, lounges, a grand dining room, and guest rooms.

The interior decor cost the club almost $30,000, more than enough money to build an entire row of brownstones in the same neighborhood. Deep pockets – every decorator’s dream, then and now. Korber gave the club what was becoming his signature look – rich fabrics for heavy draperies and portieres, antique silver and gold burnished gilded ceilings and walls, and rich upholstery.

Another project around the same time was the decoration of two rooms in the new 23rd Regiment Armory on the corner of Bedford and Atlantic avenues. In 1894 he designed the Company “F” and “D” rooms in the armory, rooms that were designed to impress the officers and the public at large.

An illustration in the society magazine “Brooklyn Life” shows a woman sitting demurely in an ornately carved window seat. A lion skin rug is at her feet, a patterned drapery is artfully gathered near the top of the window, revealing stained and beveled glass windows. The result is a Medieval look, something that complements the castle-fortress architecture of the armory. The 23rd Regiment was Brooklyn’s “rich boy’s regiment,” in competition with Manhattan’s Park Avenue Armory. These rooms would not generally have admitted women. but were used for meetings and social functions where ladies would then be welcomed.

A commission from a captain of industry

Wealthy clients can be the best clients. Korber decorated Standard Oil executive E.T. Bedford’s home at 181 Clinton Avenue (later demolished) in Clinton Hill. Bedford was so pleased, he had Korber design a summer home for his son Frederick in Green’s Farms in Connecticut (also gone). The description of the house in the Brooklyn Citizen noted that it had 14 rooms and was in the style of an English manor. It’s unclear if Korber designed the house itself, or just the decor. Montrose Morris, whose name is familiar in Brooklyn architecture of that period, designed both the Clinton Hill house and E.T. Bedford Senior’s enormous manor house in Green’s Farms.

Korber stayed in the game as the 19th century ended and a new century began. In 1902 he moved his Dekalb Avenue showroom across the street to an existing three-story building that he redesigned as a Medieval castle. It had a crenellated roofline and was covered in cast iron. Inside, the floors were covered in layers of Oriental rugs, and every surface was covered with decorative elements that were available for sale. It was said that he could “take an old house, reconstruct and furnish it, and modernize it so that it would be hardly recognizable. His architectural alteration work is of the best kind.”

He was acclaimed as one of Brooklyn’s leading decorators but he had many competitors. The Brooklyn Eagle published an extensive six page spread in the Saturday, March 21, 1908 edition. It featured articles and advertisements for some of the borough’s best known decorators, contractors, and shops. Korber was one of them. Most of the storefronts and offices were downtown, but there were also advertisements for decorators in Flatbush, Bedford, Clinton Hill, and Williamsburg. Korber advertised in the papers often — sometimes just a paragraph or two, other times featuring a room or furniture of his design.

Albert Korber also had a rich personal life. He married first generation German-American Gesiene Katherine Van Campen in 1885 and the couple had four children, three boys and a girl. The oldest boy, Otto, went into business with his father. The Korber offices moved around a lot. When his career began, his showroom and offices were on Montague Street. Over the course of his career, he moved his showroom to Hanson Place, then two different showrooms on Lafayette Avenue near the new Brooklyn Academy of Music. The family lived on Lincoln Place in Park Slope and later on Caton Street in suburban Flatbush.

His life and career were not always smooth sailing. His house on Lincoln Place in Park Slope was burglarized in March 1906. Thieves scaled his fence, jimmied his rear door and made away with silverware and crystal. They stuffed the loot into an alligator skin bag, but on their exit they were afraid of being caught and left the bag and the goods in the back yard, to be discovered by Albert. Another homeowner on nearby St. Johns Place was also burglarized, but the thieves made away with similar goods.

In 1914, a fire destroyed his entire inventory, as well as the items he stored for clients while they were away for the summer. The fire started in the basement of 44-46 Lafayette Avenue. It was quite a serious blaze and at one point threatened to spread to the adjoining buildings, but firefighters were able to contain it. Korber, fortunately, was fully insured. The fire caused $5,000 worth of damage, a sum that would be around $160,000 now.

Albert and his son Otto took a business trip to Havana in Cuba in April in 1918. While there, Korber suffered a fatal heart attack and died soon after. He had been in good health, making his sudden death even more unexpected. Korber was 70 years old. His body was shipped home to Brooklyn for his funeral. The family were members of the First Reformed Church on 7th Avenue and Carroll Street, where he had been a member and a deacon for 28 years and had recently been made an elder. He was buried in the family plot at Green-Wood. Gesiene passed away in 1922.

Albert Korber left a world that would clamor for interior design to this day. One wonders what he would have thought about the trends of the mid and late 20th century, especially Modernism when less was preferable to more and ornament was no longer in fashion. Had he been born 100 some years later, he too may have had his own tv show! Instead of open plan, he would be decorating hallways and parlors with lavish details, rich colors, antiqued woodwork and furniture, and more, much, much more.

Related Stories

- From Practical to Ornamental: The History of Dressing Windows

- History Underfoot: Flooring in the 19th Century Home

- A Brief History of Decorative Painting in Brooklyn and Beyond

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment